The

first short story I read this year, the latest in the year I think I’ve ever

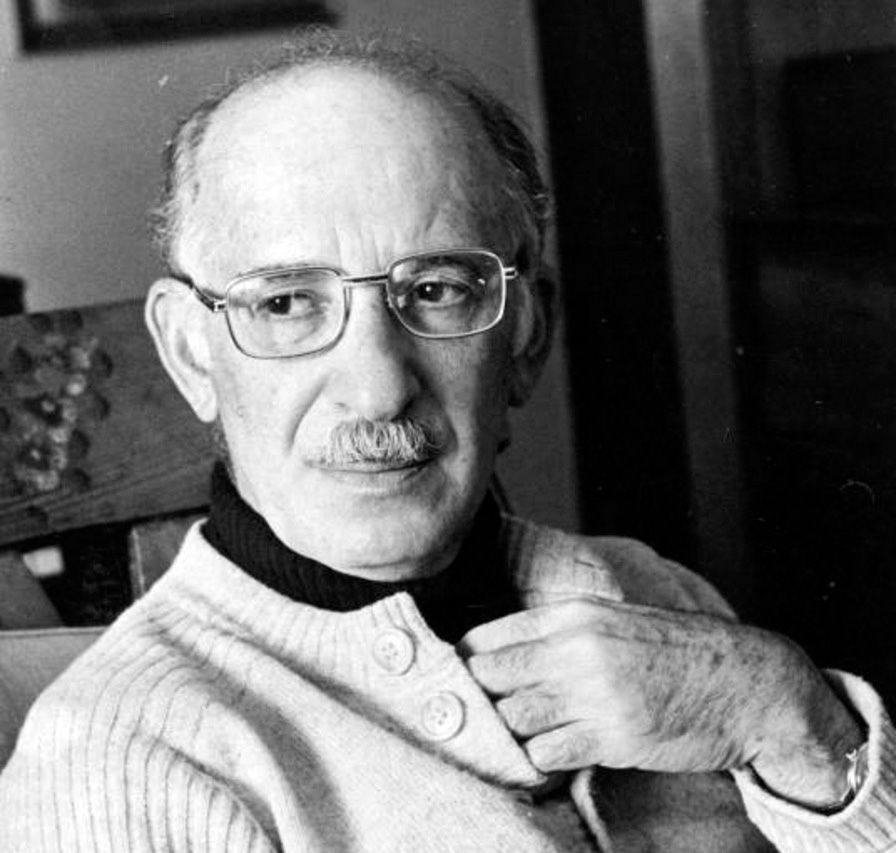

done so, way past mid-May, was a good one, “The Magic Barrel” by Bernard Malamud, and I’ve been giving it thought ever since. Born in New York City or more precisely the

borough of Brooklyn, and the son of Jewish immigrants, Malamud is known for his

well-crafted short stories about Jewish-American life, but also for several

novels, including The Natural. I have not read any of his novels, but I have

been impressed with his short stories.

In fact, one of the most prestigious awards for an American short story,

the PEN/Malamud Award for “excellence in the art of the short story", is

named in his honor.

“The

Magic Barrel” may be one of his best known, and a really fun read. You can find it online, here, in PDF if you

wish to read it ahead of my post.

The

story begins in New York City with an almost “Once upon a time” opening.

Not long ago there lived

in uptown New York, in a sma ll, almost meager room, though crowded with books,

Leo Finkle, a rabbinical student in the Yeshivah University. Finkle, after six

years of study, was to be ordained in June and had been advised by an

acquaintance that he might find it easier to win himself a congregation if he

were married. Since he had no present prospects of marriage, after two

tormented days of turning it over in his mind, he called in Pinye Salzman, a

marriage broker whose two-line advertisement he had read in the Forward.

The matchmaker appeared

one night out of the dark fourth-floor hallway of the graystone rooming house

where Finkle lived, grasping a black, strapped portfolio that had been worn

thin with use. Salzman, who had been long in the business, was of slight but

dignified build, wearing an old hat, and an overcoat too short and tight for

him. He smelled frankly of fish, which he loved to eat, and although he was

missing a few teeth, his presence was not displeasing, because of an amiable

manner curiously contrasted with mournful eyes. His voice, his lips, his wisp of

beard, his bony fingers were animated, but give him a moment of repose and his

mild blue eyes revealed a depth of sadness, a characteristic that put Leo a

little at ease although the situation, for him, was inherently tense.

As

a New Yorker, I know these characters, know them in the sense that similar

people walk in the neighborhoods I grew

up. The story was written in the 1950’s,

in what is sometimes considered the golden era of New York City. I’m not that old, but similar people were

around when I was growing up a couple of decades later. So we have the rabbinical student and a sort

of old world peddler who in this case hawks brides. It’s is interesting that Salzman smells of

fish, and fish is a motif that goes with the matchmaker throughout the story. But the sadness in his eyes is an interesting

detail that contrasts with Finkle’s youthfulness and inexperience.

