A friend of mine sent me an email the other day with an urging to check out a particular poem. Here is her note:

When you have time,

Manny, please look at this poem:

“Goshawk” By poet Peter Kane Dufault

I happened upon it and was struck by its excellence yet violence. If you read it, tell me if it reminds you of a dark, shadowy likeness of Hopkins’ “The Windhover.’’ It really seems that way to me, a world without God.

I love it when friends ask me questions on literature. It pricks something in me to investigate.

First,

you can find the poem at Poetry Nook,

but here’s the poem.

Goshawk

by Peter Kane Dufault

That harbinger of God's

hardness, North

American Goshawk — storm-

grey above, ice-grey

beneath — segment

of a winter azimuth — de-

tached herself from this

morning and

seized a black hen and

caromed

thirty yards through the

soft snow, wrenching

feathers and flesh out,

too

blood-crazy to kill

clean. . . .

Tell me

if it's not hard how a

haggard

hasn't even the hangman's

mercy

but tears the heart out

alive — that she

should have been made so;

and so, too, that when

the dog

ran yapping and drove her

off,

the grey crucifer

levitated

in such a cold pride of

windblown

lightness over the tines

of the trees

you'd have forgiven her,

even

if she could have torn

in that worse way there

is:

with a word, never breaking the skin.

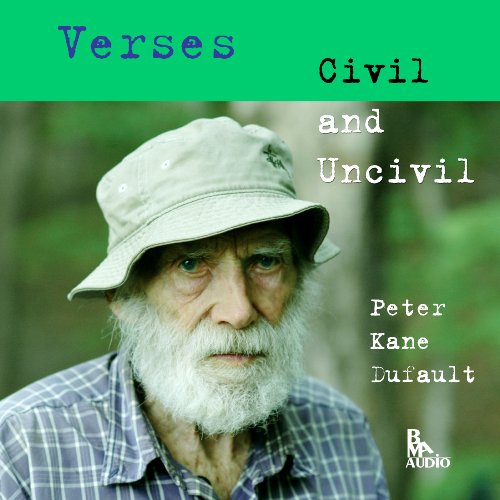

I had never heard of Peter Kane Dufault before. He’s got a Wikpedia entry and a listing in Poetry Foundation, so he’s a poet of some merit. He lived through most of the 20th century (1923-2013), fought in WWII, and even ran for Congress on an Anti-Vietnam War platform. The Poetry Foundation bio note says he was highly thought of by some more well-known poets: “Poets such as Marianne Moore and Ted Hughes championed Dufault, as did New Yorker editor Howard Moss, who published the poet 44 times.” Poetry Foundation lists six poems attributed to him, but none are as good as “Goshawk.” Searching the internet you can find some two dozen poems of his. Again, nothing I found as good as “Goshawk,” but of note you might want to read “After Boxing” and “Paramath.”

Perhaps

the best of the obituaries is by Brad Leithauser in the New Yorker, published on June 7, 2013, several weeks after Dufault’s

passing. Here’s his opening:

A marvellous poet whom you’ve probably never heard of died some weeks ago. His name was Peter Kane Dufault, and at the time of his death he was a couple of days short of ninety. On the face of it, his lack of renown is surprising, for he had some prominent supporters, including Marianne Moore and Richard Wilbur and Ted Hughes and Amy Clampitt. He was also embraced by Howard Moss, the poetry editor of The New Yorker from 1948 until 1987. Dufault published forty-four poems in the magazine, nearly all of them during Moss’s tenure.

Leithauser characterizes Dufault as that poet we’d all wished we had known, a “pure poet” who lived his life in obscurity and simplicity.

It’s tempting to overstate the virtues of the recently dead, so I’ll resist declaring that, at the time of his death, Dufault was my favorite living American poet. But he was certainly among the five or six whose work counted most for me. In one way, he was preëminent: I came to think of him as the Pure Poet. If this was a romantic image, it was a romanticism he encouraged.

Perhaps

if one had to reach for what Dufault’s themes centered around, I think this

little characterization captures it.

He was constantly posing new theological questions, in an era often hostile to poetry of devotion. He looked hard at the natural world, then looked hard at its spiritual implications.

Here

Leithauser captures Dufault’s style.

I first came upon him in the seventies, in “The New Yorker Book of Poems.” I fell hard for “In an Old Orchard,” with its abandoned farm “still pitifully gathering all / windfalls onto its damp lap of graves,” and looked up his two out-of-print collections, “Angel of Accidence” (1954) and “For Some Stringed Instrument” (1957). I didn’t know then that Marianne Moore had been a fan, but affinities between them were easy to spot: Dufault, too, had an eerily sharp eye for the more idiosyncratic dwellers of the animal kingdom. Manx cats and tarsiers and mud-dauber wasps and mastodons inhabited his stanzas. He was like her, too, in being quite fanciful in his imagery (an old turkey with a head “like a loading-hook from a drowned galleon,” a hefty starling seen as a “sampler-shape whose bid / to be a bird / suffers from thickness of the thread”) while always respecting his creatures’ fierce and inalienable reality: you never had the feeling that his was a denatured zoo, a menagerie of mere symbols. A reader was in danger of getting stung if he mistook one of Dufault’s wasps for an emblem.

It

sounds like Dufault’s work is similar to Marranne Moore’s, who had a sharp eye

for observation, a precise word or metaphor to capture it, and loved to write

about animals for their wondrous nature.

Leithauser continues.

