Following up on my 2021 Reads post, let me walk you through my short story reads for the year. I didn’t realize just how good a year in short story reading it was until I put this together. Of the nineteen stories, I ranked only one as a “Dud,” five ranked “Ordinary,” eight ranked “Good,” and four ranked “Excellent.” That’s twelve stories that were good or excellent. As you look through the list, you can see that most were well known authors. Here’s how I ranked the stories.

Exceptional

“The

Presence,” by Caroline Gordon.

“Swept

Away,” by T. Coraghessan Boyle.

“Gods,” by Vladimir Nabokov.

“A Night in the Poorhouse,” a short story by Isaac Bashevis Singer.

Good

“Nimram,”

by John Gardner.

“Screwball,”

by William Baer.

“Wintry

Peacock,” by D. H. Lawrence.

“The

Manager of ‘The Kremlin,’” by Evelyn Waugh.

“A

Snowy Night on West Forty-Ninth Street,” by Maeve Brennan.

“The

Unrest-Cure,” by Saki (H.H. Munro).

“The

Curse,” by Andre Dubus.

“Shower of Gold,” a short story by Eudora Welty.

Ordinary

“Baptism,”

a (Don Camillio) short story by Giovanni Guareschi.

“The

Coffee-House of Surat,” a short story by Leo Tolstoy.

“Acts

of God,” a short story by Ellen Gilchrist.

“In the Walled City,” a short story by Sewart O’Nan.

“Dead

Man’s Path,” a short story by Chinua Achebe.

“The Sea Change,” a short story by Ernest Hemingway.

Duds

“Granted

Wishes: Unpopular Girl,” a short story by Thomas Berger.

###

Let me provide you a one paragraph summary and comment on each of the stories. First the one Dud and then the five Ordinary stories. “D” stands for Dud, “O” for Ordinary, “G” for Good.

⁂

“Granted Wishes: Unpopular Girl” by

Thomas Berger. (D)

Janice, an attractive but socially inept and dull young lady, tries to learn how to be more popular. Through a scheme she gets rich and all of sudden is very popular. That’s it! Don’t bother.

⁂

“Baptism” by Giovanni Guareschi.

(O)

The communist mayor, Don Camillio’s arch nemesis, brings his newly born infant to the church to be baptized. And then the fun begins. Charming as always but too quickly resolved.

⁂

“The Coffee-House of Surat” by Leo Tolstoy. (O)

From Wikipedia: “The story takes place in Surat, India, where a single follower of Judaism, Hinduism, Protestantism, Catholicism, and Islam argue with each other about the true path to salvation, while a quiet Chinese man looks on without saying anything, the piece concluding when the followers turn to him and ask his opinion.”

The arguments center on which is the true religion and the nature of the sun as derived from their theologies. The Chinese man, speaking for Tolstoy, argues that pride causes error and the sun lights up the whole world, which then is the natural religion. You can read this story online here:

The story was overly didactic and the characters just stand-ins for their religions.

⁂

“Acts of God” by Ellen Gilchrist. (O)

An elderly married couple living in New Orleans, in love since grade school and still in their eighties, despite being warned of the oncoming hurricane Katrina, flee their house to get away from their sitter in a sort of mock elopement and have to face the consequences of the hurricane. Interesting characters but too underdeveloped a story. That “acts” in the title is plural carries significance.

⁂

“Dead Man’s Path,” Chinua Achebe. (O)

Michael Obi is appointed headmaster of a school in a traditional African community. Soon he and his wife intend to implement new, progressive approaches to schooling. On his first attempt he gets a backlash. I wish there was more to this story. The material is greater than just a few pages of narrative.

You can read the story online here.

And read a fairly detailed analysis of the story here

⁂

“The Sea Change” by Ernest Hemingway.

(O)

A man and a woman, lovers, are at a café arguing over something the woman won’t do. We learn that she will not break off a relationship with another woman. Once the arguing is over and she leaves him, the sea change is as much about the man now as is about the woman. Well written but not very deep and overly sensationalistic. Critics seem to see more to it than I do, but I think it’s because its an early reference in literature to lesbianism.

