This is the ninth post of Henryk Sienkiewicz’s

historical novel, Quo Vadis.

You can find Post #1 here.

Post #2 here.

Post #3 here.

Post #4 here.

Post #5 here.

Post #6 here.

Post #7 here.

Post #8 here.

Chapters 57 thru 63

Summary

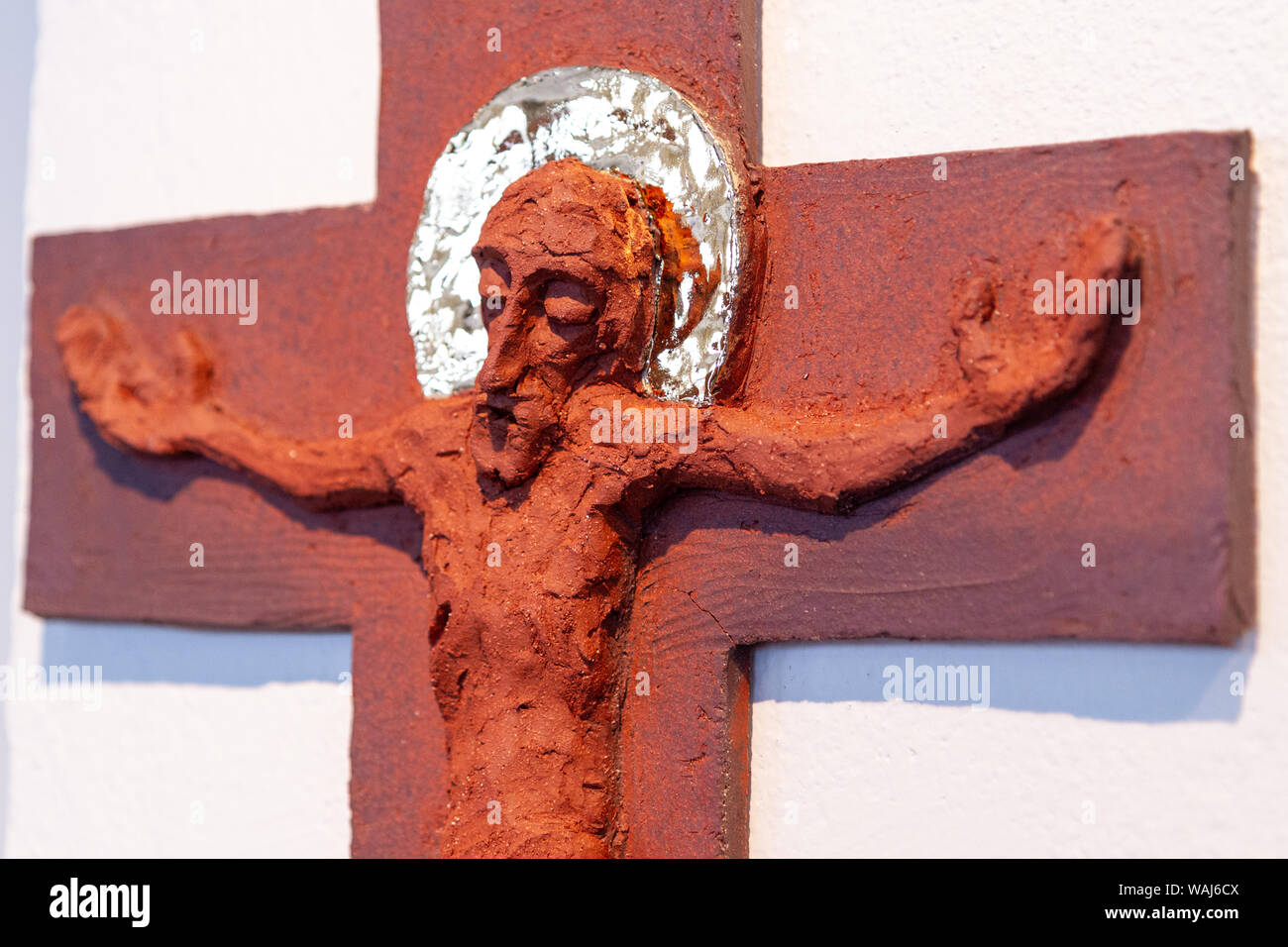

The games are interrupted by three days of rain and hail. Once they resume, Nero wants to arm Christians to fight each other to the death in the arena. The Christians refuse, throw their weapons to the ground, and kneel in prayer. Nero is forced to put an end to them by having real gladiators come in and slaughter the Christians as they passively kneel. Then Nero, inspired to exceed all past games, creates enactments of mythic and historic stories where the Christians will be raped and killed per the legends. Another spectacle put on in the arena is real crucifixions, and so Christians are nailed to crosses and lifted up, the arena filled with so many crosses it looks like a forest with the audience enjoying the slow deaths of the crucified. One such Christian is the old man Crispus, preaching the wrath of God as he is nailed and dies on the cross. The cross on which Crispus is nailed stood opposite the emperor’s podium, and Crispus and Nero faces look on each other. Crispus in his dying breath denounces Nero.

Chilo, trying to leave the games, tries to persuade Nero to leave for Greece, but Nero says not until after the games are over. Chilo insists he will no longer attend the games, but Nero stipulates that he be forced to sit next to him. Chilo feels that death is coming for him through the vengeance of the Christian God. Petronius says that the Christians in their passive deaths are actually arming and with patience will bring down Rome. Tigellinus says that this is insane.

Petronius believes that Vinicius is devising a new plan to free Lygia, but Vinicuis has lost hope. Still Vinicius decides to try to enter the new prison, just to see Lygia. Dressed as a slave the guards do not recognize him and he goes in. The prison is vast and he hears the groans of all those infected with fever. Deep in the dungeons he finally finds Lygia and Ursus. Lygia, asleep on the floor, is emaciated. He kneels by her and she awakes. She is weak but grateful to see her beloved. He tells her Christ will save them, but she believes she will die, either in the arena or in prison.

