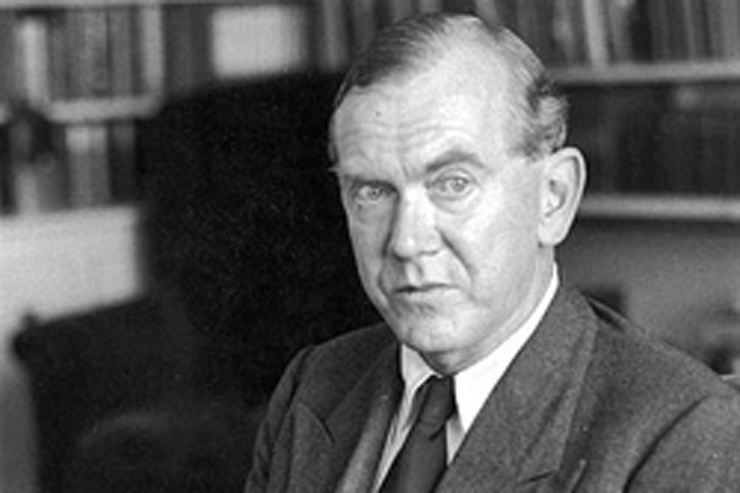

This is the fifth and last post on my reading of Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory.

You

can read Post #1 here.

Post#2

here.

Post

#3 here.

Post

#4 here.

Parts 3 and 4

Summary

Chapter 1

The priest is in safe territory now staying at the house of a married German, Lutheran couple, who though they disapprove of Catholicism give the priest safe haven. In town, the priest hears confessions, celebrates Mass, and performs baptisms. He finds this safe life uncomfortable. Just as he’s to depart for another city he meets the mestizo again, who implores him to go with him back into dangerous territory because the criminal gringo is dying and needs a final confession. Fully realizing that this is a trap, the whisky priest decides to go.

Chapter 2

The priest and mestizo come to a group of huts, and the mestizo leads him into one where the gringo is actually there and dying. The priest tries to induce a confession from the gringo who only tells him to go away and to take his knife. The priest insists on a confession, but the gringo dies.

Chapter 3

Suddenly the lieutenant comes into the doorway and makes himself known. The priest realizes it has been a trap. He offers no resistance and in a way is actually glad his running is over. The lieutenant is to take him back to the town of his police station to stand trial for treason, but it is raining and so decides to wait for the rain to end. While waiting the lieutenant and the priest sit by candlelight and talk over their views of Catholicism. The priest’s humility seems to touch the lieutenant and he appears to feel a certain remorse, and asks the priest for a request. The priest just wants to say his last confession and be absolved of his sins. The storm ends and they get on horses for the trip.

Chapter 4

Back at town, the lieutenant goes to Padre Jose’s house to bring him to the police station to hear the whisky priest’s confession. Padre Jose is willing to go but his wife refuses to let him go. The lieutenant goes back to the dark cell where the priest has been placed and tells him he could not get him his confessor. But he does give him one last bottle of brandy to pass the night. Alone and drunk he goes through his last sins attempting at repentance, but he thinks of his daughter and the love he feels for her. He has a dream of being at an altar and partaking a feast where he sees the girl, Coral, who taps out Morse code. He awakes and it is morning and he feels the regret of not accomplishing more as a priest.

Part 4

Captain and Mrs. Fellows are in a hotel talking about going home. Mrs. Fellows is sick as usual but wants to return to their home while Captain Fellows does not want to. From the conversation we surmise that Coral has died, and they recall that priest she protected.

Mr. Tench is working on the bad tooth of the Jefe, and he tells him that his wife has written to him and wants a divorce. Outside below in the courtyard Mr. Tench hears commotion and looks out the window to see a firing squad getting ready. A small man is led out and Mr. Tench recognizes him as the priest who had shared brandy with him. The priest is shot, and the body is dragged away. The event repulses Mr. Tench and brings over him a feeling of loneliness.

The woman with the children who had harbored the priest tells her children the story of Juan the martyr. The boy asks if the priest the police shot today was a martyr, and the mother assures him he was. When the boy goes to bed he has a dream about the priest and his funeral, but a knock on the door wakes him and upon answering it finds it is another priest coming to stay.

###

I’ve been trying to find a way to wrap up this novel, and I admit it’s been a little difficult. Some have said this is a very depressing novel. Perhaps that is unavoidable given its topic. What makes this a great novel, a great Christian novel, and great Catholic novel? I’ll try to highlight a few points, which I think will lift some of the gloom off the story.

