Completed

First Quarter:

“Leaf

by Niggle,” a short story by J.R.R. Tolkien.

“The

Turkey,” a short story by Flannery O’Connor.

“The

Trouble,” a short story by J. F. Powers.

Magnificat,

January 2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

“Theft,”

a short story by Katherine Ann Porter.

Book

of Baruch, a book of the Old Testament, RSV Translation.

Magnificat,

February 2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

Magnificat,

March 2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

Completed

Second Quarter:

Gospel

of John, a book of the New Testament, RSV Translation.

Introduction

to the Devout Life, a non-fiction work by St. Frances de

Sales.

“The

Blue Hotel,” a short story by Stephan Crane.

Magnificat,

April 2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

“A

Good Man is Hard to Find, a short story by Flannery O’Connor.

Oronooko

or The Royal Slave, a novel by Aphra Behn.

“The

Magic Paint,” a short story by Primo Levi.

Magnificat,

May 2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

Lord

of the World, a novel by Robert Hugh Benson.

The

Book Of Ezekiel, a book of the Old Testament, KJV

translation.

The

Book Of Ezekiel, a book of the Old Testament, RSV

translation.

Magnificat,

June 2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

Completed

Third Quarter:

“God

Rest You Merry Gentleman,” a short story by Ernest Hemingway.

Educated,

a non-fiction memoir by Tara Westover.

Magnificat,

July 2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

Brideshead

Revisted, a novel by Evelyn Waugh.

Utopia,

a novella by St. Thomas More.

Magnificat,

August 2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

Book

of Daniel, a book of the Old Testament, KJV Translation.

Last

Post,

the 4th novel of the Parade’s End Tetralogy by Ford Madox

Ford.

Book

of Daniel, a book of the Old Testament, RSV Translation.

Magnificat,

September 2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

Completed

Fourth Quarter:

Catherine

of Siena, a biography by Sigrid Undset.

“Hermann

the Irascible—A Story of the Great Weep,” a short story by Saki (H.H. Munro).

“The

Thistles in Sweden,” a short story by William Maxwell.

Magnificat,

October 2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

The

Book of Revelation, a book of the New Testament, KJV translation.

The

Book of Revelation, a book of the New Testament, RSV

translation.

Justification

by Faith and Works?: What the Catholic Church Really Teaches,

a booklet of theology by Jimmy Akin.

Quas

primas, an encyclical by Pope Pius XI.

“Blessed

Harry,” a short story by Edith Pearlman.

“Times

Square,” a short story by William Baer.

“The

Androgynous Papa Hemingway,” a review of Kenneth S. Lynn’s Hemingway by James Tuttleton.

Magnificat,

November 2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

I

Am Going: Reflections on the Last Words of Saints,

a non-fiction devotional work by Mary Kathleen Glavich, SND.

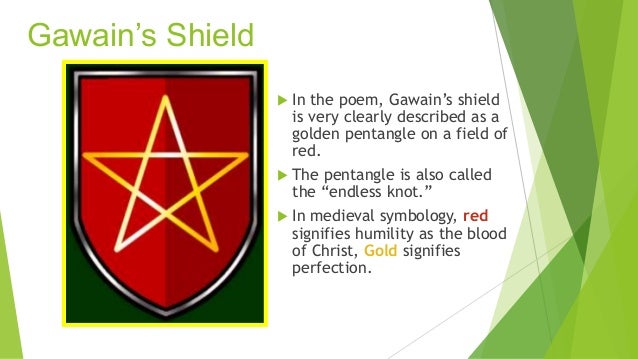

Sir

Gawain and the Green Knight, a long narrative poem by an anonymous

author, translated into contemporary English by Marie Borroff.

Sir

Gawain and the Green Knight, a long narrative poem by an anonymous

author, translated into contemporary English by Simon Armitage.

The

City of God Books 1-10, by Augustine of Hippo, translated

by William Babcock.

Magnificat,

December 2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

“Dédé,”

a short story by Mavis Gallant.

Currently Reading:

Dominican

Life: A Commentary on the Rule of St. Augustine,

a non-fiction work by Walter Wagner, O.P.

Catholicism:

A Journey to the Heart of the Faith, a non-fiction work by

Robert Barron.

Prince

Caspian, a novel from the Chronicles of Narnia series by C.

S. Lewis.

###

I

think this was a good year of reading.

Perhaps a little short of the amount from last year, but last year was

exceptional. This year I think I can say

was still at or above average. One thing

you will find added to my listing this year are the listing of Magnificat, a monthly devotional that

provides the daily Mass readings, lives of saints, and devotional

articles. I read most of it every

month. I have been doing so for years,

so this is not additional reading material.

I just never thought about listing it here. A typical edition runs about 450 pages every

month, and I read at least half of it.

That’s quite a bit of reading I never documented. You can assume that most of the years I have

been keeping this blog I have also been reading the monthly Magnificat.