For three nights Vinicius similarly comes to the prison to be with Lygia. They talk about how they will love and live with each other beyond the grave. Petronius is astonished that Vinicius is at peace with the situation. Petronius informs him that the Christians will be human torches for Nero’s garden the next day. Vinicius again dresses as a slave and heads over to the prison. He gets there in time to see Christians being led out to go to Nero’s garden. Scanning their faces he does not find Lygia or Ursus, but he does notice Glaucus.

The Roman people have grown tired of the games, and

Nero and Tigellinus are hoping with the last of the Christians to bring the

spectacle to an end. In Nero’s garden,

Christians are tied to poles and plastered with pitch. At a given command, a slave beneath each pole

sets fire to a pile of straw. The fire

climbs the pole and ignites the pitch.

As the fire climbs the poles and up the bodies of the Christians,

screams can be heard, smell of burnt flesh can be smelled, and the garden is as

bright as day. Chilo is forced to attend

with Caesar, and is horrified at the distorted burning bodies, some still in

agony, some frozen in a death gaze. As

Nero’s entourage stroll through the garden they come to the pole where Glaucus is

strapped. Chilo lets out a cry upon

recognizing him. Nero laughs at the

shock he sees in Chilo’s face. Chilo

begs Glaucus to forgive him, and Glaucus does before he dies. Chilo drops to the ground in tears and the

Romans wonder what is happening to him.

Chilo gets up and pointing a finger at Nero and in a loud voice screams

that Nero had been responsible for the fire.

The Roman people within earshot believe him and question why the need

for the murderous games. In the chaos,

Chilo wanders away and comes across Paul the Apostle. Chilo makes a confession and Paul baptizes

him into Christianity. Tigellinus finds

Chilo, and Chilo announces that he has become a Christian too. Tigellinus has guards apprehend Chilo who

torture him to retract what he said about Nero.

