This is the fourth post in a series of St. John Henry Newman’s Apologia Pro Vita Sua.

You

can find Post #1 here.

Post

#2 here.

Post

#3 here.

I

finished reading his supplemental chapter on Liberalism, and frankly I still

don’t feel I definitively know what he means by the term. Still I think I’m closer because I think I’ve

cleared up a couple of confusions. From

what I gather, the Liberals are the Low Church Evangelicals but it was a particular

segment of Evangelicals. From the

“Liberalism” Notes:

When, in the beginning of the present century, not very long before my own time, after many years of moral and intellectual declension, the University of Oxford woke up to a sense of its duties, and began to reform itself, the first instruments of this change, to whose zeal and courage we all owe so much, were naturally thrown together for mutual support, against the numerous obstacles which lay in their path, and soon stood out in relief from the body of residents, who, though many of them men of talent themselves, cared little for the object which the others had at heart. These Reformers, as they may be called, were for some years members of scarcely more than three or four Colleges; and their own Colleges, as being under their direct influence, of course had the benefit of those stricter views of discipline and teaching, which they themselves were urging on the University... Thus was formed an intellectual circle or class in the University,—men, who felt they had a career before them, as soon as the pupils, whom they were forming, came into public life; men, whom non-residents, whether country parsons or preachers of the Low Church, on coming up from time to time to the old place, would look at, partly with admiration, partly with suspicion, as being an honour indeed to Oxford, but withal exposed to the temptation of ambitious views, and to the spiritual evils signified in what is called the "pride of reason."

So it sounds like the dispute was between factions at Oxford, between the High Church Anglican faction, of which Newman was a part, and a Low Church Evangelical faction, but that Evangelical faction was not necessarily in line with the Low Church pastoring that was in the English folk. If I got that correct, and I’m not 100% sure I do, then I can see the confusion. The Liberals were Low Church, but intellectual Low Church.

Newman

provides an actual definition of Liberalism:

Now by Liberalism I mean false liberty of thought, or the exercise of thought upon matters, in which, from the constitution of the human mind, thought cannot be brought to any successful issue, and therefore is out of place. Among such matters are first principles of whatever kind; and of these the most sacred and momentous are especially to be reckoned the truths of Revelation. Liberalism then is the mistake of subjecting to human judgment those revealed doctrines which are in their nature beyond and independent of it, and of claiming to determine on intrinsic grounds the truth and value of propositions which rest for their reception simply on the external authority of the Divine Word.

Now that we see the definition, and understand the factional conflict, I do think Joseph is right when he says, “In broad strokes, we can see this pattern of argument repeated in today's debates over a slew of moral issues, and we can look back and see it as a forerunner to the Modernism of the early twentieth century.” I think the “forerunner to the Modernism” goes back even further than this, but he is right when he says it is repeated in much the same pattern in today’s Church debates.

Toward the end of the chapter he provides a bullet list of 18 positions of the Liberals. Newman provides some exposition on each of the positions, which makes it too long to quote completely, so I’ll just list the eighteen without his expounding on them.

1. No religious tenet is

important, unless reason shows it to be so.

2. No one can believe

what he does not understand.

3. No theological

doctrine is any thing more than an opinion which happens to be held by bodies

of men.

4. It is dishonest in a

man to make an act of faith in what he has not had brought home to him by

actual proof.

5. It is immoral in a man

to believe more than he can spontaneously receive as being congenial to his

moral and mental nature.

6. No revealed doctrines

or precepts may reasonably stand in the way of scientific conclusions.

7. Christianity is

necessarily modified by the growth of civilization, and the exigencies of

times.

8. There is a system of

religion more simply true than Christianity as it has ever been received.

9. There is a right of

Private Judgment: that is, there is no existing authority on earth competent to

interfere with the liberty of individuals in reasoning and judging for

themselves about the Bible and its contents, as they severally please.