You can read an analysis of the story here and another analysis here.

###

Now here are the eight “Good” ranked stories. I’ll give you the same summary and comment paragraph but for these stories I’m going to include a short snippet from the story.

⁂

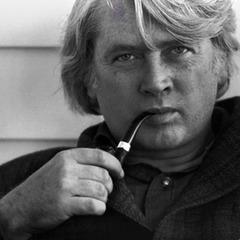

“Nimram” by John Gardner. (G)

A famous, middle-aged classical music conductor who has enjoyed and is still enjoying a good life with hardly any misfortunes meets on an airplane a teenage girl with crutches. Both are traveling to Chicago, he to conduct the symphony and she to attend. On the flight he learns that she is terminally ill but has a profound belief in God. It’s a well written story that falls just short of excellent. There seemed to be a complexity missing that could have elevated the theme a bit more.

You can read about John Gardner at his Wikipedia entry here.

And there is a great article where Gardner is asked about his writing and other contemporary writers. Gardner doesn’t pull punches. Here.

Here

is an excerpt from the story, an exposition of Benjamin Nimram.

He was not a man who had ever given thought to whether or not his opinions of himself and his effect on the world were inflated. He was a musician simply, or not so simply; an interpreter of Mahler and Bruckner, Sibelius and Nielsen—much as his wife Arline, buying him clothes, transforming his Beethoven frown to his now just as famous bright smile, brushing her lips across his cheek as he plunged (always hurrying) toward sleep, was the dutiful and faithful interpreter of Benjamin Nimram. His life was sufficient, a joy to him, in fact. One might have thought of it—and so Nimram himself thought of it, in certain rare moods—as one resounding success after another. He had conducted every major symphony in the world, had been granted by Toscanini’s daughters the privilege of studying their father’s scores, treasure-horde of the old man’s secrets; he could count among his closest friends some of the greatest musicians of his time. He had so often been called a genius by critics everywhere that he had come to take it for granted that he was indeed just that—“just that” in both senses, exactly that and merely that: a fortunate accident, a man supremely lucky. Had he been born with an ear just a little less exact, a personality more easily ruffled, dexterity less precise, or some physical weakness—a heart too feeble for the demands he made of it, or arthritis, the plague of so many conductors—he would still, no doubt, have been a symphony man, but his ambition would have been checked a little, his ideas of self-fulfillment scaled down. Whatever fate had dealt him he would have learned, no doubt, to put up with, guarding his chips. But Nimram had been dealt all high cards, and he knew it. He revelled in his fortune, sprawling when he sat, his big-boned fingers splayed wide on his belly like a man who’s just had dinner, his spirit as playful as a child’s for all the gray at his temples, all his middle-aged bulk and weight—packed muscle, all of it—a man too much enjoying himself to have time for scorn or for fretting over whether or not he was getting his due, which, anyway, he was. He was one of the elect. He sailed through the world like a white yacht jubilant with flags.

I have always liked John Gardner’s writing. Make sure you read his novel, Grendel some day.

⁂

“Screwball” by William Baer. (G)

A young man who is a major league pitcher has an incredible, career year dominating the league and almost singlehandedly leading his team to winning the World Series. And then in the off season he suddenly dies, and his best friend, a police detective, investigates the mystery of how he died and how his friend developed that screwball pitch that dominated the league. In the process he wins the heart of the deceased pitcher’s sister. A really fine story but it missed the top mark because it was too formulaic of a detective novel.

You can read about William Baer here. And he had an “Exceptional” short story (“Times Square”) in my last year’s reads. You can read about it here.

Here are the wonderful opening paragraphs of “Screwball.”

It was the fourth and

final game of the World Series: Ricky Kight, with the look of a hired 6’4”

gunslinger, had walked in from the bullpen with a 1-0 lead in the eighth and

struck out the side. Then he whiffed Gonzales to start off the bottom of the

ninth, got Marshall on a broken-bat blooper to short left, and was now facing

down Ramirez with a 2-2 count.

“Will he send,” one of

the announcers wondered rhetorically, “the juice, the split curve, or his nasty

screwgie?”

