This is the third post in a series of St. John Henry Newman’s Apologia Pro Vita Sua.

You

can find Post #1 here.

Post

#2 here.

Chapter 2: History of My Religious Opinions from 1833 to 1839

Summary

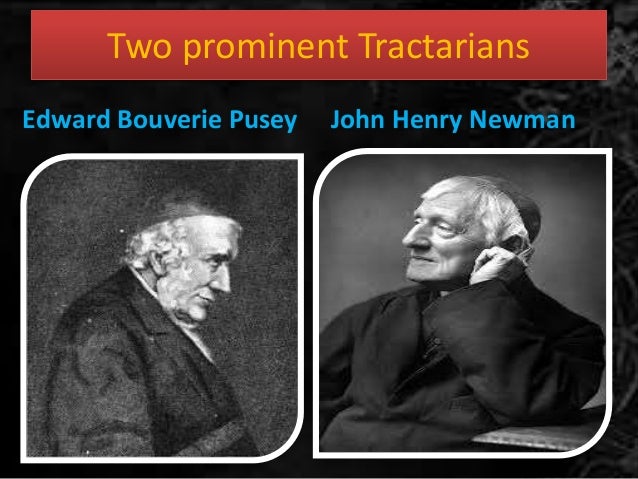

Chapter 2 provides the bulk of Newman’s output as a Protestant theologian. He makes it clear that he is still very much a committed Protestant but one of the key features of this period is Newman joining and supporting the Oxford Movement, a High Church theology that eventually evolved into Anglo-Catholicism and fought against the “Liberalism” of its day—that is the Evangelical Protestants and Low Church theology. Newman provides a description of two of the key members of his movement, Mr. Hugh Rose, John Keble, and Dr. Edward Pusey. What governs the development of this chapter are the series of Newman’s publications over these years. The most important of these publications were a series of tracts published by Newman, Pusey, and Keble that came to be known as the Tracts for the Times. The objective of the tracts was to present Anglicanism as the Via Media, that is, the middle way between Catholicism and Mainline Protestantism. The theology of the Oxford Movement was to recover the rich history of English Christianity from the Middle Ages but yet maintain a distinction from “Popish” Rome. One of Newman’s tracts, the last tract to be written, Tract 90, goes on to show that the 39 Articles central to the practice and faith of the Church of England are “compatible” with the Council of Trent, the Catholic Council in response to Protestantism, the central theological statement of the Counter-Reformation. Tract 90 caused a firestorm within the English Church from all sides that the Tracts had to be stopped and Newman forced to resign from the Oxford Movement.

Let me provide some Wikipedia links that might help you sort out this chapter.

###

How are you guys doing on this read? I was going back and forth in private mail with one of our members who is “struggling” with this read. I pointed out this is a tough read. There are several difficulties. First, it was written in the 19th century, so there's a style gap between Newman and us. Second, he's very intellectual, so there is a lot of knowledge that is assumed the reader to know. Third he's dealing with finer points of apologetics. Fourth, there's a historical time and place context. The history of the Anglican Church is not something we are generally taught. These definitely make reading this book difficult.

So, if you’re having trouble, just ask, either publicly or in a private mail. I would prefer publicly since that generates conversation. Also, just read along and just follow the conversation. Even if you don’t get it completely, I think you will get something out of this read. I believe I am getting it, though slowly, and so I think our schedule will be blown. But this is a famous work, and we will be satisfied to have read it. Plus, his conversion is coming up in the next couple of chapters, and that will be exciting. If all you get out of chapter 2 is the summary I posted above, I think that’s all you need to know to move on. So move on. It’s ok.

###

John

Henry Newman has the reputation of being one of the great prose stylist of the English

language. So far in the first two

chapters we probably have only seen that brilliance shine a few times, probably

because the dry facts of this person and his publications and that person and

his positions doesn’t make for inspired writing. At the beginning of chapter 2, Newman does

give us a portrait of Mr. Hugh Rose that allows his prose to excel. Let me quote these three paragraphs not so

much because they are very important to the chapter theme, but because they

show Newman’s skill as a writer. Perhaps

the key take-away is that Rose had been “severed” from the Oxford Movement and he

went on to die young.

To mention Mr. Hugh

Rose's name is to kindle in the minds of those who knew him a host of pleasant

and affectionate remembrances. He was the man above all others fitted by his

cast of mind and literary powers to make a stand, if a stand could be made,

against the calamity of the times. He was gifted with a high and large mind,

and a true sensibility of what was great and beautiful; he wrote with warmth

and energy; and he had a cool head and cautious judgment. He spent his strength

and shortened his life, Pro Ecclesia Dei, as he understood that sovereign idea.

