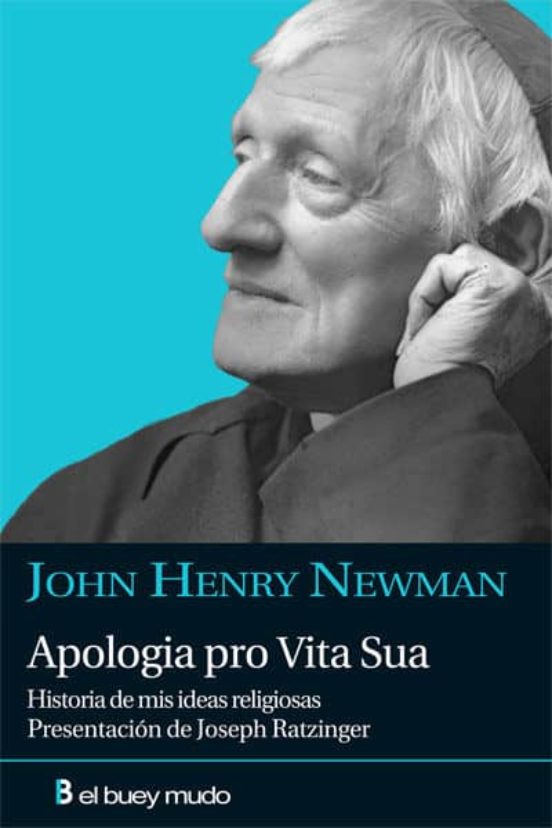

This is the second post in a series of St. John Henry Newman’s Apologia Pro Vita Sua. You can find Post #1 here.

Chapter 1. History of My Religious Opinions to the Year 1833

Summary

Newman divides his chapters by religious opinions to a certain age. In 1833 Newman would have been 32 years old, and he takes us through his adultescence, his university years, his ordination of Anglican clergyman, his assignment as parish vicar, and finally in 1833 a fateful trip on the Mediterranean where he spent time in the city of Rome. Newman mentions a number of people who were either influential to his development or important in his career. I won’t list them all but these I think were the most important: Thomas Scott, a historian, Joseph Milner, a Church historian, Dr. Whatley, professor at Oxford and future Archbishop of Dublin, Dr. Hawkins, vicar at St. Mary’s and a curate at Oxford, John Keble, a fellow professor (I think) at Oxford and perhaps his best friend at the time, Hurrell Foude, a student at Oxford and someone who had a great admiration for the Church of Rome. In 1832 Newman took a trip to the Mediterranean with Froude where he encountered a number of Catholic devotions and practices.

###

There were lots of good sections in this first chapter, and I won’t be able to highlight them all. Let me try to get the most important.

I

found his initial religious conversion to be very important.

When I was fifteen, (in the autumn of 1816,) a great change of thought took place in me. I fell under the influences of a definite Creed, and received into my intellect impressions of dogma, which, through God's mercy, have never been effaced or obscured. Above and beyond the conversations and sermons of the excellent man, long dead, the Rev. Walter Mayers, of Pembroke College, Oxford, who was the human means of this beginning of divine faith in me, was the effect of the books which he put into my hands, all of the school of Calvin. One of the first books I read was a work of Romaine's; I neither recollect the title nor the contents, except one doctrine, which of course I do not include among those which I believe to have come from a divine source, viz. the doctrine of final perseverance. I received it at once, and believed that the inward conversion of which I was conscious, (and of which I still am more certain than that I have hands and feet,) would last into the next life, and that I was elected to eternal glory. I have no consciousness that this belief had any tendency whatever to lead me to be careless about pleasing God. I retained it till the age of twenty-one, when it gradually faded away; but I believe that it had some influence on my opinions, in the direction of those childish imaginations which I have already mentioned, viz. in isolating me from the objects which surrounded me, in confirming me in my mistrust of the reality of material phenomena, and making me rest in the thought of two and two only absolute and luminously self-evident beings, myself and my Creator;—for while I considered myself predestined to salvation, my mind did not dwell upon others, as fancying them simply passed over, not predestined to eternal death. I only thought of the mercy to myself.

