This is sixth post of Henryk Sienkiewicz’s historical

novel, Quo Vadis.

You can find Post #1 here.

Post #2, here:

And Post #3 here.

And Post #4 here.

And Post #5 here.

Chapters 35 thru 41

Summary

On returning home, Vinicius finds Petronius sleeping in the tent of Petronius’s entourage. Petronius tells him that Caesar and the aristocracy will be going to Antium in a couple of days. He tells him how Nero is composing poetry and music, and how bad it is. They go inside to have dinner and talk. Vinicius tells Petronius that he is engaged to Lygia. Petronius is astonished but wishes him happiness. He warns him about Poppaea’s crush on him that could turn vindictive. But Vinicius tells him the Apostle Peter has said not a hair on his head will be harmed. Petroinus asks him if he’s become a Christian, and Vinicius says not yet. He still has to undergo instruction from Paul of Tarsus. Tired, Petronius leaves and Vinicius writes a letter to Lygia that he will have to go to Antium.

Nero’s huge entourage travels up to Antium in luxury and glittering opulence, including wild animals. The locals look on in awe. In the crowd was the Apostle Peter, Lygia, and Ursus who wanted a gaze at the emperor. Nero drove up in a chariot and loved the adulation from the crowd. Some voices in the crowd ridiculed Nero. As Nero perused the crowd his eyes were locked with that of Peter. At the end of the long retinue was Vinicius who seeing Peter and Lygia sprang from his chariot to greet them. Vinicius invites them to his home and they walk through the opulence of the city. Peter offers a humble prayer. Lygia observing the sunset over the city, Lygia thought it seemed like the city was on fire. Peter said the wrath of God was upon it.

Sometime later, Vinicius writes a letter to Lygia. He tells her about Caesar and the goings on at Antium. He writes about their future and living away on a shore. He writes about an event on a boat where Poppaea flirted with him again but Petronius redirected the attention. He tells her that Paul is there to instruct him in the faith.

Later, Vinicius writes another letter to Lygia. He tells her about his lessons with Paul. He tells her of his talks with Nero, and how Nero speaks about the burning of Troy and how a spectacle the burning of Rome would be. He warns her to be on guard and to go stay at the house of Aulus.

With Caesar shutting himself up for days to compose songs, Vinicius makes his way down to Rome to spend time with Lygia. Being with her on a beautiful evening, Vinicius feels total happiness. She returns his love with complete joy. He tells her that Paul has not finished with the lessons, and so not baptized yet, but he looks forward to it. He reiterates the fundamental Christian teachings and finds it convicting. In Christ’s love their love flourishes. Vinicius relates an exchange between Paul and Petronius, both philosophers of their worldviews. Paul points out the deficiencies of Petronius’s Epicureanism, and Petronius points out the pleasures of moderate sensuality. Vinicius suggests once he and Lygia are married they move down to Sicily to get away from Rome’s politics. Lygia welcomes it. As they are about to depart, they hear a series of what appear to be thunder but then recognize it as the roar of lions who are held captive for the games.

Back in Antium, Petronius is gaining Nero’s trust more and more, especially over his aristocratic rival Tigellinus. Petronius has the right touch of wit to praise Nero’s poetry and song without appearing obsequious. From the flattery, Nero’s ego swells even larger than before. Nero’s poetry tries to describe the burning of Troy, but Nero feels it falls flat because he has never seen a city burning. Tigellinus offers to burn Antium, but Nero says Antium is too small a town to simulate a burning city. Later, Petronius talks to Vinicius about Nero’s poetry and his growing madness. He tells of how Paul’s philosophy would bore him. Vinicius responds that Petronius doesn’t understand the joy that Christianity brings.

After singing a

number of his compositions, Nero makes Petronius and Vinicius go for a walk

with him. Nero wants to talk about his

talents, and Petronius continues to respond in the vein of flattery and yet not

obsequious. Nero just loves this, pointing

out how different Petronius is from Tigellinus.

In trust of Petronius, Nero whispers the bizarre reason for having his

mother and first wife murdered.

Petronius, feeling that he is in Nero’s total trust, suggests that Nero

publically approve Vinicius’s marriage to Lygia. Nero agrees, and going inside in front of his

court with Poppaea present, asks for a valuable necklace. He gives it to Vinicius as a wedding gift and

tells him to go to Rome to Lygia. Directly

thwarted, Poppaea is angered. Just then

a servant comes in telling that Rome is ablaze in fire.

