This is Post #2 of Henryk Sienkiewicz’s historical

novel, Quo Vadis.

You can find Post #1 here.

Chapters 7 thru 14

Summary

At the palace, Acte, Nero’s former mistress but now a palace attendant, was assigned to prepare Lygia for the feast. Lygia undesiring to attend fearfully let Acte dress her. A bond formed between the two of them. Acte, educated, had read the writings of Paul of Tarsus, and compassionately advised Lygia on how to act in Nero’s company. They discussed the mystery of why she had been brought to Nero’s palace. To Acte’s surprise, Lygia, though lovely before, had transformed into the most beautiful of young women.

They entered the feast and walked among eminent

noblemen and senators. Lygia was

frightened and wanted to escape. She saw

Vinicius come in with Petronius. Acte

took her to the dining area and there was Caesar himself. Vinicius approached her, and she found him

handsome. He pledged to her again. She asked him why she had been taken to

Caesar’s palace, and Vinicius calmed her by saying he would stay by her, and promised

to take her to his house. He sat by her

at table. At one point, drunk, he

grabbed her by the arm, but Acte interfered by calling attention to Nero. It was true.

Lygia had caught Nero’s eye, and Vinicius backed down.

Petronius and Nero have a conversation about

Vinicius’s attraction to Lygia. Other

noblemen join in the conversation, a sort of imperious male talk of life and

women. Finally Poppaea, Nero’s wife entered

and became the center of attention.

Lygia turned to Vinicius to ask if such a beautiful woman could be Poppaea,

who she had heard as a Christian was notoriously evil. But Vinicius, even more drunk, grabbed at her

again. Her once trust in Vinicius had

now turned dread. What stopped him were

the musicians that had come to perform.

Music, reciting of poetry, and dramatic dialogues became the center of

attention. Athletes then came,

wrestlers performing for entertainment.

Clowns and dancers followed. The

feast was turning into a bacchanal, and guests were undressing. Drunken guests were shouting and grabbing at

the dancers.

Finally Vinicius blurts out to Lygia that Nero had

taken her from Aulus for him, and that the next evening he will have her

brought to his home. Wildly drunk he

rose and put his arms around her neck and pressed his lips on hers. But Lygia’s giant guard, Ursus, pulled him

off her and tossed him aside. The giant

picked up his queen and took her back to her room. Vinicius called for her and then fell drunk

to the floor. Many of the guests were

also lying about drunk.

Ursus had taken Lygia to Acte’s apartments. Lygia and Ursus want to leave the palace

altogether and are ready to return to Aulus’s home, but Acte tells them that it

would be an insult to Caesar in which he would take his revenge on Aulus and

Pomponia, and Lygia would still be forced to go to Vinicius. Acte tries to convince Lygia to be resigned

to her fate given the power of all the men involved. Lygia will not accept it. She and Ursus drop to their knees and pray

which moves Acte. After prayer, Lygia

comes up with a new plan. When Vinicius’

slaves come to take her away, Ursus and scores of other Christians will

intercept the entourage and whisk Lygia away and make their way to the far

reaches of the empire.

Acte did not like the plan. She did not think it would work and could not understand why Lygia would refuse to be Vinicius’ concubine or perhaps possibly even wife. But she marvels at Lygia’s calm as they rest, Lygia falling asleep while Acte awake in dread. In the afternoon, while waiting for evening for Vinicius’ retinue to arrive and take her away, Lygia and Acte take a walk in the garden. Poppaea comes upon them and noticing Lygia’s beauty wonders if Nero intends to take her for a mistress. But Lygia explains that the plan was for Vinicius to taker her that evening and implores Poppaea to persuade Caesar to send her back to Aulus’s home. Relieved, Poppaea tells her that evening Lygia will be Vinicius’ whore and walks away. Evening comes and Vinicius’ retinue arrives, and Lygia hugs Acte goodbye.

Meanwhile Vinicius was waiting at his house with Petronius for Lygia to arrive, having prepared to start a feast when she got there. Petronius admonishes Vinicius about his behavior at Nero’s feast. It was no way to win over a lady. As the retinue travels toward Vinicius’s home, it is overwhelmed by Christians who free Lygia. Ursus kills a man who tried to whisk away Lygia, and Ursus and Lygia abscond into the dark streets of the city. The slaves who had ushered Lygia in the retinue break the news to Vicinius, and Vinicius in his anger kills an old slave who had taken care of him as a child.

After flogging the rest of the slaves, Vinicius in his anger cannot rest. He first contemplates a theory that Aulus and Pomponia had sent a party to attack the retinue. He vows revenge against them. Then he settles on a theory that Nero himself had attacked the retinue to take Lygia. Here too he vows revenge but then in the reasoning of Nero’s superior power he resigns to have lost her. He decides to go to Nero’s palace to discern if she is there.