Chilo refuses, and Tigellinus has his tongue pulled out.

Tigellinus comes up with a new idea for a spectacle. He will have a Christian hang on a cross while devoured by a real life bear. The Roman audience has begun to believe the Christian divinity will conquer Rome. When it is time for the bear scene, to the audience’s surprise two guards drag out Chilo, naked and decrepit from his broken bones. He lay calm, awaiting his fate with peace. They nail him to a low cross so a bear can reach up to him. The bear is curious but does not attack Chilo, as if in pity for the man. As Chilo looks up, he smiles as if in a vision of wonder, and then dies. A voice from the top of the amphitheater yells out, “Peace to the martyrs,” silencing the audience.

After the burning of the Christians as torches in Nero’s garden, there are not many Christians left. The Roman population is convinced the Christian God will take revenge. The rumors that Nero and Tigellinus are the real culprits of the fire spread through the city. To calm the populace more free food is provided. Vinicius is reassured that when Lygia dies he will be given her remains. He too has become emaciated from his stress. The thought of reuniting with her in the afterlife consoles him. Ursus too is consoled in the thought of serving Lygia in the afterlife. The prison guards admire the mild good temper of the gentle giant.

###

My

Comment:

Good Lord, the degradation on the Christians sinks lower and lower. The crowd is bored with the slaughter, so the powers have to devise more disgusting spectacles to hold the audience's interest. The slaughter of the Christians is a holocaust, which reminded me of Nazi Germany. The book, however, was published in 1896, well before WWII.

Michelle’s

Reply:

This was so very hard to

read about! It's hard to fathom how people could watch the Christians

brutalized in the "games" and see them as entertainment. It's very

disturbing.

On a lighter note, the reconciliation between Chilo and Glaucus was unexpected but touching, wasn't it? I was really glad that it happened.

My

Reply to Michelle:

It was very hard to read

Michelle. The blackness of the Roman people’s hearts to watch and be

entertained by this is chilling. I don’t believe the author is exaggerating. I

do think the Roman people were numb to cruelty.

Chilo surprised me at every turn. I did not expect him to betray the Christians nor convert to Christianity nor stand up for Christianity and accept martyrdom. He was a weak man who was strengthened by the grace of God and did the right thing in the end

Frances’s

Comment:

Over the weekend my

husband and I watched the movie “Gladiator,” which as many of you who saw it

when it first came out about 20 years may remember well. It takes place during

the reign of the Emperor Commodus (177-192 A.D.), while the events in Quo Vadis

occurred during the reign of Nero, around 54-68 A.D. (Christians were

persecuted, tortured and martyred during the first through fourth centuries, as

you doubtless know.)

Two observations: 1).

After seeing the film, I looked up reviews of it.

I was not that surprised

to read in one review that all mention of Jesus and Christianity were

deliberately left out. The hero, played by the actor Russell Crowe, dies a

martyr’s death; the afterlife he goes to resembles the Elysian Fields of

ancient mythology. Above, Manny referred to the blackness of the Roman people’s

hearts, to watch such cruelty as entertainment. This is not apparent in “Gladiator.”

Spectators are watching “the games.” We can deduce their attitudes, but they

aren’t highlighted by the filmmaker.

2) Now go to Tom Holland’s brilliant book, Dominion. In it Holland stresses he was surprised to learn what a savage and alien place the ancient world was. And he discovered there was a certain innocence about the citizens’ callousness: they lived with it, not aware of their attitudes toward savagery and slavery. Caring, sensitivity, respect for human rights: these were the gifts of Christianity. Our culture at large doesn’t recognize that the values of Western civilization trace their roots to early Christianity, but they do. I find it particularly sad that the makers of the movie “Gladiator” chose to ignore this. Quo Vadis did not.

My

Reply to Frances:

Oh I love the movie

Gladiator and caught a scene that same day you were watching Frances. My wife

was watching it. Unfortunately I had to go out.