###

My

Comment:

I finally looked up

Nero's Wikipedia's entry. He only lived

to thirty years old. So he's thirty when

the events of the novel occur and he has been emperor for 14 years. So he was very young when first made

emperor. There were some accomplishments

during his reign but he was not regarded as a stable man. His mother, the wife of the Emperor Claudius

was suspected of killing Claudius so that her son could become emperor, and given

his youth she expected to be the real power ruling the empire. It did work out for a time until Nero had her

killed to be in complete control. He

also had his stepbrother killed and then had his first wife killed to marry

Poppaea. The Wikipedia entry summarizes

what his contemporary historians thought of him:

Most Roman sources offer

overwhelmingly negative assessments of his personality and reign. Most

contemporary sources describe him as tyrannical, self-indulgent, and debauched.

The historian Tacitus claims the Roman people thought him compulsive and

corrupt. Suetonius tells that many Romans believed the Great Fire of Rome was

instigated by Nero to clear land for his planned "Golden House".

Tacitus claims Nero seized Christians as scapegoats for the fire and had them

burned alive, seemingly motivated not by public justice, but personal cruelty.

Some modern historians question the reliability of ancient sources on Nero's

tyrannical acts, considering his popularity among the Roman commoners. In the eastern

provinces of the Empire, a popular legend arose that Nero had not died and

would return. After his death, at least three leaders of short-lived, failed

rebellions presented themselves as "Nero reborn" to gain popular

support.

The most shocking thing I read in his bio was that he was born on December 15th! That's my birthday...lol. We share a birthday. What is shocking is that no one famous is born on that day. I have no one to look to for a bond of a birthdate. There isn't even a saint's feast day for me to identify with for December 15th. There are some obscure historical people born on that day and there are some obscure saints who are given that day as a feast day, but really no one of any note. Except now Nero!

Kerstin’s

Comment:

What is also made clear now is that Petronius enjoys the daily thrills in staying on Nero's good side when he knows full well that one faux pas can mean his death. Being at this high level and in the near constant presence of the Caesar Petronius has no life of his own left. So he tries to be the best of Nero's advisers and at the same time gets his kicks for besting him on a regular basis. Converting to the Christian faith is really no option for him, for the personal demands of the faith would not allow him to operate successfully at the place where he is at. It would mean certain death. Staying a Pagan means he has a fighting chance.

My

Reply:

Yes, one stumble will mean Petronius's death.

###

Some

of Sienkiewicz’s best writing is of the Roman pageantry. Here is a description of Nero’s entourage

traveling up to Antium. Excerpt from

Chapter 36.

Early on the morning of

that day herdsmen from the Campania, with sunburnt faces, wearing goat-skins on

their legs, drove forth five hundred she-asses through the gates, so that

Poppæa on the morrow of her arrival at Antium might have her bath in their

milk. The rabble gazed with delight and ridicule at the long ears swaying amid

clouds of dust, and listened with pleasure to the whistling of whips and the

wild shouts of the herdsmen. After the asses had gone by, crowds of youth

rushed forth, swept the road carefully, and covered it with flowers and needles

from pine-trees. In the crowds people whispered to each other, with a certain

feeling of pride, that the whole road to Antium would be strewn in that way

with flowers taken from private gardens round about, or bought at high prices

from dealers at the Porta Mugionis. As the morning hours passed, the throng

increased every moment. Some had brought their whole families, and, lest the

time might seem tedious, they spread provisions on stones intended for the new

temple of Ceres, and ate their prandium beneath the open sky. Here and there

were groups, in which the lead was taken by persons who had travelled; they

talked of Cæsar's present trip, of his future journeys, and journeys in

general. Sailors and old soldiers narrated wonders which during distant

campaigns they had heard about countries which a Roman foot had never touched.

Home-stayers, who had never gone beyond the Appian Way, listened with amazement

to marvellous tales of India, of Arabia, of archipelagos surrounding Britain in

which, on a small island inhabited by spirits, Briareus had imprisoned the

sleeping Saturn. They heard of hyperborean regions of stiffened seas, of the

hisses and roars which the ocean gives forth when the sun plunges into his

bath. Stories of this kind found ready credence among the rabble, stories

believed by such men even as Tacitus and Pliny. They spoke also of that ship

which Cæsar was to look at,—a ship which had brought wheat to last for two

years, without reckoning four hundred passengers, an equal number of soldiers,

and a multitude of wild beasts to be used during the summer games. This

produced general good feeling toward Cæsar, who not only nourished the populace,

but amused it. Hence a greeting full of enthusiasm was waiting for him.

