This quote will require some context. It comes from a poem by Thomas Merton, the Trappist monk, mystic, writer, and poet. His prose writing is quite good, known for his spiritual biography, The Seven Story Mountain, but also known for his books on the contemplative life, social issues, literary works, and whole host of other topics. His poetry in my opinion is hit and miss, but his hits can be exceptional. I think this poem is exceptional.

The first thing to keep in mind is that the poem was written subsequent to Ernest Hemingway’s suicide by self-inflicted shotgun shot. The second thing to remember is that Merton was influenced by Hemingway as a young man. Merton was born in 1915, and had wanted to be a writer from a very young man. Hemingway was perhaps the central writer of the post WWI era, commonly called “the lost generation” which documented the trauma of the war. Merton as a young man felt the post war angst and ultimately led him to reject his atheism, convert to Catholicism, and become a Trappist monk at the monastery, Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani in Kentucky. His life perhaps flows in the opposite direction from Hemingway’s life. The third thing to remember is that Merton, now twenty years a monk, and also a writer, can identify as Hemingway’s doppelgänger, his literary twin but with a very different side.

An Elegy For Ernest

Hemingway

By

Thomas Merton

.

Now for the first time on the night of your death

your name is mentioned in convents, ne

cadas in

obscurum.

Now with a true bell your story becomes final. Now

men in monasteries, men of requiems, familiar with

the dead, include you in their offices.

You stand anonymous among thousands, waiting in

the dark at great stations on the edge of countries

known to prayer alone, where fires are not merciless,

we hope, and not without end.

You pass briefly through our midst. Your books and

writing have not been consulted. Our prayers are

pro defuncto N.

Yet some look up, as though among a crowd of prisoners

or displaced persons, they recognized a friend

once known in a far country. For these the sun also

rose after a forgotten war upon an idiom you made

great. They have not forgotten you. In their silence

you are still famous, no ritual shade.

How slowly this bell tolls in a monastery tower for a

whole age, and for the quick death of an unready

dynasty, and for that brave illusion: the adventurous

self!

For with one shot the whole hunt is ended!

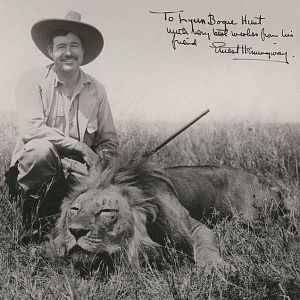

The poem is not written in meter but in straight prose, which I think is a nice tip of the cap to Hemingway’s great prose, which at its best could be poetic. There are several references to monastery life that one should know to fully understand the poem. In the first stanza, he mentions that now that Hemingway has died, the convents will be adding his name to the prayers for the dead, ne cadas in obscurum, “unless they fall into the darkness.” It is a line from a Mass for the dead, and the line can be translated as “Deliver them from the lion's mouth, lest hell swallow them up, lest they fall into darkness.” It is noteworthy that Hemingway had hunted lions and featured them in a couple of his short stories.

The second stanza is an elaboration of the first. Now that Hemingway’s story has become final, he will be included in the monk’s daily “offices,” which refer to the Liturgy of the Hours which monastics pray seven times a day.

The third stanza I believe is an allusion to Dante’s Divine Comedy, where Hemingway’s soul stands among thousands of those entering the afterlife, especially referring to Purgatory here since he hopes the fires will end. The fourth stanza refers to prayers prayed for the deceased, “pro defuncto,” N referring to a name to be added, Nominatim. The interspersing of Latin and the slow prosaic lines gives the poem a praying quality, as if it were Gregorian chant. I can see this poem being chanted.

The fifth stanza is Merton’s homage to Hemingway. In the crowd of souls he is recognized, and a reference is made to Hemingway’s post WWI novel, The Sun Also Rises, and to Hemingway’s great prose that captured the trauma of the war.

