The occasion of thinking on this poem has to do with a recent event in our household that has, as it turns out, some correspondence to the event that inspired the poem. In the wee hours of Monday morning (overnight Sunday into Monday) I heard a big crash and ruckus in the hallway outside my bedroom. I initially thought that Matthew had gotten up in the middle of the night to go to the bathroom and stumbled into something. Then I heard another crash and ruckus. I got out of bed to investigate. Tiger, our cat, was chasing a mouse that had gotten inside the house. He was swiping and lunging at him with incredible violence, and at one point got him under his paw. The mouse played dead—he was motionless and I thought he was killed—but when Tiger lifted up his paw the mouse scooted away. This was all on the upstairs bedroom floor.

For

the next day and a half Tiger was on the hunt trying to sniff him out and wait

for him to come out. When my wife got home

Wednesday afternoon at about one o’clock she found him just inside the

vestibule on the main floor, downstairs from the bedrooms, lying dead. There must have been a battle. I guess he ran to try to get out but Tiger

caught him. Here’s a picture.

Poor little mouse. I thought him cute. I put the body across the street at an unkempt yard where feral cats live. Tiger as a kitten came from there, nine and a half years ago.

This

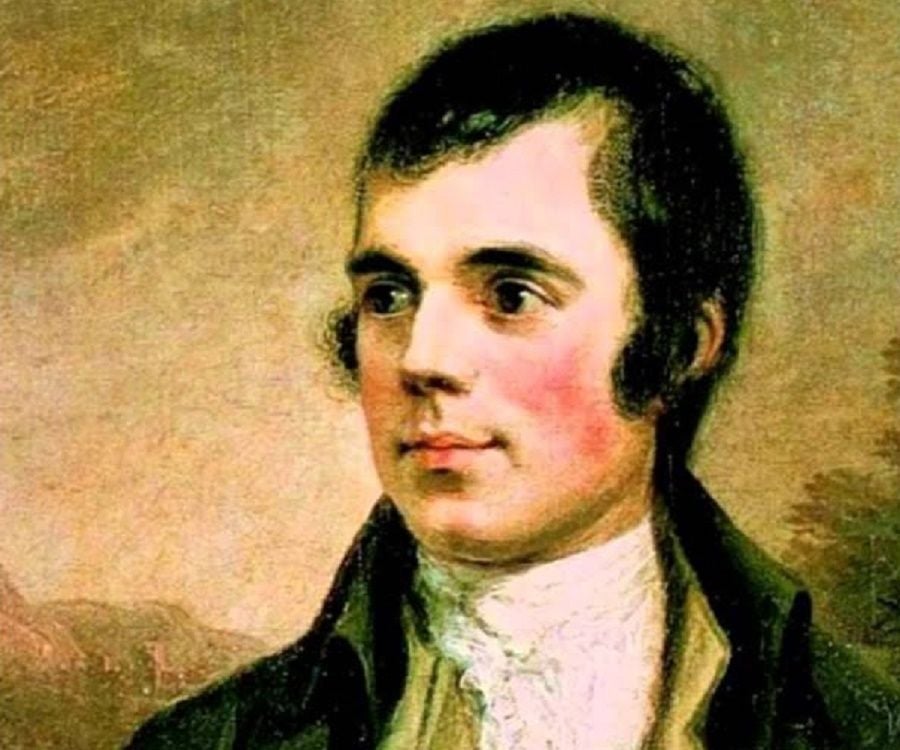

made me recall the Robert Burns’ poem, “To a Mouse,” where the poet felt a

compassion for a field mouse he had disturbed.

To a Mouse

By Robert Burns

On Turning her up in her

Nest, with the Plough, November 1785.

Wee, sleeket, cowran,

tim’rous beastie,

O, what a panic’s in thy

breastie!

Thou need na start awa

sae hasty,

Wi’ bickerin brattle!

I wad be laith to rin an’

chase thee

Wi’ murd’ring pattle!

I’m truly sorry Man’s

dominion

Has broken Nature’s

social union,

An’ justifies that ill

opinion,

Which makes thee startle,

At me, thy poor,

earth-born companion,

An’ fellow-mortal!

I doubt na, whyles, but

thou may thieve;

What then? poor beastie,

thou maun live!

A daimen-icker in a

thrave

’S a sma’ request:

I’ll get a blessin wi’

the lave,

An’ never miss ’t!

Thy wee-bit housie, too,

in ruin!

It’s silly wa’s the win’s

are strewin!

An’ naething, now, to big

a new ane,

O’ foggage green!

An’ bleak December’s

winds ensuin,

Baith snell an’ keen!

Thou saw the fields laid

bare an’ waste,

An’ weary Winter comin

fast,

An’ cozie here, beneath

the blast,

Thou thought to dwell,

Till crash! the cruel

coulter past

Out thro’ thy cell.

That wee-bit heap o’

leaves an’ stibble

Has cost thee monie a

weary nibble!

Now thou’s turn’d out,

for a’ thy trouble,

But house or hald,

To thole the Winter’s

sleety dribble,

An’ cranreuch cauld!

But Mousie, thou art no

thy-lane,

In proving foresight may

be vain:

The

best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men

Gang aft agley,

An’ lea’e us nought but

grief an’ pain,

For promis’d joy!

Still, thou art blest,

compar’d wi’ me!

The present only toucheth

thee:

But Och! I backward cast

my e’e,

On prospects drear!

An’ forward tho’ I canna

see,

I guess an’ fear!

The occasion of the poem was said to be Robert Burns overturning a mouse’s nest while plowing a field. Both Burns’s event and my event disturb a mouse’s life in November. His mouse I think lived, unlike the unfortunate end of the mouse in my house. Both Burns and I connected with the mouse on a compassionate level. We both meditated on our own mortality from a poor mouse’s life and fate. If Burns’ mouse lived after the scene, she will probably not survive the winter given the disruption of the nest.