At the palace Vinicius finds that Nero has been occupied with the illness of his newborn child Augusta, and could not have been the source of Lygia’s escape. Acte explains to him that the child was with Poppaea when they came across Lygia in the garden, and that now Poppaea suspects that Lygia has cast a spell on Augusta. If Augusta dies, both Nero and Poppaea will blame Lygia and she will be killed. She also tells him that Lygia had loved him until his brutish behavior at Nero’s feast. That she loved him cut to his heart, and he felt immense guilt.

Vinicius and Petronius make a plan to try to find her. They send slaves to watch the exits of the city. They send patrols out to find her and Ursus. They deduce that only their co-religionists would have gotten together and freed her. To relieve Vinicius of his stress, Petronius offers him his beautiful female slave, Eunice. Vicinius has no interest and Eunice resists. Petronius has Eunice flogged nonetheless for resisting, suspecting that she refused to leave his household because she’s in love with someone there.

The next morning, a man who Eunice knows and who Petronius suspects is the man Eunice loves, presents himself to Petronius and Vinicius. His name is Chilo Chilonides, a man of many talents and learning, and says he will find Lygia for them. They promise to reward him with a small fortune if he delivers her. His first order of business is to figure out what is her religion since only co-religionists would have taken such an initiative. When he learns that Lygia had drawn a fish symbol, he concludes that she might be a Christian. Petronius and Vinicius find it impossible to believe she is a Christian. They hold such prejudiced notions about Christians and their practices.

A few days later, Augusta dies, and Nero is in a rage. Petronius tried to console him. Chilo returns to confirm that the fish symbol stands for Jesus Christ, the god of the Christians. Chilo then reveals that he through his investigation has “become Christian” himself. He tells them the story of how he met with a freedman, Pansa, who is a Christian, and Pansa brought him to a house of prayer, and that by doing so he has infiltrated the Christians, becoming friends with an old man named Euricius. The Christians seem to trust him and has been led into their company. Through this he hopes to find Lygia. Vinicius provides him with the necessary money to maintain this cover.

###

Celia

Commented:

Manny, your summaries are like gold!! I have read through Chapter 7 so am not reading the summary yet. I AM loving the book and its message. Lygia reminds me of St Cecilia, my patron saint. She converted her pagan husband, as I think Lygia will do. I have seen at least three versions of this book. The one I started with was awful. I could not follow the story. I am now reading the Kindle Unlimited version which is easy to follow and well written. Yet a third version is the hardback that I borrowed to get page numbers. It too is good although I am not reading it.

Kerstin

Commented:

Sienkiewiecz does a great

job in describing the decadent, crude, and even brutish life of the Roman upper

class without himself using crude language. The contrast to the innocent Lygia

could not be greater.

I do see some types

emerging. We'll see if they hold up.

Petronius: He represents

all that is noble in the Pagan world of Rome. He is still a Pagan though, and

so does not have a full understanding of virtues, vices, and morals, which is

only possible in light of Christ.

Vinicius: He is the

passionate young buck who even from a Roman perspective needs gentling and

civilizing. He spent years fighting in the provinces, not exactly a place to

learn the ways of a gentleman. His attraction to Lygia is not just her outer

beauty, but the inner beauty formed by her Christian faith. He doesn't realize

it yet, but to win her he must undergo a profound change of heart. This will be

quite an uphill climb for him since he messed up so badly.

Lygia: She represents the emerging Christianity in all its splendor and beauty. It is her virtue that beguiles, her meekness and gentleness. At the same time she is a warrior in her own right, her weapons are prayer and full submission to God. She will not compromise her values. The newness of Christianity is also a stumbling block for the surrounding Pagan culture, as it has no reference whatsoever and rumors abound. Pomponia instructed Lygia how to navigate these obstacles. We will see how she will fare on her own. Up to now she had been so sheltered and innocent.

Bruce

Commented:

Regarding Nero, the early

Church historian Eusebius in his Ecclesiastical history recounts, “When Nero’s

power was firmly established, he gave himself up to unholy practices and took

up arms against the God of the universe.” “His perverse and extraordinary

madness led him to senselessly destroy innumerable lives. In his lust for

blood, he did not spare even his nearest and dearest, but in various ways did

away with mother, brothers, and wife alike, and countless other members of his

family,” as well as his former tutor and Stoic philosopher Seneca, “as if they

were personal and public enemies.”

The Roman historian

Tacitus, in his Annals, says this about Nero’s persecution of the Christians:

“But all human efforts, all the lavish gifts of the emperor, and all the

sacrificing to the gods, did not banish the sinister popular belief that the

fire was ordered by Nero. To destroy this rumor, Nero fastened the guilt and

inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations,

called Christians by the populace.”