In this one paragraph he takes us from fifteen years old to twenty-one, which are rather critical years in the formation of a person. It is interesting he had his religious experience at the age of fifteen, which I cannot relate to. At fifteen I had no inclination for religion. My “religious experience” would happen in my forties. Was it a different time, or was Newman differently inclined? Well, he was definitely differently inclined than me, but there are today lots of adolescents and young men who are inclined to the religious life. Otherwise we wouldn’t have priests. But it was a different age as well. The 19th century saw a resurgence of faith after the decline and persecution of the Enlightenment. In many ways it paralleled the Romantic era. Just think of William Wordsworth and how religious he became as he grew older. I’m thinking that faith was in the air, and a bright, intellectually inclined young man would absorb it.

What is most interesting in that quoted paragraph is that Newman’s conversion was of a Calvinist for of Protestantism. This was not the form of Protestantism of his parents. Newman doesn’t exactly tell us what form of Christianity were his parents, but the Vélez biography I quoted in the Introduction states that Newman had been brought up in a “conventional Anglican family that attended Sunday services in church and held morning and evening prayers at home” (p. 11). Now I would imagine that in 1816 or prior “conventional Anglicanism” was not High Church Anglo Catholic, but I would be pretty sure it wasn’t Low Church Evangelical. It probably had many of the attributes of Catholicism since Newman mentions his dependence on angels and crossing himself. The sending off of children to boarding schools—which English families of means seemed to do—can create a divergence in cultural foundations between the generations. Here we see that Newman until the age of twenty-one had adhered to an Evangelical Calvinism, of which pre-destination and God’s control of everything is paramount.

I remember when Newman was canonized and I brought it up on a discussion board that he had been a convert to Catholicism. A number of Evangelical Protestants didn’t think much of it given that many are now used to Anglicans converting to Catholicism. So I looked it up back then to find he had started out as an Evangelical. I pointed it out and was an interesting observation for them.

###

Kerstin

Commented:

I found it fascinating

that from an early age on he was interested in matters of faith and the church.

Few teenagers read church histories voluntarily.

Also, he had a very keen sense of the material and immaterial. And then the

realization at the age of 15 that he would live a single/celibate life. This is

astounding. He was set apart from the beginning.

Christine

in Bo/Mass Commented:

I hate to admit it b/c I

know there is gold in this book, however it is really difficult to get into. It

reads like a journal, a more of a personal record than something written for

someone to internalize. Additionally all his influencers are exclusively male.

Can that be? I will have to double back to check if he mentions Our Mother.

Finding "home" at the Newman Society in college I read on mining for the gold I am sure is there somewhere.

My

Reply to Christine:

Oh Christine, he was big

on the Blessed Mother but it may be when he was a Catholic convert or close to

it. He's got sermons on the Marian dogmas.

Now as to women in his life, he was a bachelor, a priest, and a cardinal and I think the sexes didn't mix as much in Victorian times. I don't think he would have had as much interaction with women as we might think coming from today's world. He does mention his mother in that first chapter.

###

Newman

throughout Chapter 1 lays down markers

of Catholic doctrine that may not have been influential in this early period

but would I think come to bear upon his conversion in the future. We see him talk about the difference in

justification between Calvinism and Catholicism. We also see how Dr. Hawkins introduced him to

the importance of tradition in carrying the faith.

There is one other principle, which I gained from Dr. Hawkins, more directly bearing upon Catholicism, than any that I have mentioned; and that is the doctrine of Tradition. When I was an Undergraduate, I heard him preach in the University Pulpit his celebrated sermon on the subject, and recollect how long it appeared to me, though he was at that time a very striking preacher; but, when I read it and studied it as his gift, it made a most serious impression upon me. He does not go one step, I think, beyond the high Anglican doctrine, nay he does not reach it; but he does his work thoroughly, and his view was in him original, and his subject was a novel one at the time. He lays down a proposition, self-evident as soon as stated, to those who have at all examined the structure of Scripture, viz. that the sacred text was never intended to teach doctrine, but only to prove it, and that, if we would learn doctrine, we must have recourse to the formularies of the Church; for instance to the Catechism, and to the Creeds. He considers, that, after learning from them the doctrines of Christianity, the inquirer must verify them by Scripture.