First off this is a first rate novel because of its crisp narrative, its memorable characters, and its wonderfully suspenseful plotting. Graham Greene is a master storyteller. Coupling the central character (the whiskey priest) with a different character not only moves the plot along but creates a suspense for that anticipated conflict with his nemesis, the lieutenant, when the two will undoubtedly meet. As a story, the plotting is perfection: the whiskey priest, flawed and fallen, resisting the dystopian government that persecutes him. Can he escape? Does he want to escape? Will he survive? These are all questions that hang in the balance throughout the novel until its climatic end.

What elevates this novel even higher is the psychological portrayal of a very complicated central character. Above all this is a psychological novel which looks at the world through what I call Christian anthropology, that is, a Christian understanding of man. Within the whiskey priest are two human impulses that are rooted in a Biblical human nature: “What I do, I do not understand. For I do not do what I want, but I do what I hate.” (Rom 7:15) and “If God loved us, we must love one another” (1 Jn 4:7). And so the priest is caught in this existential conflict of doing what he cannot help from doing and doing it for love of his fellow man. Indeed, the whiskey priest can be seen as having the same “thorn in the flesh” that propels him forward to his fate as it did St. Paul, a grace of power from weakness made perfect (2 Cor. 7-10). The psychological novel came to its height in the first half of the twentieth century, and this novel is among the best and rooted in a Christian worldview. Even the minor characters have complex psychologies that can be traced to a Christian anthropology.

Third, this is also a great Catholic novel. Just about all the sacraments are interwoven through the novel but the governing action of most of the novel is the whiskey priest’s commitment to consecrate the Eucharist and spread it to the faithful. The whiskey priest is the only man left in this region of Mexico that can and is willing to be the instrument of grace that only a priest can be. Only a priest has the ability to transubstantiate bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ. And so then one understands why a good deal of the plot revolves around the priest’s search for available wine in a country where all alcoholic beverages have been made illicit. He risks being caught in order to provide the grace for the common folk to live in Christ: “He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him” (Jn 6:56). The whiskey priest is attempting to sanctify his time and place and the living souls around him through the consecration of the Eucharist, the Mass, the representation of the sacrifice of Christ, and in so doing bring life to the sterility of what has become a dystopian world.

You might consider the priest a failure, having the wine he had on hand thrown out by the mother of his child, and when he finally is able to buy more having it drunk from under him by the authorities. There are no baptisms in the entire novel, no confirmations, no marriages, no confessions. Indeed faced with his impending execution the priest cannot even get his own confession heard. There is no Sacrament of the Eucharist given out. In the one Mass he is able to celebrate the authorities storm the makeshift chapel right after the consecration, and so the whiskey priest has to hurriedly swallow the consecrated bread and wine before offering it to the congregation. No priest is given the Sacrament of Holy Orders. Indeed, one priest, Padre Jose, renounces his Holy Orders. And finally there are no last rites administered. The desperado gringo from the United States, shot and dying, refuses them. No sacrament in the novel is actually fulfilled in the dystopian region. The priest attempts to provide the graces of the sacraments in the context of a sterile wasteland. T.S. Eliot’s poem “The Waste Land” is certainly alluded.

But is the whiskey priest a failure? If the priest cannot give graces through the sacraments, he does provide graces through his very being. As I’ve pointed out the novel is structured where each chapter couples the whiskey priest exclusively with another character. While this is a really innovative way to move the plot forward it also allows us to see how the priest’s very being effects the other characters. And in each case the priest provides some sort of grace to the other character. As the priest interacts with the other, there is some sort of Cor Ad Cor Loquitur, heart speaking to heart. It’s as if the priest is a living sacrament, offering himself to each person and bringing God’s grace into their lives. One certainly can see the allusion in the narrative to Christ’s Passion and crucifixion, and certainly the whiskey priest can be seen as a Christ-figure in the novel, but I think it’s more than that. The priest’s execution is actually a re-presentation of Christ’s sacrifice, just like every Mass is a re-presentation of Christ. And so the priest is not a failure, just as Christ is not a failure. We see at the end a new priest come—a resurrection of sorts—and now the region has been sanctified by the whiskey priest’s death and the lives he has touched. Though the novel never reaches further into the future, we know how the dystopia turns out. Mexico renounces this anti-Catholicism and returns to faith.

This

short little novel is one of the giants of the twentieth century.

No comments:

Post a Comment