10. There are rights of

conscience such, that every one may lawfully advance a claim to profess and

teach what is false and wrong in matters, religious, social, and moral, provided

that to his private conscience it seems absolutely true and right.

11. There is no such

thing as a national or state conscience.

12. The civil power has

no positive duty, in a normal state of things, to maintain religious truth.

13. Utility and expedience

are the measure of political duty.

14. The Civil Power may

dispose of Church property without sacrilege.

15. The Civil Power has

the right of ecclesiastical jurisdiction and administration.

16. It is lawful to rise

in arms against legitimate princes.

17. The people are the

legitimate source of power.

18. Virtue is the child of knowledge, and vice of ignorance.

As you can see, most of them are very Liberal even by today’s standards. It is interesting that Newman states he never supported any of them “except No. 12, and perhaps No. 11, and partly No. 1.” In today’s the United States, I think number 17 would qualify as something to support, but otherwise I’m pretty much on board with Newman’s assessment.

I hope that clarifies now what Newman means by Liberalism.

###

Newman

articulates his theology of these years in three condensed points. I won’t quote the entire paragraphs that

outline those three points—it would be too much for here—but let me try to pull

summary quotes. Point #1:

1. First was the principle of dogma: my battle was with liberalism; by liberalism I mean the anti-dogmatic principle and its developments. This was the first point on which I was certain. Here I make a remark: persistence in a given belief is no sufficient test of its truth; but departure from it is at least a slur upon the man who has felt so certain about it. In proportion, then, as I had in 1832 a strong persuasion of the truth of opinions which I have since given up, so far a sort of guilt attaches to me, not only for that vain confidence, but for all the various proceedings which were the consequence of it. But under this first head I have the satisfaction of feeling that I have nothing to retract, and nothing to repent of. The main principle of the movement is as dear to me now, as it ever was. I have changed in many things: in this I have not.

Point #2

2. Secondly, I was confident in the truth of a certain definite religious teaching, based upon this foundation of dogma; viz. that there was a visible Church, with sacraments and rites which are the channels of invisible grace. I thought that this was the doctrine of Scripture, of the early Church, and of the Anglican Church. Here again, I have not changed in opinion; I am as certain now on this point as I was in 1833, and have never ceased to be certain. In 1834 and the following years I put this ecclesiastical doctrine on a broader basis, after reading Laud, Bramhall, and Stillingfleet and other Anglican divines on the one hand, and after prosecuting the study of the Fathers on the other; but the doctrine of 1833 was strengthened in me, not changed.

Point

#3:

3. But now, as to the third point on which I stood in 1833, and which I have utterly renounced and trampled upon since,—my then view of the Church of Rome;—I will speak about it as exactly as I can. When I was young, as I have said already, and after I was grown up, I thought the Pope to be Antichrist. At Christmas 1824-5 I preached a Sermon to that effect. But in 1827 I accepted eagerly the stanza in the Christian Year, which many people thought too charitable. "Speak gently of thy sister's fall." From the time that I knew Froude I got less and less bitter on the subject. I spoke (successively, but I cannot tell in what order or at what dates) of the Roman Church as being bound up with "the cause of Antichrist," as being one of the "many antichrists" foretold by St. John, as being influenced by "the spirit of Antichrist," and as having something "very Antichristian" or "unchristian" about her. From my boyhood and in 1824 I considered, after Protestant authorities, that St. Gregory I. about A.D. 600 was the first Pope that was Antichrist, though, in spite of this, he was also a great and holy man; but in 1832-3 I thought the Church of Rome was bound up with the cause of Antichrist by the Council of Trent.

I think that captures the three points, but if you want the full development of each point you will have to turn to the text. Actually about ten pages later, Newman, in identifying his position as the Via Media, summarizes them himself:

Lest I should be

misunderstood, let me observe that this hesitation about the validity of the

theory of the Via Media implied no

doubt of the three fundamental points on which it was based, as I have

described them above, dogma, the sacramental system, and anti-Romanism.