What is interesting in what he says here is that one cannot develop doctrine from scripture alone but that doctrine came from the tradition of the apostles and was proven in scripture. And this makes a lot of sense. The Gospels are not a manual. They tell a story of events and sayings, but they do not put forth complete doctrine. You can “prove” lots of things by looking at a text, including contradictory things. The doctrine comes first, put out by the apostles and early church fathers, and then you go back to the story and show how to interpret the events in light of the doctrine. The tradition, in effect, shapes our understanding of the scriptures. I hope that makes sense. Pope Benedict XVI I believe has made the same observation.

###

One more highlight of Chapter 1. Toward 1827 Newman read a Christian Year by John Keble which apparently had great influence on his thought. He states that there were “two main intellectual truths which it brought home.”

The first of these was what may be called, in a large sense of the word, the Sacramental system; that is, the doctrine that material phenomena are both the types and the instruments of real things unseen,—a doctrine, which embraces in its fulness, not only what Anglicans, as well as Catholics, believe about Sacraments properly so called; but also the article of "the Communion of Saints;" and likewise the Mysteries of the faith. The connexion of this philosophy of religion with what is sometimes called "Berkeleyism" has been mentioned above; I knew little of Berkeley at this time except by name; nor have I ever studied him.

As

you can see, Newman is clearly moving toward High Anglicanism here. The notion of sacraments as being material

types of things unseen is exactly the Catholic understanding of the

sacraments. As to the second principle,

as I understand it, it rejects the notion that we come to belief not through a

judgment of the “probability” of facts, which can lead to skepticism, but

through faith and love.

I considered that Mr. Keble met this difficulty by ascribing the firmness of assent which we give to religious doctrine, not to the probabilities which introduced it, but to the living power of faith and love which accepted it. In matters of religion, he seemed to say, it is not merely probability which makes us intellectually certain, but probability as it is put to account by faith and love. It is faith and love which give to probability a force which it has not in itself. Faith and love are directed towards an Object; in the vision of that Object they live; it is that Object, received in faith and love, which renders it reasonable to take probability as sufficient for internal conviction. Thus the argument from Probability, in the matter of religion, became an argument from Personality, which in fact is one form of the argument from Authority.

Hopefully I captured that correctly. I’m not sure if this is a more Catholic notion but there is a strain of Protestantism that is much more utilitarian and of the physical world. The very notion of the Eucharist being the true body of Christ defies the immediate common sense and relies on personal faith in something beyond the senses. I think this is what Newman is alluding to here.

If I am correct on the understanding of the second principle, then both principles point to a continuity between the physical world and the spiritual, which is I believe one of the main differences between Catholics and Protestants. Protestants I think have a much sharper division—even a barrier—between the physical and spiritual that sometimes it seems they tend toward the gnostic.

###

I posted this quote as a “Notable Quote,” but it should be included in the book blog posts as well.

This

quote comes from the very first chapter, which details his beliefs and works up

to the age of thirty-two. The context of

the quote is while speaking of a particular mentor of his at Oxford, a Dr.

Hawkins. Most certainly an Anglican, Dr.

Hawkins had a very High Church theology.

He impressed this understanding upon the young Newman.

“The sacred text was

never intended to teach doctrine, but only to prove it, and that, if we would

learn doctrine, we must have recourse to the formularies of the Church.”

Now you can see how this understanding of scripture would be an undermining of Protestant rudiments. Certainly with this understanding, the Bible could not stand alone, and obviously you would need a “Church” to instruct you on the doctrine.

Newman

places himself under Dr. Hawkins between the years 1822 to 1825, which would

span his twenty-first to twenty-fourth years.

He would convert to Roman Catholicism in 1845 at the age of forty-four,

some twenty years later.

No comments:

Post a Comment