Next

we get some critical information about Finkle.

He at once informed

Salzman why he had asked him to come, explaining that his home was in

Cleveland, and that but for his parents, who had married comparatively late in

life, he was alone in the world. He had for six years devoted himself almost

entirely to his studies, as a result of which, understandably, he had found

himself without time for a social life and the company of young women.

Therefore he thought it the better part of trial and error--of embarrassing

fumbling--to call in an experienced person to advise him on these matters. He

remarked in passing that the function of the marriage broker was ancient and

honorable, highly approved in the Jewish community, because it made practical

the necessary without hindering joy. Moreover, his own parents had been brought

together by a matchmaker. They had made, if not a financially profitable

marriage--since neither had possessed any worldly goods to speak of--at least a

successful one in the sense of their everlasting devotion to each other.

Salzman listened in embarrassed surprise, sensing a sort of apology. Later,

however, he experienced a glow of pride in his work, an emotion that had left

him years ago, and he heartily approved of Finkle.

Here

we learn of the parallel situation with Finkle’s parents in that they too have

met through a marriage broker, and their marriage was a happy one. But that was an old world relationship and

they lived in Cleveland. Finkle is now

in the modern world and lives in the big metropolis.

Next

Salzman takes out a half dozen cards with woman’s information on it. As Salzman tries to sell Finkle on the women

on the cards, what follows is some of the most entertaining dialogue I can

remember. I can’t quote all of it, but

here is a sample.

When Leo's eyes fell upon

the cards, he counted six spread out in Salzman's hand.

"So few?" he

asked in disappointment.

"You wouldn't

believe me how much cards I got in my office," Salzman replied. "The

drawers are already filled to the top, so I keep them now in a barrel, but is

every girl good for a new rabbi?"

Leo blushed at this,

regretting all he had revealed of himself in a curriculum vitae he had sent to

Salzman. He had thought it best to acquaint him with his strict standards and

specifications, but in having done so, felt he had told the marriage broker

more than was absolutely necessary.

He hesitantly inquired,

"Do you keep photographs of your clients on file?"

"First comes family,

amount of dowry, also what kind of promises," Salzman replied, unbuttoning

his tight coat and settling himself in the chair. "After comes pictures,

rabbi."

"Call me Mr. Finkle.

I'm not yet a rabbi."

Salzman said he would,

but instead called him doctor, which he changed to rabbi when Leo was not

listening too attentively.

Salzman adjusted his

horn-rimmed spectacles, gently cleared his throat and read in an eager voice

the contents of the top card:

"Sophie P.

Twenty-four years. Widow one year. No children. Educated high school and two

years college. Father promises eight thousand dollars. Has wonderful wholesale

business. Also real estate. On the mother's side comes teachers, also one

actor. Well known on Second Avenue."

Leo gazed up in surprise.

"Did you say a widow?"

"A widow don't mean

spoiled, rabbi. She lived with her husband maybe four months. He was a sick boy

she made a mistake to marry him."

"Marrying a widow

has never entered my mind."

"This is because you

have no experience. A widow, especially if she is young and healthy like this

girl, is a wonderful person to marry. She will be thankful to you the rest of

her life. Believe me, if I was looking now for a bride, I would marry a

widow."

Leo reflected, then shook

his head.

Salzman hunched his

shoulders in an almost imperceptible gesture of disappointment. He placed the

card down on the wooden table and began to read another:

"Lily H. High school

teacher. Regular. Not a substitute. Has savings and new Dodge car. Lived in

Paris one year. Father is successful dentist thirty-five years. Interested in

professional man. Well Americanized family. Wonderful opportunity."

"I know her

personally," said Salzman. "I wish you could see this girl. She is a

doll. Also very intelligent. All day you could talk to her about books and

theyater and whatnot. She also knows current events."

"I don't believe you

mentioned her age?"

"Her age?"

Salzman said, raising his brows. "Her age is thirty-two years."

"Leo said after a

while, "I'm afraid that seems a little too old.

Salzman let out a laugh.

"So how old are you, rabbi?"

"Twentyseven."

"So what is the

difference, tell me, between twenty-seven and thirty-two? My own wife is seven

years older than me. So what did I suffer?--Nothing. If Rothschild's daughter

wants to marry you, would you say on account her age, no?"

"Yes," Leo said

dryly.

Salzman shook off the no

in the eyes. "Five years don't mean a thing. I give you my word that when

you will live with her for one week you will forget her age. What does it mean

five years--that she lived more and knows more than somebody who is younger? On

this girl, God bless her, years are not wasted. Each one that it comes makes

better the bargain."

"What subject does

she teach in high school?"

"Languages. If you

heard the way she speaks French, you will think it is music. I am in the

business twenty-five years, and I recommend her with my whole heart. Believe

me, I know what I'm talking, rabbi."