So I think one can look at the first two points as Catholic-lite, but the third as strongly anti-Catholic.

###

Notable Quote: What the Church Needs by John Henry Newman

Here

is another distinctive quote by this wonderful prose writer.

“What we need at present for our Church's well-being, is not invention, nor originality, nor sagacity, nor even learning in our divines, at least in the first place, though all gifts of God are in a measure needed, and never can be unseasonable when used religiously, but we need peculiarly a sound judgment, patient thought, discrimination, a comprehensive mind, an abstinence from all private fancies and caprices and personal tastes,—in a word, Divine Wisdom."

In the first main clause he provides a list of negatives (“not, nor, etc.) of what the Church doesn’t need. Then he pauses with a subordinate clause qualifying those negatives before he gives a second main clause providing a list of what it does need, including an “abstinence” which is another form of negation. Then he tops it off with a summation, “Divine Wisdom.” That is just so beautiful.

###

Now

that we have an understanding of what Newman means by Liberal, I think this key

statement can be re-looked at:

Lest I should be misunderstood, let me observe that this hesitation about the validity of the theory of the Via Media implied no doubt of the three fundamental points on which it was based, as I have described them above, dogma, the sacramental system, and anti-Romanism.

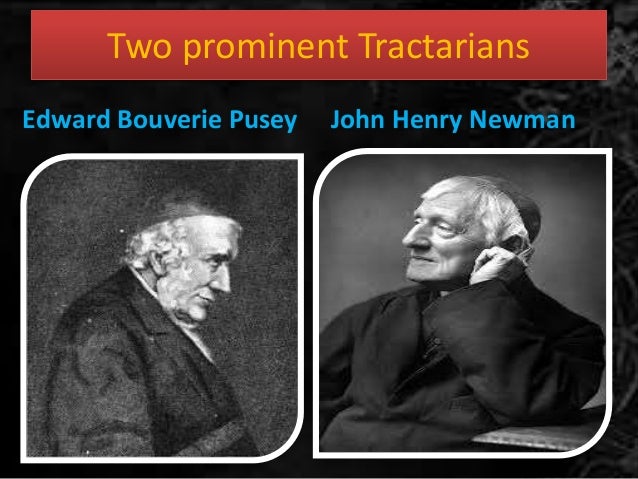

Of the three fundamental points on which he defines the Via Media, which is supposed to define High Church Anglicanism, each is in counter-distinction to three opposing religions. That the Via Media rests on defined dogma is in counter-distinction to Liberal Low Church Evangelicalism; that the Via Media contains a sacramental system is in counter-distinction to traditional Low Church Evangelicalism; and that the Via Media is anti-Romanism stands in opposition to the Roman Catholic Church.

Unless anyone else wants to pursue discussion of chapter 2, I think we have captured the gist of it. If we had more time, we could look more closely at Tract 90, but we are already behind, and I think that summation just now suffices for our book club purposes.

###

I’ve

been meaning to mention this, and perhaps here is a good place to mention

it. I don’t know if you realize, because

I didn’t realize for the longest time, the term “Roman Catholic Church” is not

any official title or name. The English

assigned it the “Roman Catholic Church” to distinguish it from their

“Anglo-Catholic Church.” There is no

Latin term that identifies the Catholic Church as the Roman Catholic Church, or

French, or Italian, or German, or any other language but English. Everyone else uses simply, “The Catholic

Church.” I was surprised to learn that

because it is so common in English. I

personally try to resist using Roman Catholic, and just go with Catholic. In my mind, by qualifying Catholic with Roman

is tending toward the pejorative, and even if not intended to be pejorative, it

is a diminishing of the supremacy of the Catholic Church. “Catholic” means “universal,” and by giving

it a qualifier is to diminish her universality.

I try not to do it, though sometimes it can’t be helped.