Every baseball fan in

America, of course, was wondering exactly the same thing as Ricky took the

sign, went into his windup, and then, with that peculiar, idiosyncratic, and

inexplicably odd arm motion, threw what Mathewson used to call a “fadeaway,” and

what Carl Hubbell later called a “screwball,” and what the umpire called a

“strike!” It was over. The Yankees had swept the World Series for the ninth

time. The stadium erupted, the players went nuts, and Keith hit the pause

button on his laptop.

That was eight months

ago, when Ricky Kight, who was Keith’s old high school friend and teammate, had

capped off an absolutely unprecedented season (19-0, 1.34 ERA) with an

absolutely unprecedented World Series: winning a first-game shutout and then

closing down the last three games with an efficiency and intimidation that

reminded everyone in America of Mariano Rivera at his best. Then, a month

later, his career was suddenly over. He was helping a friend move a piano,

smashed his right shoulder, and damaged his rotator cuff (not irreparably), his

scapular, his tendons, his muscles, and, far more severely, his radial nerve.

At first, given the “piano” aspect of the story, it almost seemed like a joke,

or a hoax, and it got lots of clever headlines in the Post and all over the

web, but it was definitely no joke, and even Ricky’s always-optimistic

high-powered sports agent, Mike Rodgers, had eventually accepted and announced

the terminality of the fact at a tumultuous press conference with a kind of

stunned disbelieving bemusement.

But now, even that, even the shocking career-ending injury seemed like just another biographical quirk, just another strange baseball-history anecdote or footnote, because Ricky was dead, dying in a head-on just two months ago after a charity event in Atlantic City, having stopped off at Barnegat Light on the way home to Morristown, to stare at the ocean, which had always given him a sense of inexplicable serenity, before getting himself smacked by some forty-year-old unemployed drunk driver (0.33 blood/alcohol level) on Long Beach Boulevard.

And so we enter the mystery of Ricky’s career and death.

⁂

“Wintry Peacock” by D. H. Lawrence. (G)

While

on a walk in the country, the male unnamed narrator is stopped by a farm woman

who wants him to translate a letter written in French. The letter is addressed to her husband who

has been in France for the World War, is expected home that evening. The narrator reads the letter and realizes

it’s from a young Belgian woman who the husband got pregnant. Meanwhile the woman‘s relationship to the

farm peacock puts in perspective the triangular relationship the narrator is

faced with. The next day the narrator

happens back on the farm and meets the husband.

It almost ranked excellent but the characters are all unlikable and it

seems to end on a malicious note. You

can read the story online here: and listen to it being read here on YouTube:

Here is an excerpt where the farm woman gives the passing narrator the letter to translate.

'It's a letter to my

husband,' she said, still scrutinizing.

I looked at her, and

didn't quite realize. She looked too far into me, my wits were gone. She

glanced round. Then she looked at me shrewdly. She drew a letter from her

pocket, and handed it to me. It was addressed from France to Lance-Corporal

Goyte, at Tible. I took out the letter and began to read it, as mere words.

'Mon cher Alfred'--it might have been a bit of a torn newspaper. So I followed

the script: the trite phrases of a letter from a French-speaking girl to an

English soldier. 'I think of you always, always. Do you think sometimes of me?'

And then I vaguely realized that I was reading a man's private correspondence.

And yet, how could one consider these trivial, facile French phrases private!

Nothing more trite and vulgar in the world, than such a love-letter--no

newspaper more obvious.

Therefore I read with a

callous heart the effusions of the Belgian damsel. But then I gathered my

attention. For the letter went on, 'Notre cher petit bebe--our dear little baby

was born a week ago. Almost I died, knowing you were far away, and perhaps

forgetting the fruit of our perfect love. But the child comforted me. He has

the smiling eyes and virile air of his English father. I pray to the Mother of

Jesus to send me the dear father of my child, that I may see him with my child

in his arms, and that we may be united in holy family love. Ah, my Alfred, can

I tell you how I miss you, how I weep for you. My thoughts are with you always,

I think of nothing but you, I live for nothing but you and our dear baby. If

you do not come back to me soon, I shall die, and our child will die. But no,

you cannot come back to me. But I can come to you, come to England with our

child. If you do not wish to present me to your good mother and father, you can

meet me in some town, some city, for I shall be so frightened to be alone in

England with my child, and no one to take care of us. Yet I must come to you, I

must bring my child, my little Alfred to his father, the big, beautiful Alfred

that I love so much. Oh, write and tell me where I shall come. I have some

money, I am not a penniless creature. I have money for myself and my dear baby--'

I read to the end. It was

signed: 'Your very happy and still more unhappy Elise.' I suppose I must have

been smiling.