In 1993, a book of selected poems, “New Things Come Into the World,” appeared, published by a small press, Lindisfarne, which normally didn’t publish poetry. At that time, I’d never met Dufault, though we’d exchanged some letters. I reviewed “New Things Come Into the World” in the New York Review of Books, writing with that special charged eagerness that comes of introducing a little-known treasure to a potentially wide audience. I called him a “poet of vivid landscapes.” I called him “as fine an ‘animal poet’ as any American now going.” I compared him to Moore and Elizabeth Bishop and Clampitt and May Swenson.

Finally

Leithauser felt a certain pride in knowing a poet of distinction that lived in

obscurity.

Though he slowed down, creatively, in his last decade, he continued to write beautiful poems, and did so, nobly, in an undeserved obscurity. Now and then I’d come upon someone, in person or in print, who shared my enthusiasm, and I’d feel that clandestine bond which comes with membership in a small high-minded club. I felt this keenly when I read Ted Hughes’s blurb for a later Dufault collection, “Looking in All Directions” (2000): “So fresh and new and itself… wonderful stuff. Snatches those uncatchable moments—like snatching a butterfly out of the air—then letting it go undamaged. So nimble and delicate.”

###

Now to the poem. It’s an interesting poem. It's not Gerard Manly Hopkins. It's very visual, so it captures the reader. Are there similarities to Hopkins? This is a very different poem that “The Windhover.” (I provided a detailedanalysis of Gerard Manly Hopkins’, “The Windhover.”) It is quite possible Dufault is alluding to “The Windhover” but I just don’t see the interdependence. Perhaps Dufault’s image of the goshawk “detaching herself from the “winter azimuth” is an allusion to the Hopkin’s image of a “dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon,” Or it’s coincidental imagery or Dufault just liked the image so much he reinvented it for his purpose. An allusion is more than just reference; it requires significance, and I’m not getting the significance.

Other than Dufault's use of alliteration I do not see other similarities. Dufault does not use any real rhythm, sprung or conventional. He's very prosaic, modernist, free verse, though his diction is terse, which gives it power, especially for a violent poem. I'm baffled by Dufault's use of breaking words and phrases at the end of a line. Hopkins does it to keep meter. Not sure why Dufault does it. Perhaps as an aesthetic capturing of the theme of ripping things apart? That would be skillful on his part.

Dufault's theme has been done many times: one finds in nature a certain viciousness, (he calls it a "hardness") and one points to God for it, either to condemn God, to "prove" God doesn't exist, or to point to some great spiritual meaning in the act of animals killing animals.

Can you tell which of the three Dufault is expressing? I think it's the latter but I'm not sure, and if it is the latter then what is this great spiritual meaning in the act of a hawk killing a chicken? I've pondered it for a while. He sees in the hawk gliding above a cross (“the grey crucifer levitated”), which is a nice metaphor, but what does it suggest? Isn't Christ the one who gets killed and not the killer?

Why is the hawk the "harbinger" of God's hardness? Is this an allegory? A harbinger is one who comes ahead of another. So is God going to come and destroy us? Perhaps. Or is the allegory a representation of the Calvinist interpretation of the crucifixion, where God's wrath is redirected on the Son and thereby satisfied? I don't know. And is that a reference to God at the end, imagining the hawk killing with a word instead of with violence (“if she could have torn/in that worse way there is:/with a word”)? God creates with a word; Christ is the Word made flesh. And why is killing through a word "the worse way"? You got me.

This

may all hold together and be a great poem, but given that I have all these

questions and still can't get beyond the surface events I wouldn't call this a

great poem. I do love how it reads. Alliteration can be showy and stilted, but when

done well as here it really drives the point as in the second stanza:

Tell me

if it's not hard how a

haggard

hasn't even the hangman's

mercy

but tears the heart out

alive — that she

should have been made so

…de-

tached herself from this

morning and

seized a black hen and

caromed

thirty yards through the

soft snow, wrenching

feathers and flesh out,

too

blood-crazy to kill clean. . . .

The alliteration of “feathers and flesh” along with the hard C’s of “caromed,” “crazy,” “kill,” and “clean” adds to the very visual moment of struggle and brutality. I am glad to have been introduce to Peter Kane Dufault. I will have to remember him if I run across his work again.

In my search I found a couple of videos of Mr. Dufault.

First

an extemporaneously composed poem criticizing America:

Second,

here is a trailer to a documentary movie of his views” What

I Meant to Tell You: An American Poet's State of the Union.”

He

was definitely anti American, or of a different America to give him his due. In his obituary Leithauser did say he would

have edited out Dufault’s political poems.

They are not that good. We would

have disagreed vehemently, but still in my engagement on his life and this poem

I grew to like Peter Kane Dufault. Yes I

can see how he was a “pure poet.”

Postscript:

I received a reply from my friend who had originally sent me the email on the poem.

Her

Comment:

I looked Peter Kane Dufault’s work up a little more and found that he wrote a poem called ‘’Peregrines,’’ and in that poem he quotes directly from ‘’The Windhover.’’ He had a rich imagination and an exceptional way with words but ‘’Peregrines‘ is not his best work. Unfortunately, this reader found it empty and meaningless. You mentioned that he was anti-American. Do you mean ‘’progressive left,’’ ‘’woke’’ anti-American?

My

reply:

I really enjoyed "Peregrines"! It's a poetic ramble, a jazzy improvisational piece that streams language around an emotion and theme. It reminds me of the Beat poets, Lawrence Ferlinghetti in particular. I have a secret crush for that poetry. It's lesser poetry than more structured and sculpted but I find it fun. My trash food addiction! ;)

Dufault is an old time

Liberal, someone of the Beat Generation.

I think that's a good analogy. He’s

definitely progressive and definitely "woke" but aren't they

all? In music he would be like the folk

music types. In fact he reminds me of

Pete Seeger. And amazingly they lived

almost the exact same years (1919-2014).

No comments:

Post a Comment