Meanwhile came a

detachment of Numidian horse, who belonged to the pretorian guard. They wore

yellow uniforms, red girdles, and great earrings, which cast a golden gleam on

their black faces. The points of their bamboo spears glittered like flames, in

the sun. After they had passed, a procession-like movement began. The throng

crowded forward to look at it more nearly; but divisions of pretorian foot were

there, and, forming in line on both sides of the gate, prevented approach to

the road. In advance moved wagons carrying tents, purple, red, and violet, and

tents of byssus woven from threads as white as snow; and oriental carpets, and

tables of citrus, and pieces of mosaic, and kitchen utensils, and cages with

birds from the East, North, and West, birds whose tongues or brains were to go

to Cæsar's table, and vessels with wine and baskets with fruit. But objects not

to be exposed to bruising or breaking in vehicles were borne by slaves. Hence

hundreds of people were seen on foot, carrying vessels, and statues of

Corinthian bronze. There were companies appointed specially to Etruscan vases;

others to Grecian; others to golden or silver vessels, or vessels of

Alexandrian glass. These were guarded by small detachments of pretorian

infantry and cavalry; over each division of slaves were taskmasters, holding

whips armed at the end with lumps of lead or iron, instead of snappers. The

procession, formed of men bearing with importance and attention various

objects, seemed like some solemn religious procession; and the resemblance grew

still more striking when the musical instruments of Cæsar and the court were

borne past. There were seen harps, Grecian lutes, lutes of the Hebrews and

Egyptians, lyres, formingas, citharas, flutes, long, winding buffalo horns and

cymbals. While looking at that sea of instruments, gleaming beneath the sun in

gold, bronze, precious stones, and pearls, it might be imagined that Apollo and

Bacchus had set out on a journey through the world. After the instruments came

rich chariots filled with acrobats, dancers male and female, grouped

artistically, with wands in their hands. After them followed slaves intended,

not for service, but excess; so there were boys and little girls, selected from

all Greece and Asia Minor, with long hair, or with winding curls arranged in

golden nets, children resembling Cupids, with wonderful faces, but faces

covered completely with a thick coating of cosmetics, lest the wind of the

Campania might tan their delicate complexions.

And again appeared a

pretorian cohort of gigantic Sicambrians, blue-eyed, bearded, blond and red

haired. In front of them Roman eagles were carried by banner-bearers called

"imaginarii," tablets with inscriptions, statues of German and Roman

gods, and finally statues and busts of Cæsar. From under the skins and armor of

the soldier appeared limbs sunburnt and mighty, looking like military engines

capable of wielding the heavy weapons with which guards of that kind were furnished.

The earth seemed to bend beneath their measured and weighty tread. As if

conscious of strength which they could use against Cæsar himself, they looked

with contempt on the rabble of the street, forgetting, it was evident, that

many of themselves had come to that city in manacles. But they were

insignificant in numbers, for the pretorian force had remained in camp

specially to guard the city and hold it within bounds. When they had marched

past, Nero's chained lions and tigers were led by, so that, should the wish

come to him of imitating Dionysus, he would have them to attach to his

chariots. They were led in chains of steel by Arabs and Hindoos, but the chains

were so entwined with garlands that the beasts seemed led with flowers. The

lions and tigers, tamed by skilled trainers, looked at the crowds with green

and seemingly sleepy eyes; but at moments they raised their giant heads, and

breathed through wheezing nostrils the exhalations of the multitude, licking

their jaws the while with spiny tongues.

Now came Cæsar's vehicles and litters, great and small, gold or purple, inlaid with ivory or pearls, or glittering with diamonds; after them came another small cohort of pretorians in Roman armor, pretorians composed of Italian volunteers only; then crowds of select slave servants, and boys; and at last came Cæsar himself, whose approach was heralded from afar by the shouts of thousands. In the crowd was the Apostle Peter, who wished to see Cæsar once in life. He was accompanied by Lygia, whose face was hidden by a thick veil, and Ursus, whose strength formed the surest defence of the young girl in the wild and boisterous crowd. The Lygian seized a stone to be used in building the temple, and brought it to the Apostle, so that by standing on it he might see better than others.

###

In

almost in complete contrast to that raucous spectacle of the Romans on the trek

to Antium, we have in Chapter 39 a serene moment between Vinicuis and Lygia,

where they profess their love and Vinicuis expresses his desire to be a Christian.

The charm of the quiet

evening mastered them completely.

"How calm it is

here, and how beautiful the world is," said Vinicius, in a lowered voice.

"The night is wonderfully still. I feel happier than ever in life before.

Tell me, Lygia, what is this? Never have I thought that there could be such

love. I thought that love was merely fire in the blood and desire; but now for

the first time I see that it is possible to love with every drop of one's blood

and every breath, and feel therewith such sweet and immeasurable calm as if

Sleep and Death had put the soul to rest. For me this is something new. I look

on this calmness of the trees, and it seems to be within me. Now I understand

for the first time that there may be happiness of which people have not known

thus far. Now I begin to understand why thou and Pomponia Græcina have such

peace. Yes! Christ gives it."

At that moment Lygia

placed her beautiful face on his shoulder and said,—"My dear Marcus—"

But she was unable to continue. Joy, gratitude, and the feeling that at last

she was free to love deprived her of voice, and her eyes were filled with tears

of emotion.