If the fifth stanza is a homage, the sixth stanza captures the tragedy of Hemingway’s life. It also alludes to another of Hemingway’s novels, For Whom the Bell Tolls, and to the unquenchable desire for adventure that consumed Hemingway’s life. It alludes to a morbid fascination that Hemingway had with death, both with killing animals in hunts or in bull fights and with killing people in wars, and with his own death which in his adventures could be seen as a death wish. Merton refers to these adventures as “brave illusions, which seen from Merton’s religious point of view was a sign of a hurt inside of Hemingway’s heart which was never healed from the trauma of the First World War. Merton healed his hurt through his Catholic faith.

Which brings us to the final one line seventh stanza, which ends the poem like the gunshot it alludes to. “For with one shot the whole hunt is ended!” The hunter hunts himself! Ernest Hemingway killed himself on July 2nd, 1961 bringing his adventures, his writing, and his life to an end.

###

Postscript:

As

I’ve thought about this more, the parallels between Hemingway and Merton are

even stronger. It’s not that widely

known but Hemingway converted to Catholicism, and though he considered himself

a bad Catholic, he he never left it. He

was instrumental it seems in leading Gary Cooper, one of his best friends, into

also converting. A very good article on

Hemingway’s Catholicism is “The troubled Catholicism of Ernest Hemingway,” by

Robert Inchausti. From the article:

Hemingway was raised in a

Congregationalist Protestant home, and his first conversion to Catholicism

occurred when he was a 19-year-old and volunteer ambulance driver in Italy

during World War I. Two weeks into the job, he was delivering candy to soldiers

on the frontlines when he was hit by machine-gun fire and more than 200 metal

fragments from an exploding mortar round. An Italian priest recovered his body,

baptized him right on the battlefield and gave him the last rites.

Hemingway later described

what happened this way:

“A big Austrian trench

mortar bomb of the type that used to be called ash cans, exploded in the

darkness. I died then. I felt my soul or something come right out of my body,

like you’d pull a silk handkerchief out of a pocket by one corner. It flew around and then came back and went in

again and I wasn’t dead anymore.”

After having been

anointed, Hemingway described himself as having become a “Super-Catholic.” It

was a near-death experience that changed the course of his life. After the war,

he went to work as a foreign correspondent in Paris. And eight years later —

after his first marriage failed — he undertook a second, more formal conversion

process in preparation for marriage to his second wife, devout Catholic Pauline

Pfieffer.

It was at this time that

Hemingway changed the title of his unpublished first novel, tentatively titled

“Lost Generation,” to “The Sun Also Rises.” And writing to another friend, he

declared, “If I am anything I am a Catholic . . . I cannot imagine taking any

other religion seriously.”

He attended Mass (albeit irregularly) for the rest of his life and went on pilgrimages, received confession, had Masses said for friends and relatives, and raised his three sons as Catholics. Most of his novels are set in Catholic countries, and his last great hero (Santiago of “The Old Man and the Sea”) was a devout suffering servant, much in the cruciform mold of most of his heroes. When he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954, he gave away the medal as a votive offering to “Our Lady of Cobre” in Havana.

But

Hemingway considered himself a bad Catholic, one who could not live up to the discipline

of the Christian life. Again from the Inchausti

article:

In a letter to his friend

Father Vincent Donavan in 1927 just before he married his second wife,

Hemingway wrote, “I have always had more faith than intelligence or knowledge

and I have never wanted to be known as a Catholic writer because I know the

importance of setting an example — and I have never set a good example.”

Unlike James Joyce, Hemingway didn’t renounce his faith; and unlike Flannery O’Connor, he never promoted it. He thought of himself, like many of his protagonists (Nick Adams, Jake Barns, Robert Jordan, Francis McComber and Santiago), as a man struggling to live with grace and die a good death in a violent, unforgiving world where all of us must suffer.

Though not a formal Catholic ceremony, the graveside services were conducted by Rev. Robert J. Waldmann, pastor of St. Charles Roman Catholic Church in Hailey and of Our Lady of the Snows in Ketchum as stated in this contemporaneous NY Times article.

So the parallels and differences are stark. Hemingway converted to Catholicism but led a seeker’s life of “brave illusions.” Merton converted to Catholicism but settled into a monastic life, which is a life of total stability, the very opposite of the restless heart.

“Our

hearts are restless, O Lord, until they rest in you.” -St. Augustine of Hippo.

No comments:

Post a Comment