'I can see it makes you

laugh,' said Mrs. Goyte, sardonically. I looked up at her.

'It's a love-letter, I

know that,' she said. 'There's too many "Alfreds" in it.'

'One too many,' I said.

'Oh, yes--And what does

she say--Eliza? We know her name's Eliza, that's another thing.' She grimaced a

little, looking up at me with a mocking laugh.

The success of this story hinges on the psychological depth of the farm woman, Mrs. Goyte. It’s symbolically drawn through her relationship with the peacock,

⁂

“The Manager of ‘The Kremlin’” by

Evelyn Waugh. (G)

Boris, the manager of a Russian restaurant, tells the narrator his story of how he came to manage “The Kremlin,” a restaurant in Paris. He had opposed the Bolshevik takeover of Russia, fighting alongside a Frenchman. Having made his way to America and then to Paris with almost no money, he decides to spend all that he had on one expensive lunch. There he reconnects with the Frenchman who then gives him the opportunity to manage a restaurant. But it is the loss of his country that so effects Boris. Well written as everything by Waugh but seems to be missing more depth.

The English newspaper The Guardian ranked it as having one of the top ten memorable meal scenes in literature and they give it a one paragraph synopsis here.

You can hear the story read here.

Here

is that memorable meal scene and the afterwards.

He ate fresh caviar and ortolansan porto and crepes suzettes; he drank a bottle of

vintage claret and a glass of very fine

champagne, and he examined several boxes of cigars before he found one in

perfect condition.

When he had finished, he

asked for his bill. It was 260

francs. He gave the waiter a tip of 26

francs and 4 francs to the man at the door who had his hat and kitbag. His taxi cost 7 francs.

Half a minute later he

stood on the kerb with exactly 3 francs in the world. But it had been a magnificent lunch, and he

did not regret it.

As he stood there,

meditating what he could do, his arm was suddenly taken from behind, and

turning he saw a smartly dressed Frenchman, who had evidently just left the

restaurant. It was his friend the

military attaché.

“I was sitting at the

table behind you,” he said. “You never

noticed me, you were so intent on your food.”

“It is probably my last

meal for some time,” Boris explained, and his friend laughed at what he took to

be a joke.

They walked up the street

together, talking rapidly. The Frenchman

described how he had left the army when his time of service was up, and was now

a director of a prosperous motor business.

“And you, too,” he

said. “I am delighted to see that you

also have been doing well.”

“Doing well? At the moment I have exactly three francs in

the world.”

“My dear fellow, people

with three francs in the world do not eat caviare at Larne.”

Then for the first time he noticed Boris’s frayed clothes. He had only known him in a war-worn uniform and it seemed natural at first to find him dressed as he was.

A story first and foremost has to be a story, not a hum drum recapitulation of mundane events. A man spends everything he has on one meal and leaves the future to Providence. Now that’s a story.

⁂

“A Snowy Night on West Forty-Ninth Street” by Maeve Brennan. (G)

A woman, a stand-in for the author, sits at her usual restaurant in midtown Manhattan for dinner and comradery as shy typically does. On this night there is a snow storm, so the attendance is less and those that are there have a particular isolation. Through the woman’s point of view we dwell on the other character’s actions. Of the characters, the most central are an elderly lady, Mrs. Dolan, who seems to have an attraction for a French business man named Michel, who doesn’t really return the interest. The movement of the story is toward greater isolation despite the attempts to connect with others. Though this story captures the scene and characters well, and has an evocative tone, it ends without any real conclusion. But a good story.