I think the Roman people were probably mixed on the gladiatorial games. But the fact that they were a big source of entertainment suggests that most supported them. As with anything, repetition without challenge will normalize all sorts of hideous behavior. There are many things in society today that is accepted as normal that would have been disgraceful 100 years ago. You can probably make a list resulting from the sexual revolution.

Kerstin’s

Comment:

I found these scenes very

disturbing too. I actually skipped much of it, it was too much.

From the beginning Sienkiewicz has been very consistent in depicting the Romans as people without the gentling influences of Christianity. It exposes the inner tension that must exist in a person who will love those close to him and not care one whit about anyone else.

###

The

first excerpt I’ll post is from Chapter LXI; Nero, Tigillianus, and Chilo are

walking through Nero’s garden with the Christians hung on poles as human torches.

Darkness had not come

when the first waves of people began to flow into Cæsar's gardens. The crowds,

in holiday costume, crowned with flowers, joyous, singing, and some of them

drunk, were going to look at the new, magnificent spectacle. Shouts of

"Semaxii! Sarmentitii!" were heard on the Via Tecta, on the bridge of

Æmilius, and from the other side of the Tiber, on the Triumphal Way, around the

Circus of Nero, and off towards the Vatican Hill. In Rome people had been seen

burnt on pillars before, but never had any one seen such a number of victims.

Cæsar and Tigellinus,

wishing to finish at once with the Christians and also to avoid infection,

which from the prisons was spreading more and more through the city, had given

command to empty all dungeons, so that there remained in them barely a few tens

of people intended for the close of the spectacles. So, when the crowds had

passed the gates, they were dumb with amazement. All the main and side alleys,

which lay through dense groves and along lawns, thickets, ponds, fields, and

squares filled with flowers, were packed with pillars smeared with pitch, to

which Christians were fastened. In higher places, where the view was not

hindered by trees, one could see whole rows of pillars and bodies decked with

flowers, myrtle, and ivy, extending into the distance on high and low places,

so far that, though the nearest were like masts of ships, the farthest seemed

colored darts, or staffs thrust into the earth. The number of them surpassed

the expectation of the multitude. One might suppose that a whole nation had

been lashed to pillars for Rome's amusement and for Cæsar's. The throng of

spectators stopped before single masts when their curiosity was roused by the

form or the sex of the victim; they looked at the faces, the crowns, the

garlands of ivy; then they went farther and farther, asking themselves with

amazement, "Could there have been so many criminals, or how could children

barely able to walk have set fire to Rome?" and astonishment passed by

degrees into fear.

Meanwhile darkness came,

and the first stars twinkled in the sky. Near each condemned person a slave

took his place, torch in hand; when the sound of trumpets was heard in various

parts of the gardens, in sign that the spectacle was to begin, each slave put

his torch to the foot of a pillar. The straw, hidden under the flowers and

steeped in pitch, burned at once with a bright flame which, increasing every

instant, withered the ivy, and rising embraced the feet of the victims. The

people were silent; the gardens resounded with one immense groan and with cries

of pain. Some victims, however, raising their faces toward the starry sky,

began to sing, praising Christ. The people listened. But the hardest hearts

were filled with terror when, on smaller pillars, children cried with shrill

voices, "Mamma! Mamma!" A shiver ran through even spectators who were

drunk when they saw little heads and innocent faces distorted with pain, or

children fainting in the smoke which began to stifle them. But the flames rose,

and seized new crowns of roses and ivy every instant. The main and side alleys

were illuminated; the groups of trees, the lawns, and the flowery squares were

illuminated; the water in pools and ponds was gleaming, the trembling leaves on

the trees had grown rose-colored, and all was as visible as in daylight. When

the odor of burnt bodies filled the gardens, slaves sprinkled between the

pillars myrrh and aloes prepared purposely. In the crowds were heard here and

there shouts,—whether of sympathy or delight and joy, it was unknown; and they

increased every moment with the fire, which embraced the pillars, climbed to

the breasts of the victims, shrivelled with burning breath the hair on their

heads, threw veils over their blackened faces, and then shot up higher, as if

showing the victory and triumph of that power which had given command to rouse

it.