Vinicius, embracing her

slender form with his arm, drew her toward him and said,—"Lygia! May the

moment be blessed in which I heard His name for the first time." "I

love thee, Marcus," said she then in a low voice.

Both were silent again,

unable to bring words from their overcharged breasts. The last lily reflections

had died on the cypresses, and the garden began to be silver-like from the

crescent of the moon. After a while Vinicius said,

"I know. Barely had

I entered here, barely had I kissed thy dear hands, when I read in thy eyes the

question whether I had received the divine doctrine to which thou art attached,

and whether I was baptized. No, I am not baptized yet; but knowest thou, my

flower, why? Paul said to me: 'I have convinced thee that God came into the

world and gave Himself to be crucified for its salvation; but let Peter wash

thee in the fountain of grace, he who first stretched his hands over thee and

blessed thee.' And I, my dearest, wish thee to witness my baptism, and I wish

Pomponia to be my godmother. This is why I am not baptized yet, though I

believe in the Saviour and in his teaching. Paul has convinced me, has

converted me; and could it be otherwise? How was I not to believe that Christ

came into the world, since he, who was His disciple, says so, and Paul, to whom

He appeared? How was I not to believe that He was God, since He rose from the

dead? Others saw Him in the city and on the lake and on the mountain; people

saw Him whose lips have not known a lie. I began to believe this the first time

I heard Peter in Ostrianum, for I said to myself even then: In the whole world

any other man might lie rather than this one who says, 'I saw.' But I feared

thy religion. It seemed to me that thy religion would take thee from me. I

thought that there was neither wisdom nor beauty nor happiness in it. But

to-day, when I know it, what kind of man should I be were I not to wish truth

to rule the world instead of falsehood, love instead of hatred, virtue instead

of crime, faithfulness instead of unfaithfulness, mercy instead of vengeance?

What sort of man would he be who would not choose and wish the same? But your religion

teaches this. Others desire justice also; but thy religion is the only one

which makes man's heart just, and besides makes it pure, like thine and

Pomponia's, makes it faithful, like thine and Pomponia's. I should be blind

were I not to see this. But if in addition Christ God has promised eternal

life, and has promised happiness as immeasurable as the all-might of God can

give, what more can one wish? Were I to ask Seneca why he enjoins virtue, if

wickedness brings more happiness, he would not be able to say anything

sensible. But I know now that I ought to be virtuous, because virtue and love

flow from Christ, and because, when death closes my eyes, I shall find life and

happiness, I shall find myself and thee. Why not love and accept a religion which

both speaks the truth and destroys death? Who would not prefer good to evil? I

thought thy religion opposed to happiness; meanwhile Paul has convinced me that

not only does it not take away, but that it gives. All this hardly finds a

place in my head; but I feel that it is true, for I have never been so happy,

neither could I be, had I taken thee by force and possessed thee in my house.

Just see, thou hast said a moment since, 'I love thee,' and I could not have

won these words from thy lips with all the might of Rome. O Lygia! Reason

declares this religion divine, and the best; the heart feels it, and who can

resist two such forces?"

Lygia listened, fixing on

him her blue eyes, which in the light of the moon were like mystic flowers, and

bedewed like flowers.

"Yes, Marcus, that is true!" said she, nestling her head more closely to his shoulder.

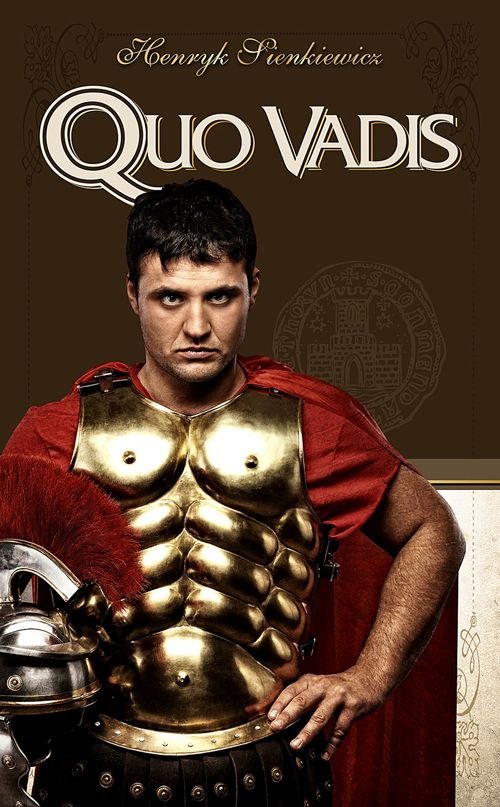

That is from the 2001 film version, I believe filmed in Polish.

No comments:

Post a Comment