Some years earlier he had been the first to give warning, I think from the

University Pulpit at Cambridge, of the perils to England which lay in the

biblical and theological speculations of Germany. The Reform agitation

followed, and the Whig Government came into power; and he anticipated in their

distribution of Church patronage the authoritative introduction of liberal

opinions into the country. He feared that by the Whig party a door would be

opened in England to the most grievous of heresies, which never could be closed

again. In order under such grave circumstances to unite Churchmen together, and

to make a front against the coming danger, he had in 1832 commenced the British

Magazine, and in the same year he came to Oxford in the summer term, in order

to beat up for writers for his publication; on that occasion I became known to

him through Mr. Palmer. His reputation and position came in aid of his obvious

fitness, in point of character and intellect, to become the centre of an

ecclesiastical movement, if such a movement were to depend on the action of a

party. His delicate health, his premature death, would have frustrated the

expectation, even though the new school of opinion had been more exactly thrown

into the shape of a party, than in fact was the case. But he zealously backed

up the first efforts of those who were principals in it; and, when he went

abroad to die, in 1838, he allowed me the solace of expressing my feelings of

attachment and gratitude to him by addressing him, in the dedication of a

volume of my Sermons, as the man, "who, when hearts were failing, bade us

stir up the gift that was in us, and betake ourselves to our true Mother."

But there were other reasons,

besides Mr. Rose's state of health, which hindered those who so much admired

him from availing themselves of his close co-operation in the coming fight.

United as both he and they were in the general scope of the Movement, they were

in discordance with each other from the first in their estimate of the means to

be adopted for attaining it. Mr. Rose had a position in the Church, a name, and

serious responsibilities; he had direct ecclesiastical superiors; he had

intimate relations with his own University, and a large clerical connexion

through the country. Froude and I were nobodies; with no characters to lose,

and no antecedents to fetter us. Rose could not go a-head across country, as

Froude had no scruples in doing. Froude was a bold rider, as on horseback, so

also in his speculations. After a long conversation with him on the logical

bearing of his principles, Mr. Rose said of him with quiet humour, that

"he did not seem to be afraid of inferences." It was simply the

truth; Froude had that strong hold of first principles, and that keen

perception of their value, that he was comparatively indifferent to the

revolutionary action which would attend on their application to a given state

of things; whereas in the thoughts of Rose, as a practical man, existing facts

had the precedence of every other idea, and the chief test of the soundness of

a line of policy lay in the consideration whether it would work. This was one

of the first questions, which, as it seemed to me, on every occasion occurred

to his mind. With Froude, Erastianism,—that is, the union (so he viewed it) of

Church and State,—was the parent, or if not the parent, the serviceable and

sufficient tool, of liberalism. Till that union was snapped, Christian doctrine

never could be safe; and, while he well knew how high and unselfish was the

temper of Mr. Rose, yet he used to apply to him an epithet, reproachful in his

own mouth;—Rose was a "conservative." By bad luck, I brought out this

word to Mr. Rose in a letter of my own, which I wrote to him in criticism of

something he had inserted in his Magazine: I got a vehement rebuke for my

pains, for though Rose pursued a conservative line, he had as high a disdain,

as Froude could have, of a worldly ambition, and an extreme sensitiveness of

such an imputation.

But there was another reason still, and a more elementary one, which severed Mr. Rose from the Oxford Movement. Living movements do not come of committees, nor are great ideas worked out through the post, even though it had been the penny post. This principle deeply penetrated both Froude and myself from the first, and recommended to us the course which things soon took spontaneously, and without set purpose of our own. Universities are the natural centres of intellectual movements. How could men act together, whatever was their zeal, unless they were united in a sort of individuality? Now, first, we had no unity of place. Mr. Rose was in Suffolk, Mr. Perceval in Surrey, Mr. Keble in Gloucestershire; Hurrell Froude had to go for his health to Barbadoes. Mr. Palmer was indeed in Oxford; this was an important advantage, and told well in the first months of the Movement;—but another condition, besides that of place, was required.

Try to read each sentence to yourself and let each sentence settle before you go to the next. Newman has such a wonderful rhythm. Notice how he uses couplets of adjectives and nouns: “pleasant and affectionate remembrances,” “cast of mind and literary powers,” “gifted with a high and large mind,” “of what was great and beautiful; he wrote with warmth and energy; and he had a cool head and cautious judgment.” It all sort of culminates with this powerful sentence: “He spent his strength and shortened his life…” Some writers love to write in twos, others in threes; Newman definitely in twos, which provides a very distinct rhythm.

Here’s another stylistic observation: he likes add little tags phrases (free modifying phrases) at the end of main clauses in order to balance the sentence. Like this: “His reputation and position came in aid of his obvious fitness, in point of character and intellect, to become the centre of an ecclesiastical movement, if such a movement were to depend on the action of a party.” “in point of character and intellect” is a modifying phrase of the main clause, and then he adds a tag “if such a movement were to depend on the action of a party” after subordinate clause, “to become the centre of an ecclesiastical movement.” One half of the sentence balances the other—again a sort of duple rhythm—and the repetition of the word “movement” from the subordinate clause echoes in the subsequent tag phrase, which seems to give an emphasis on that final beat of the rhythm.