If you have a subscription to the New Yorker you can read the short story online here.

Since this story has a very biographical seed, you can read about Maeve Brennan here. Brennan was a long time contributor to the New Yorker magazine, one of the most finely polished of literary magazines. She was known there as “The Long-Winded Lady,” and you can read about her tenure and work, the seeds of this story, and her life in this essay, “New introduction to Maeve Brennan’s‘The Long-Winded Lady’.

Here’s

a snippet of Betty who is new to New York City and new to snow coming in to the restaurant later

than the rest.

“Where’s everybody?” she

cried. “Where’s Mees Katie?” She sat up at the bar and Leo poured a

Perrier for her.

“I’m celebrating, Leo,:

she said. “This is my first

snowstorm. The office let us off at

three o’clock, and I walked round and round and round, all by myself, celebrating

all by myself, and then I went home and made dinner, but I got so excited

thinking about the snow I just had to come out again and thought I come here

and see Mees Katie. I thought there’d be

thousands of people here. Oh, I wish it

would snow for weeks and weeks. I just

can’t bare for it to end. But after

today I’m beginning to think New Yorkers never really enjoy themselves. Nobody seemed to be enjoying the snow. I never saw such people. All they could think about was getting

home. Wouldn’t you think a storm like

this would wake everybody up? But all it

does is put them to sleep. Such people.”

“It does not put me to

sleep, Betty,” Leo said in his deliberate way.

“I wish it would snow for

a year,” Betty said.

It will take something

warmer than a snowstorm to put me to sleep, Betty,” Leo said.

Betty laughed

self-consciously and looked at Mrs. Dolan.

“Michel is a bad boy

tonight, Betty,” Leo said, and he also looked at Mrs. Dolan. “He told this lady he’d be back in ten

minutes and it has been twenty.”

“Nearly half and hour,”

Mrs. Dolan said disgustedly. “Nearly

half an hour.”

“He’ll be back,” Betty said. “Michel always comes back, doesn’t he Leo?”

You get the sense. It’s mostly a mood piece that captures a time and place.

⁂

“The Unrest-Cure” by Saki (H.H.

Munro). (G)

J.P. Huddle, an aristocratic Edwardian man of such fixed routine, tells his friend while on a train that he has reached a point in his life that he gets immensely irritated when something doesn’t follow regularity. His friend suggests that Huddle go on an “unrest-cure,” the opposite of a resting convalescence. Over hearing is Clovis, an impish, reoccurring character in several of Saki’s stories, who then sets out to liven Huddle’s life by contriving a spoof plot to bring about a holocaust right in Huddle’s house. Huddle is certainly shaken out of his daily practice. He typifies the upper class of Edwardian times. The story is great play but it seems to lose transcendence in the extended carrying out of the narrative. Still a sharp and concise story as typical of Saki.

You

can read the story here, read a short summary in Wikipedia under Saki’s entry here, and listen to it being read on YouTube.

Here

is Huddle describing his rut and his friend proposing the “unrest-cure.”

"I don't know how it

is," he told his friend, "I'm not much over forty, but I seem to have

settled down into a deep groove of elderly middle-age. My sister shows the same

tendency. We like everything to be exactly in its accustomed place; we like

things to happen exactly at their appointed times; we like everything to be

usual, orderly, punctual, methodical, to a hair's breadth, to a minute. It

distresses and upsets us if it is not so. For instance, to take a very trifling

matter, a thrush has built its nest year after year in the catkin-tree on the

lawn; this year, for no obvious reason, it is building in the ivy on the garden

wall. We have said very little about it, but I think we both feel that the

change is unnecessary, and just a little irritating."

"Perhaps," said

the friend, "it is a different thrush."

"We have suspected

that," said J. P. Huddle, "and I think it gives us even more cause

for annoyance. We don't feel that we want a change of thrush at our time of

life; and yet, as I have said, we have scarcely reached an age when these

things should make themselves seriously felt."

"What you

want," said the friend, "is an Unrest-cure."

"An Unrest-cure?

I've never heard of such a thing."

"You've heard of Rest-cures for people who've broken down under stress of too much worry and strenuous living; well, you're suffering from overmuch repose and placidity, and you need the opposite kind of treatment."