Some

of Burns’ diction is a bit hard to grasp.

One can almost make out the Scots words but it would be helpful with

annotations of the Scottish. I don’t

know if the Scots used here is considered its own language, a slang, a dialect,

or a creole (probably a dialect), but it does mix English words with what I

take are Scottish versions of English words.

Some words seem to be purely Scotts Gaelic (“cranreuch,” “daimen”) and

some are English words transcribed from a Scottish dialect (“sleekit, cowrin,

tim'rous beastie”). Wikipedia has what

it calls an English translation of the original Scots, which I’ll post here.

Little, sleek, cowering,

timorous beast,

Oh, what a panic is in

your breast!

You need not start away

so hasty

With bickering prattle!

I would be loath to run

and chase you,

With murdering paddle!

I'm truly sorry man's dominion

Has broken Nature's

social union,

And justifies that ill

opinion

Which makes you startle

At me, your poor,

earth-born companion

And fellow mortal!

I doubt not, sometimes,

that you may thieve;

What then? Poor beast,

you must live!

An odd ear in twenty-four

sheaves

Is a small request;

I will get a blessing

with what is left,

And never miss it.

Your small house, too, in

ruin!

Its feeble walls the

winds are scattering!

And nothing now, to build

a new one,

Of coarse green foliage!

And bleak December's

winds ensuing,

Both bitter and piercing!

You saw the fields laid

bare and empty,

And weary winter coming

fast,

And cozy here, beneath

the blast,

You thought to dwell,

Till crash! The cruel

coulter passed

Out through your cell.

That small heap of leaves

and stubble,

Has cost you many a weary

nibble!

Now you are turned out,

for all your trouble,

Without house or holding,

To endure the winter's

sleety dribble,

And hoar-frost cold!

But Mouse, you are not

alone,

In proving foresight may

be vain:

The best-laid schemes of

mice and men

Go oft awry,

And leave us nothing but

grief and pain,

For promised joy!

Still you are blessed,

compared with me!

The present only touches

you:

But oh! I backward cast

my eye,

On prospects dreary!

And forward, though I

cannot see,

I guess and fear!

Like most translations of poetry, the beauty of the sounds of the language is lost in translation. Still it helps. Let’s analyze the poem, but I won’t go into the social and economic context of the times in which the poem was written. You can find that online if you want to. I’ll stick with the immediate poem.

There are eight stanzas of six lines of iambic tetrameter, each stanza with an unusual rhyme scheme of A/A/A/B/A/B. The fourth and sixth lines—the lines with the “B” rhyme—do not have eight syllables of a tetrameter line but either five syllables or four syllables. Why sometimes five syllables and other times four? I can’t see a pattern, so perhaps for oral articulation or perhaps just out of convenience. Nonetheless, I really like this stanza form.

The divisions of the poem I see in this way.

Stanzas

one and two provide situation of the event.

The poor mouse is in a panic, jabbering at the person who disrupted his

modest home, and scooting hastily about.

The second stanza I would say is the statement of the poem’s theme, the

breaking of some sort of an unspoken agreement between man and nature.

I’m truly sorry Man’s

dominion

Has broken Nature’s

social union,

An’ justifies that ill

opinion,

Which makes thee startle,

At me, thy poor,

earth-born companion,

An’ fellow-mortal!

The last two lines characterizing the mouse as a “poor, earth-born companion/An’ fellow-mortal” lift the little mouse, one of the most insignificant and despised of animals, to an equality with humanity.

Stanzas three through six characterize the impact to the mouse of the overturning of her nest. The mouse’s home is in ruin; she is now exposed to the winter elements; the plowed field has removed any source of food.

The seventh stanza connects the mouse’s futility with humanity’s, “In proving foresight may be vain,” giving us that great line that is truly a memorable quote, “The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men/Gang aft agley” (“the best-laid schemes of mice and men often go awry”).

The eighth and final stanza, Burns concludes with a distinction between man and beast. The mouse is blessed because, as an animal, he can only live in the present. He will move on from this event and forget about it. The poet, on the other hand has memory that will bring back sorrow every time he remembers such a catastrophe and, disrupted, will live in constant fear of the future. It is interesting that though not an overtly religious poem, a blessing is mentioned twice (third and eighth stanzas).

This is ultimately a nature poem, with man as an agent for disrupting nature for his purposes.

There are some great lines in this poem. I already mentioned “The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men/Gang aft agley” from stanza seven. I would say the first four lines are just so charming: “Wee, sleeket, cowran, tim’rous beastie,/O, what a panic’s in thy breastie!/Thou need na start awa sae hasty,/Wi’ bickerin brattle!” The first four lines of the fourth stanza are so musical: “Thy wee-bit housie, too, in ruin!/It’s silly wa’s the win’s are strewin!/An’ naething, now, to big a new ane,/O’ foggage green!” As are the first four lines of the eight stanza: “Still, thou art blest, compar’d wi’ me!/The present only toucheth thee:/But Och! I backward cast my e’e,/On prospects drear!”

Such

a lovely poem. You can hear it read in

both the Scot’s dialect and a modern translation on this clip.

What about my poor, little mousie? Well, though I feel for his plight, I’m not exactly to blame. He intruded my space, and he faced a natural enemy, Tiger! Behold the mighty hunter!

I

was wondering how I was going to get the mouse out. Tiger saved me the trouble.

Well done Tiger.

ReplyDeleteGod bless you all.

Thank you Victor!

DeleteI also think mice cute until they appear inside my house. We got our cat, Mr.Tumnus just for that purpose.

ReplyDeleteThanks Kelly. Cats do patrol for sneaky intruders. ;)

Delete