Tacitus continues, “At first, those who confessed were arrested. Then, on their evidence, a huge multitude was convicted, not so much of the crime of fire than for hatred of mankind. These deaths were accompanied by derision: covered in animal skins they were to perish torn by dogs, or affixed to crosses to be burnt as torches when the sun set. Nero offered his gardens for the show and staged games in the Circus, mixing with the crowd in the garb of a driver riding a chariot,” which was behavior not befitting an emperor. “This roused pity. Although guilty and deserving of extreme measures, the Christians’ annihilation seemed to arise not from public utility but for one man’s brutality.”

My

Reply to Bruce:

Thank you Bruce. It seems the novel is following the history very closely.

###

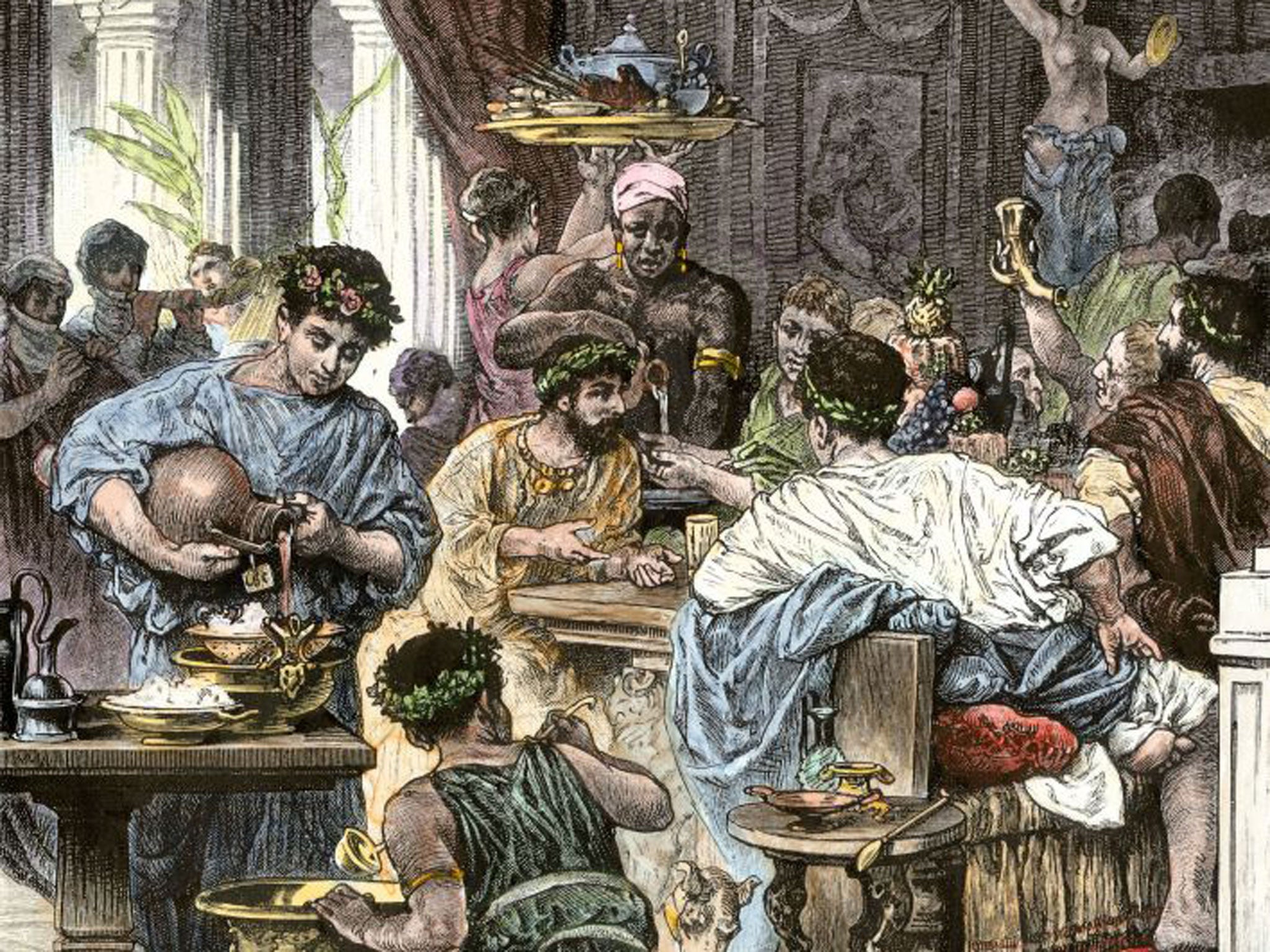

Excerpt

from Chapter VII, a scene from Nero’s wild and drunken feast where Lygia was

completely out of place.