Huddle is quite a character. Saki is excellent at delineating idiosyncratic characters in the shortest space.

⁂

“The Curse” by Andre Dubus. (G)

Mitchell, a middle-aged bartender, witnesses the gang rape of a young lady by five drugged up bikers at his bar just before closing. He had tried to call the police while it was happening but he was restrained. That evening and into the next day he feels nothing but shame at his inability to stop the situation. The curse he feels upon him is the memory of the young lady’s screams. The story captures the situation and the working class characters well, but seems to lack anything transcendent beyond Mitch’s emotions.

Here

is the aftermath of the rape, but first a flashback to just prior.

Then the door opened and

the girl walked in from the night, a girl he had never seen, and she crossed

the floor toward Mitchell. He stepped forward to tell her she had missed last

call, but before he spoke she asked for change for the cigarette machine. She

was young, he guessed nineteen to twenty-one, and deeply tanned and had dark

hair. She was sober and wore jeans and a dark blue tee shirt. He gave her the

quarters but she was standing between two of the men and she did not get to the

machine.

When it was over and she

lay crying on the cleared circle of floor, he left the bar and picked up the

jeans and tee shirt beside her and crouched and handed them to her. She did not

look at him. She lay the clothes across her breasts and what Mitchell thought

of now as her wound. He left her and dialed 911, then Bob’s number. He woke up

Bob. Then he picked up her sneakers from the floor and placed them beside her

and squatted near her face, her crying. He wanted to speak to her and touch

her, hold a hand or press her brow, but he could not.

The emotionless sentences fills the scene with tension.

⁂

“Shower of Gold” by Eudora Welty. (G)

The story of Snowdie, an

albino woman in a small town in Mississippi, first birthing and then raising a

pair of twin boys alone because her wayward husband, King MacLain, has left

her. Then he returns to only abandon her

again. Her story is told through the

gossipy, southern dialect of the narrator, Katie Rainy, Snowdie’s

neighbor. The key to this story is realizing

it’s a gossip’s tale. The story ends

without a strong denouement, which unfortunately lowers its rating. Perhaps that is unfair since this story is

part of an interlocking series of stories about the fictional town of Morgana,

Mississippi, collected as The Golden

Apples.

You can read about The Golden Apples collection in its

Wikipedia entry here. You can also read summaries of Welty's collected stories

here and about the various characters in the story collection

here .

Here is Katie Rainy describing a pregnant Snowdie

after her husband left her.

Snowdie

kept just as bright and brave, she didn’t seem to give in. She must have had her thoughts and they must

have been one of two things. One that he

was dead—then why did her face have that glow?

It had a glow—and the other that he left her and meant it. And like people said, if she smiled then, she was clear out of reach. I didn’t know if I liked the glow. Why didn’t she rage and storm a little—to me,

anyway, just Mrs. Rainy? The Hudsons all

hold themselves in. But it didn’t seem

to me, running in and out the way I was, that Snowdie had ever got a real good

look at life, maybe. Maybe from the

beginning. Maybe she just doesn’t know

the extent. Not the kind of look I got, and away back

when I was twelve year old or so. Like

something was put to my eye.

She

just went on keeping house, and getting fairly big with what I told you already

was twins, and she seemed to settle into her content. Like a little white kitty in a basket, making

you wonder if she just mightn’t put up her paw and scratch, if anything was,

after all, to come near. At her house it

was like Sunday even in the mornings, every day, in that cleaned-up way. She was taking a joy in her fresh untracked

rooms and that dark, quiet, real quiet hall that runs through her house. And I love Snowdie. I love her.

Except

none of us felt very close to her all

the while. I’ll tell you what it was,

what made her different. It was not

waiting any more, except where the babies waited, and that’s not but one story. We were mad at her and protecting her all at

once, when we couldn’t be close to her.

Wow, that is a fantastic description and fantastic

monologue. Welty is an amazing story

teller.

The four “Excellent” rated stories will have their

own post where I will disclose the winner for this year. Stay tuned.

No comments:

Post a Comment