On

a comprehensive level, I read twelve books and twenty-four “shorts,” a short

being lesser than a book length work.

That’s one book per month and two shorts per month, which is spot on my

intended annual goal, I should also

state that three books are still being read and are more than half way

through. When I finish, they’ll wind up

being counted into next year’s reading but if you consider them here they

pushed my overall reading above my goals.

Of

the books completed, five were non-fiction and seven were fiction. Let’s start with the non-fiction. Of those, one was a work of theology (Part 1

of St. Augustine’s City of God), one

a biography (Sigrid Undset’s Catherine of

Siena), one a memoir (Tara Westover’s Educated),

and two devotional books (St. Francis de Sales’ Introduction to the Devout Life and Kathleen Glavich’s I Am Going: Reflections on the Last Words of

Saints).

My

edition of City of God, translated by

William Babcock, is physically two books, which I call the first, Part 1 (Books

1-10). The entire City of God is over a thousand pages, so you can see why I count it

as two separate books. And to complicate

matters, what we might call chapters within the work, St. Augustine calls

“Books.” Part 1 deals with the history

of Rome, her pagan religion, and Greco-Roman philosophy as it relates to

Christianity. It can be a bit dry

reading, but if you have an interest in classical Rome it can be quite

fascinating. It’s a great classic of

philosophy and theology and a core part of the Western intellectual

tradition. Part 2 deals with Judaism and

Christianity itself, so I can’t wait.

Sigrid

Undset’s Catherine of Siena should be

familiar to readers here. It’s my second

read of this superb biography. I don’t

think I have actually blog posted on the same book on separate occasions. This is the first time. As you know if you go back to my 2013 posts,

this was a transformational book for me. Not only did it make me more devout

but it led to my devotion to St. Catherine as my patron saint. I think I have called her the patron saint of

this blog. The book is just as superb on

a second read.

If

you read reviews of Educated, Tara

Westover’s memoir of her upbringing to get an education when her father refused

to send her to school (she ultimately went to college and then earned a Ph.D. from

Cambridge in United Kingdom), you will see reviews at the two extremes: either

you loved it or did not think it great.

I ended up with those that didn’t find it well put together, but it does

hold your interest. She’s a smart young

lady but if you check my review here on my blog you’ll see I think she left too

many answered questions.

The

two devotional books were both great reading.

St. Francis de Sales’ Introduction

to the Devout Life is the absolute best work on spiritual direction. Actually I would consider this a manual for

spiritual direction. In my posts I said

I was sorry I had bought this as an eBook.

A physical book should be kept on one’s bedside for frequent

review. Kathrine Glavich’s devotional I Am Going uses famous saint’s dying

last words as a starting point for a devotional reflection. There are about one hundred saints whose last

words are identified and, with the background and reflection, amount to a

couple of pages for each saint. That

provides a nice bedtime reading where if you read one saint per night, you can

finish in just over three months.

It

is interesting that the fictional works divide between those written in the 20th

century and those written in pre-modern times.

Though I claim seven fictional works, there are six actual works since I

count Sir Gawain and the Green Knight twice

because I read two different translations.

Sir Gawin is also not an

actual novel but a long narrative poem that reads like a novel. The three pre-modern works were Sir Gawain (written around 1370), St Sir

Thomas More’s Utopia (1516), and

Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko: or, the Royal

Slave (1688). Sir Gawain in any translation is a joy to read, while Utopia and Oroonoko are a bit more problematic. Once I understood them I appreciated them

more. Read my blog entries. You can search them in the search box at the

top left of the blog page.

The

more contemporary works were Robert Hugh Benson’s dystopian novel, Lord of the World (1907), Evelyn Waugh’s

Brideshead Revisted (1945), and Ford

Madox Ford’s Last Post (1928), the

fourth and last novel in Ford’s Parade’s

End tetralogy. Brideshead is a great classic of the 20th century, and

deservedly so, and Lord of the World

is an underrated novel which should be considered a classic. Last

Post brought to a close my reading of Parade’s

End, and while I think Parade’s End as

a whole as a classic of the 20th century, none of the four novels on

their own holds up as a great work. The

tetralogy is really one novel divided into four books. You need to read all four to appreciate the

work.

Biblical

reads were Books of Baruch, Ezekiel, and Daniel for the Old Testament, and

Gospel of John and the Book of Revelation for the New Testament. Ezekiel, Daniel, and Revelation were read

twice for the King James and RSV translations.

(Note: I have mentioned my desire to have a complete read through in the

KJV for English language appreciation purposes; that’s why I read two

translations.) Baruch is only in

Catholic Bibles, so no KJV. I had

already read the Gospel of John before in the KJV; no point in reading it again. The reading of Revelation in KJV completes

the New Testament in KJV. I am now just

left with the prophets after Daniel and I will have accomplished my KJV goal.