"What's on the next

card?" Leo said abruptly.

There

is a folktale feel to this story, as the rabbi goes through female candidate

after female candidate. Leo, as he goes

through the list, can’t be satisfied with any of the women. But there are some questions that are brought

here that drive the story forward. What

is a right fit for a rabbi’s bride and how does Leo’s lack of experience with

the opposite sex cause him select or reject potential brides? The bulk of the story presents the drama

inherent in these abstract questions, and it’s quite entertaining. But I want

to move toward Leo’s central crises and then finally toward the climax. He finally accepts going out on a date with

the older woman, the one he rejected because of her age, Lily. And her probing questions, questions natural

of people trying to learn of each other, leads him to respond as to why he

chose to be a rabbi: "I was always interested in the Law."

"You saw revealed in

it the presence of the Highest?" He nodded and changed the subject.

"I understand that you spent a little time in Paris, Miss Hirschorn?"

"Oh, did Mr. Salzman tell you, Rabbi Finkle?" Leo winced but she went

on, "It was ages ago and almost forgotten. I remember I had to return for

my sister's wedding." And Lily would not be put off. "When," she

asked in a trembly voice, "did you become enamored of God?" 7 He

stared at her. Then it came to him that she was talking not about Leo Finkle,

but of a total stranger, some mystical figure, perhaps even passionate prophet

that Salzman had dreamed up for her--no relation to the living or dead. Leo

trembled with rage and weakness. The trickster had obviously sold her a bill of

goods, just as he had him, who'd expected to become acquainted with a young

lady of twenty-nine, only to behold, the moment he laid eyes upon her strained

and anxious face, a woman past thirty-five and aging rapidly. Only his self

control had kept him this long in her presence.

Lily

probed too deep. She hit a nerve, and

just like she had misrepresented her age, it became apparent that Leo had

misrepresented his faith, only not just to her, but to himself. Salzman had played up his devoutness, which

ultimately, days after the date came back to sting Leo into a self-realization.

He was infuriated with

the marriage broker and swore he would throw him out of the room the minute he

reappeared. But Salzman did not come that night, and when Leo's anger had

subsided, an unaccountable despair grew in its place. At first he thought this

was caused by his disappointment in Lily, but before long it became evident

that he had involved himself with Salzman without a true knowledge of his own

intent. He gradually realized--with an emptiness that seized him with six

hands--that he had called in the broker to find him a bride because he was

incapable of doing it himself. This terrifying insight he had derived as a

result of his meeting and conversation with Lily Hirschorn. Her probing

questions had somehow irritated him into revealing --to himself more than

her--the true nature of his relationship to God, and from that it had come upon

him, with shocking force, that apart from his parents, he had never loved

anyone. Or perhaps it went the other way, that he did not love God so well as

he might, because he had not loved man. It seemed to Leo that his whole life

stood starkly revealed and he saw himself for the first time as he truly

was--unloved and loveless. This bitter but somehow not fully unexpected

revelation brought him to a point to panic, controlled only by extraordinary

effort. He covered his face with his hands and cried.

The

experience of finding a wife has made him realize his “relationship to

God.” If he didn’t love anyone, he

didn’t love God, and of course this brings him to a spiritual crises,

questioning his faith and his vocation.

And finally we get to the climax. Leo falls in love with a girl of a picture

Salzman accidently left behind. He tries

to get Salzman to arrange a meeting.

Salzman refuses. This girl would

not be suitable for him. As it turns out

the girl is Salzman’s daughter who he has banish from his house because she is

“wild.” But Leo cannot let go.

Although he soon fell

asleep he could not sleep her out of his mind. He woke, beating his breast.

Though he prayed to be rid of her, his prayers went unanswered. Through days of

torment he endlessly struggled not to love her; fearing success, he escaped it.

He then concluded to convert her to goodness, himself to God. The idea

alternately nauseated and exalted him.

So he convinces himself he can convert her to

goodness. And so there is an

arrangement.

Leo was informed by

better that she would meet him on a certain corner, and she was there one

spring night, waiting under a street lamp. He appeared carrying a small bouquet

of violets and rosebuds. Stella stood by the lamp post, smoking. She wore white

with red shoes, which fitted his expectations, although in a troubled moment he

had imagined the dress red, and only the shoes white. She waited uneasily and

shyly. From afar he saw that her eyes--clearly her father's--were filled with

desperate innocence. He pictured, in her, his own redemption. Violins and lit

candles revolved in the sky. Leo ran forward with flowers out-thrust.

Around the corner,

Salzman, leaning against a wall, chanted prayers for the dead.

As ever, a wonderful review of a book you've read. Thanx Manny.

ReplyDeleteGod bless.

Excellent.

ReplyDeleteJan, you were able to comment! What did you do different?

DeleteThank you both. My analysis of short stories seem to be my most frequented posts. I should do more of them.

ReplyDelete