At the very beginning of

the spectacle Cæsar had appeared among the people in a magnificent quadriga of

the Circus, drawn by four white steeds. He was dressed as a charioteer in the

color of the Greens,—the court party and his. After him followed other chariots

filled with courtiers in brilliant array, senators, priests, bacchantes, naked

and crowned, holding pitchers of wine, and partly drunk, uttering wild shouts.

At the side of these were musicians dressed as fauns and satyrs, who played on

citharas, formingas, flutes, and horns. In other chariots advanced matrons and

maidens of Rome, drunk also and half naked. Around the quadriga ran men who

shook thyrses ornamented with ribbons; others beat drums; others scattered

flowers.

All that brilliant throng

moved forward, shouting, "Evoe!" on the widest road of the garden,

amidst smoke and processions of people. Cæsar, keeping near him Tigellinus and

also Chilo, in whose terror he sought to find amusement, drove the steeds

himself, and, advancing at a walk, looked at the burning bodies, and heard the

shouts of the multitude. Standing on the lofty gilded chariot, surrounded by a

sea of people who bent to his feet, in the glitter of the fire, in the golden

crown of a circus-victor, he was a head above the courtiers and the crowd. He

seemed a giant. His immense arms, stretched forward to hold the reins, seemed

to bless the multitude. There was a smile on his face and in his blinking eyes;

he shone above the throng as a sun or a deity, terrible but commanding and mighty.

At times he stopped to

look with more care at some maiden whose bosom had begun to shrink in the

flames, or at the face of a child distorted by convulsions; and again he drove

on, leading behind him a wild, excited retinue. At times he bowed to the people,

then again he bent backward, drew in the golden reins, and spoke to Tigellinus.

At last, when he had reached the great fountain in the middle of two crossing

streets, he stepped from the quadriga, and, nodding to his attendants, mingled

with the throng.

He was greeted with

shouts and plaudits. The bacchantes, the nymphs, the senators and Augustians,

the priests, the fauns, satyrs, and soldiers surrounded him at once in an

excited circle; but he, with Tigellinus on one side and Chilo on the other,

walked around the fountain, about which were burning some tens of torches;

stopping before each one, he made remarks on the victims, or jeered at the old

Greek, on whose face boundless despair was depicted.

At last he stood before a lofty mast decked with myrtle and ivy. The red tongues of fire had risen only to the knees of the victim; but it was impossible to see his face, for the green burning twigs had covered it with smoke. After a while, however, the light breeze of night turned away the smoke and uncovered the head of a man with gray beard falling on his breast.

###

The

second excerpt is from Chilo’s crucifixion and death in Chapter LXII.

But others spoke of

Chilo.

"What has happened

to him?" asked Eprius Marcellus. "He delivered them himself into the

hands of Tigellinus; from a beggar he became rich; it was possible for him to

live out his days in peace, have a splendid funeral, and a tomb: but, no! All

at once he preferred to lose everything and destroy himself; he must, in truth,

be a maniac."

"Not a maniac, but

he has become a Christian," said Tigellinus.

"Impossible!"

said Vitelius.

"Have I not

said," put in Vestinius, "'Kill Christians if ye like; but believe me

ye cannot war with their divinity. With it there is no jesting'? See what is

taking place. I have not burned Rome; but if Cæsar permitted I would give a

hecatomb at once to their divinity. And all should do the same, for I repeat:

With it there is no jesting! Remember my words to you."

"And I said

something else," added Petronius. "Tigellinus laughed when I said

that they were arming, but I say more,—they are conquering."

"How is that? how is

that?" inquired a number of voices.

"By Pollux, they

are! For if such a man as Chilo could not resist them, who can? If ye think

that after every spectacle the Christians do not increase, become coppersmiths,

or go to shaving beards, for then ye will know better what people think, and

what is happening in the city."