Finally Newman is skillful in mixing long and short sentences. After a number of longish sentences, notice how the short staccato clauses of this section just bounces on the tongue: “Mr. Rose had a position in the Church, a name, and serious responsibilities; he had direct ecclesiastical superiors; he had intimate relations with his own University, and a large clerical connexion through the country. Froude and I were nobodies; with no characters to lose, and no antecedents to fetter us.” And none of these stylistic flourishes calls attention to itself. It probably came very natural to him, not giving it much thought. It’s just there for those that hear it and appreciate it.

###

Joseph

Commented:

I apologize that I've been a bit MIA, but I've had a busy couple of weeks. I find fascinating, from chapter one but fleshed out in chapter two, that the "religious liberalism" which Cardinal Newman was reacting against is pretty much the same as that we have today, just with different emphases. By and large, the critiques of the Oxford Movement seem to be that a Christianity which conforms itself to the fashions of the day eventually ceases to be Christianity. In broad strokes, we can see this pattern of argument repeated in today's debates over a slew of moral issues, and we can look back and see it as a forerunner to the Modernism of the early twentieth century. It certainly gives credence to the observation in Ecclesiastes that, "there is nothing new under the sun."

My

Reply:

The same thought occurred

to me too Joseph. However, I had to

scale back. The tension between those

that seek progressive advancement and those that seek to conserve is always

there going back to the nominalism of the Middle Ages, so it's not unusual for

Newman and those of his day to characterize a dichotomy between a

"liberal" faction and a "conservative" one. The question is always what is being

conserved and what is being advanced.

Here it seems that the Evangelical, Low Church is being called the

liberal while the Anglican High Church is the conservative. Intuitively it could have been just the

opposite for all I know. Why is the

Evangelical the liberal side? A lot

depends on the development of Anglican theology.

Here's what I know. When Henry VIII overturned the Catholic

faith, what he established was not too much different. But in short order with Queen Elizabeth, the

Puritan (forefathers to the Evangelicals) spirit started to rise sharply, and

with her successor James I it really began to dominate, so much so that when

his heir was going to be a Catholic king, the country went into Civil War, and

the Puritans won that war. England

became very much Low Church Puritan.

When the monarchy was re-instituted, it was more a return to Henry

VIII's Catholic-lite theology at the aristocratic level, but not so much at the

local level. Then there was another

civil war, more going back and forth until the Bloodless Revolution where

England pulled a king and queen from continental Europe who were very

Protestant. Now there was another

hundred years or so until Newman's time, where I don't exactly know which

theology was on top and which wasn't.

So now why would Anglo-Catholic be more conservative? As I reflected on it, I would have guessed the Low Church Evangelical was the conservative and those pushing closer toward Catholicism were the liberal. But I guess I am wrong. I just don’t have the nuanced understanding of the English religious scene of the 18th century that led to Newman.

Frances

Commented:

I’m not certain if this

contributes to the discussion but because it’s from Bishop Robert Barron’s Word

On Fire, I’d like to quote “What Is Liberalism”? from ‘’The Pivotal Players’’:

‘’When John Henry Newman battled theological ‘liberalism’ in his writings, he wasn’t engaging what we today mean by that word, in its political sense. Here’s how he defined it: ‘Liberalism is the doctrine that there is no positive truth in religion and that demonstration or formal logic is the only basis for any certitude. It teaches that all are to be tolerated and that revealed religion is not a truth, but a sentiment and a taste.’’

Peej

Commented:

Even though I haven’t started rereading yet, I do want to comment that the disregard of dogma is something I see in non-denominational churches today. One recent example is a sermon on Matthew 9–old wine in new wine skins—in a church in Parker, CO. The pastor used this verse to prove Biblically the principle of relevance. How remaining relevant and changing worship music can reach more people for Christ. But he never defined what is non-negotiable and what is dogma. This is a column built on quicksand.

My

Reply to Frances and Peej:

Those are both helpful

comments. What Peej is saying is along the lines of my assumption of Low Church

representing the Liberal side but frankly it doesn't seem to add up altogether.

The problem is that Newman was not clear as to what Liberalism refers to. I

think he assumed it from the context of his time. In the 1865 version, there is

a supplemental chapter called "Liberalism" where he states he was

asked to define it. Apparently others reading it made the same observation, and

so he had to add it. I have not read the chapter. Here is a link to the online

1865 publication.

The chapter on Liberalism

is the first of the supplemental material, under Note A. It looks like it's

only 14 pages. I'll try to read it tonight, but if anyone else wishes to,

please feel free to tell us what it says.

No comments:

Post a Comment