The pulse beat oppressively in Lygia's hands and temples. A feeling seized her that she was flying into some abyss, and that Vinicius, who before had seemed so near and so trustworthy, instead of saving was drawing her toward it. And she felt sorry for him. She began again to dread the feast and him and herself. Some voice, like that of Pomponia, was calling yet in her soul, "O Lygia, save thyself!" But something told her also that it was too late; that the one whom such a flame had embraced as that which had embraced her, the one who had seen what was done at that feast and whose heart had beaten as hers had on hearing the words of Vinicius, the one through whom such a shiver had passed as had passed through her when he approached, was lost beyond recovery. She grew weak. It seemed at moments to her that she would faint, and then something terrible would happen. She knew that, under penalty of Cæsar's anger, it was not permitted any one to rise till Cæsar rose; but even were that not the case, she had not strength now to rise.

Meanwhile it was far to

the end of the feast yet. Slaves brought new courses, and filled the goblets

unceasingly with wine; before the table, on a platform open at one side,

appeared two athletes to give the guests a spectacle of wrestling.

They began the struggle

at once, and the powerful bodies, shining from olive oil, formed one mass;

bones cracked in their iron arms, and from their set jaws came an ominous

gritting of teeth. At moments was heard the quick, dull thump of their feet on

the platform strewn with saffron; again they were motionless, silent, and it

seemed to the spectators that they had before them a group chiselled out of

stone. Roman eyes followed with delight the movement of tremendously exerted

backs, thighs, and arms. But the struggle was not too prolonged; for Croton, a

master, and the founder of a school of gladiators, did not pass in vain for the

strongest man in the empire. His opponent began to breathe more and more

quickly: next a rattle was heard in his throat; then his face grew blue;

finally he threw blood from his mouth and fell.

A thunder of applause

greeted the end of the struggle, and Croton, resting his foot on the breast of

his opponent, crossed his gigantic arms on his breast, and cast the eyes of a

victor around the hall.

Next appeared men who

mimicked beasts and their voices, ball-players and buffoons. Only a few persons

looked at them, however, since wine had darkened the eyes of the audience. The

feast passed by degrees into a drunken revel and a dissolute orgy. The Syrian

damsels, who appeared at first in the bacchic dance, mingled now with the

guests. The music changed into a disordered and wild outburst of citharas,

lutes, Armenian cymbals, Egyptian sistra, trumpets, and horns. As some of the

guests wished to talk, they shouted at the musicians to disappear. The air,

filled with the odor of flowers and the perfume of oils with which beautiful

boys had sprinkled the feet of the guests during the feast, permeated with

saffron and the exhalations of people, became stifling; lamps burned with a dim

flame; the wreaths dropped sidewise on the heads of guests; faces grew pale and

were covered with sweat. Vitelius rolled under the table. Nigidia, stripping

herself to the waist, dropped her drunken childlike head on the breast of

Lucan, who, drunk in like degree, fell to blowing the golden powder from her

hair, and raising his eyes with immense delight. Vestinius, with the

stubbornness of intoxication, repeated for the tenth time the answer of Mopsus

to the sealed letter of the proconsul. Tullius, who reviled the gods, said,

with a drawling voice broken by hiccoughs,—"If the spheros of Xenophanes

is round, then consider, such a god might be pushed along before one with the

foot, like a barrel."

But Domitius Afer, a

hardened criminal and informer, was indignant at the discourse, and through

indignation spilled Falernian over his whole tunic. He had always believed in

the gods. People say that Rome will perish, and there are some even who contend

that it is perishing already. And surely! But if that should come, it is

because the youth are without faith, and without faith there can be no virtue.

People have abandoned also the strict habits of former days, and it never

occurs to them that Epicureans will not stand against barbarians. As for him,

he—As for him, he was sorry that he had lived to such times, and that he must

seek in pleasures a refuge against griefs which, if not met, would soon kill

him.

When he had said this, he

drew toward him a Syrian dancer, and kissed her neck and shoulders with his

toothless mouth. Seeing this, the consul Memmius Regulus laughed, and, raising

his bald head with wreath awry, exclaimed,—"Who says that Rome is

perishing? What folly! I, a consul, know better. Videant consules! Thirty

legions are guarding our pax romana!"

Here he put his fists to

his temples and shouted, in a voice heard throughout the

triclinium,—"Thirty legions! thirty legions! from Britain to the Parthian

boundaries!" But he stopped on a sudden, and, putting a finger to his

forehead, said,—"As I live, I think there are thirty-two." He rolled

under the table, and began soon to send forth flamingo tongues, roast and

chilled mushrooms, locusts in honey, fish, meat, and everything which he had

eaten or drunk.

But the number of the

legions guarding Roman peace did not pacify Domitius.

No, no! Rome must perish;

for faith in the gods was lost, and so were strict habits! Rome must perish;

and it was a pity, for still life was pleasant there. Cæsar was gracious, wine

was good! Oh, what a pity!

No comments:

Post a Comment