"He speaks pure

truth, by the sacred peplus of Diana," cried Vestinius.

But Barcus turned to

Petronius.

"What is thy

conclusion?"

"I conclude where ye

began,—there has been enough of bloodshed."

Tigellinus looked at him

jeeringly,—"Ei!—a little more!"

"If thy head is not

sufficient, thou hast another on thy cane," said Petronius.

Further conversation was

interrupted by the coming of Cæsar, who occupied his place in company with

Pythagoras. Immediately after began the representation of "Aureolus,"

to which not much attention was paid, for the minds of the audience were fixed

on Chilo. The spectators, familiar with blood and torture, were bored; they

hissed, gave out shouts uncomplimentary to the court, and demanded the bear

scene, which for them was the only thing of interest. Had it not been for gifts

and the hope of seeing Chilo, the spectacle would not have held the audience.

At last the looked-for

moment came. Servants of the Circus brought in first a wooden cross, so low

that a bear standing on his hind feet might reach the martyr's breast; then two

men brought, or rather dragged in, Chilo, for as the bones in his legs were

broken, he was unable to walk alone. They laid him down and nailed him to the

wood so quickly that the curious Augustians had not even a good look at him,

and only after the cross had been fixed in the place prepared for it did all

eyes turn to the victim. But it was a rare person who could recognize in that

naked man the former Chilo. After the tortures which Tigellinus had commanded,

there was not one drop of blood in his face, and only on his white beard was

evident a red trace left by blood after they had torn his tongue out. Through

the transparent skin it was quite possible to see his bones. He seemed far

older also, almost decrepit. Formerly his eyes cast glances ever filled with

disquiet and ill-will, his watchful face reflected constant alarm and

uncertainty; now his face had an expression of pain, but it was as mild and

calm as faces of the sleeping or the dead. Perhaps remembrance of that thief on

the cross whom Christ had forgiven lent him confidence; perhaps, also, he said

in his soul to the merciful God,

"O Lord, I bit like

a venomous worm; but all my life I was unfortunate. I was famishing from

hunger, people trampled on me, beat me, jeered at me. I was poor and very

unhappy, and now they put me to torture and nail me to a cross; but Thou, O

Merciful, wilt not reject me in this hour!" Peace descended evidently into

his crushed heart. No one laughed, for there was in that crucified man

something so calm, he seemed so old, so defenceless, so weak, calling so much

for pity with his lowliness, that each one asked himself unconsciously how it

was possible to torture and nail to crosses men who would die soon in any case.

The crowd was silent. Among the Augustians Vestinius, bending to right and

left, whispered in a terrified voice, "See how they die!" Others were looking for the bear, wishing the

spectacle to end at the earliest.

The bear came into the

arena at last, and, swaying from side to side a head which hung low, he looked

around from beneath his forehead, as if thinking of something or seeking

something. At last he saw the cross and the naked body. He approached it, and

stood on his hind legs; but after a moment he dropped again on his fore-paws,

and sitting under the cross began to growl, as if in his heart of a beast pity

for that remnant of a man had made itself heard.

Cries were heard from

Circus slaves urging on the bear, but the people were silent.

Meanwhile Chilo raised

his head with slow motion, and for a time moved his eyes over the audience. At

last his glance rested somewhere on the highest rows of the amphitheatre; his

breast moved with more life, and something happened which caused wonder and

astonishment. That face became bright with a smile; a ray of light, as it were,

encircled that forehead; his eyes were uplifted before death, and after a while

two great tears which had risen between the lids flowed slowly down his face.

And he died.

At that same moment a

resonant manly voice high up under the velarium exclaimed,—

"Peace to the

martyrs!" Deep silence reigned in the amphitheatre.

This video clip is not from any of the movies but a historical retelling of the events.

As you can see, the novel follows the historical events very closely.

No comments:

Post a Comment