Last

year I started assessing the short stories in their own blog post, and I will

do that again this year. But I should

note the non-fiction shorts I read this year.

There were three: Pope Pius XI’s 1925 encyclical, Quas primas, establishing the Feast of Christ the King, an essay by

James Tuttleton titled, “The Androgynous Papa Hemingway,” on the hidden

sexuality of Ernest Hemingway, and a booklet by the Catholic Apologist, Jimmy

Akin titled, Justification by Faith and

Works?: What the Catholic Church Really Teaches, on the Catholic understanding

of the difficult theological term “justification.” All three were worthwhile reads.

Finally

I should mention the three books I’ve not finished. Bishop Robert Barron’s Catholicism is one of the best contemporary books on understanding

the faith. I’m about 70% completed

according to my Kindle. C.S. Lewis’s Prince Caspian is the fourth book of the

Chronicles of Narnia series. I had pledged to read one book of the series

per year with my son. You have to pull

teeth to get my son to read. We’re 78%

done. Dominican Life by Fr. Walter Wagner, O.P. is a book reflecting on

life in the Order of Preachers using the elements of their Rule as a taking off

point for discourse. I’m 62% into the

book.

Here

is the same reads listed above chronologically now listed by type of work. Some may find this is easier to read.

Full Length Books: 12

Non-Fiction:

5

Introduction

to the Devout Life, a non-fiction work by St. Frances de

Sales.

Educated,

a non-fiction memoir by Tara Westover.

Catherine

of Siena, a biography by Sigrid Undset.

I

Am Going: Reflections on the Last Words of Saints,

a non-fiction devotional work by Mary Kathleen Glavich, SND.

The

City of God Books 1-10, by Augustine of Hippo, translated

by William Babcock.

Fiction:

7

Oronooko

or The Royal Slave, a novel by Aphra Behn.

Lord

of the World, a novel by Robert Hugh Benson.

Brideshead

Revisted, a novel by Evelyn Waugh.

Utopia,

a novella by St. Thomas More.

Last

Post,

the 4th novel of the Parade’s End Tetralogy by Ford Madox

Ford.

Sir

Gawain and the Green Knight, a long narrative poem by an anonymous

author, translated into contemporary English by Marie Borroff.

Sir

Gawain and the Green Knight, a long narrative poem by an anonymous

author, translated into contemporary English by Simon Armitage.

Bible: 8

Old Testament: 5

Book

of Baruch, a book of the Old Testament, RSV Translation.

The

Book Of Ezekiel, a book of the Old Testament, KJV

translation.

The

Book Of Ezekiel, a book of the Old Testament, RSV

translation.

Book

of Daniel, a book of the Old Testament, KJV Translation.

Book

of Daniel, a book of the Old Testament, RSV Translation.

New Testament:

3

Gospel

of John, a book of the New Testament, RSV Translation.

The

Book of Revelation, a book of the New Testament, KJV translation.

The

Book of Revelation, a book of the New Testament, RSV

translation.

Magazines:

12

Magnificat,

January 2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

Magnificat,

February 2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

Magnificat,

March 2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

Magnificat,

April

2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

Magnificat,

May

2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

Magnificat,

June

2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

Magnificat,

July

2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

Magnificat,

August

2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

Magnificat,

September

2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

Magnificat,

October

2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

Magnificat,

November

2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

Magnificat,

December 2020, a monthly Catholic devotional.

Short Works:

23

Non-Fiction: 3

Justification

by Faith and Works?: What the Catholic Church Really Teaches,

a booklet of theology by Jimmy Akin.

Quas

primas, an encyclical by Pope Pius XI.

“The

Androgynous Papa Hemingway,” a review of Kenneth S. Lynn’s Hemingway by James Tuttleton.

Short

Stories: 13

“Leaf

by Niggle,” a short story by J.R.R. Tolkien.

“The

Turkey,” a short story by Flannery O’Connor.

“The

Trouble,” a short story by J. F. Powers.

“Theft,”

a short story by Katherine Ann Porter.

“The

Blue Hotel,” a short story by Stephan Crane.

“A

Good Man is Hard to Find, a short story by Flannery O’Connor.

“The

Magic Paint,” a short story by Primo Levi.

“God

Rest You Merry Gentleman,” a short story by Ernest Hemingway.

“Hermann

the Irascible—A Story of the Great Weep,” a short story by Saki (H.H. Munro).

“The

Thistles in Sweden,” a short story by William Maxwell.

“Blessed

Harry,” a short story by Edith Pearlman.

“Times

Square,” a short story by William Baer.

“Dédé,”

a short story by Mavis Gallant.

###

I

have written blog posts on most of these works.

I may never have pointed this out before, but up on the top left corner

of the blog is a search feature. Type

the name of the work or the author and the various blog posts will come

up.

###

I've

posted on the details on the short story read: Part 1 here and Part 2 here.