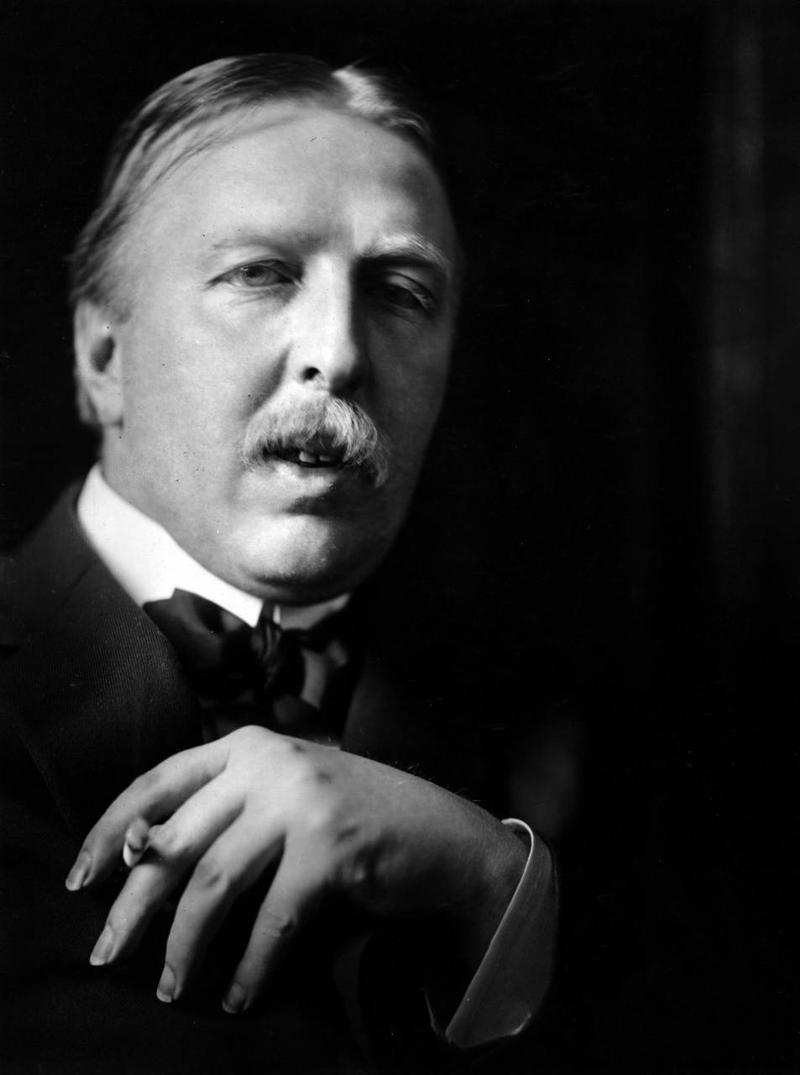

This is my review of Ford Madox Ford’s Parade’s End that I posted on Goodreads.

I gave it four stars. It took me about six years. I finally reached the end! Was it a labor of love? Not exactly, but it wasn’t a slog either. Parade’s end is a tetralogy, a sequence of four novels. I read one novel each year while skipping a couple of years in between. I did it because my edition of four novels adds up to 906 pages, and I hate to commit to one work for an extended period of time. I don’t recommend that for this work. I think it would be best to read them together. I personally would not consider each of the four novels a standalone. It would be incomplete. A sense of finality is finally arrived at the end of the fourth novel.

Is this a great work? Yes, it’s high modernism, and with that be warned. It can be difficult. Much of the major action is not narrated, except perhaps for one major war scene. Much of the narrative is filtered through the consciousness of the central characters. And yet it is a historical novel, traversing from before the First World War, through the war, and then in the aftermath of the war. At the core of the novel are the psychological shifts of the many characters over the course of that historical span. Through the minds of the characters—and the novel is told in a third person limited narration, shifting in and out of stream of consciousness—one reads the story of a great shift in British history, the transition of prideful, global empire to an exhausted and humbled nation. It is through the summation of individual consciousnesses that one intimates at a psychological history of a time and place.

The central characters of the novel are Christopher Tietjens, aristocrat, soldier, patriot, even saint, and his wife, Sylvia, one of the most distinct characters in all of literature: unfaithful, cruel, stunningly beautiful, aristocratic, and utterly self-confident. If Christopher is near a saint, Sylvia is narcissistic and self-indulgent. Here is one of the early descriptions of Sylvia, from the first of the novels, Some do not…

Sylvia Tietjens rose from her end of the lunch-table and swayed along it, carrying her plate. She still wore her hair in bandeaux and her skirts as long as she possibly could; she didn’t, she said, with her height, intend to be taken for a girl guide. She hadn’t, in complexion, in figure or in the languor of her gestures, aged by a minute. You couldn’t discover in the skin of her face any deadness; in her eyes the shade more of fatigue than she intended to express, but she had purposely increased her air of scornful insolence. That was because she felt that her hold on men increased to the measure of her coldness. Someone, she knew, had once said of a dangerous woman, that when she entered the room every woman kept her husband on the leash. It was Sylvia’s pleasure to think that, before she went out of the room, all the women in it realised with mortification—that they needn’t! For if coolly and distinctly she had said on entering: ‘Nothing doing!’ as barmaids will to the enterprising, she couldn’t more plainly conveyed to the other women that she had no use for their treasured rubbish.

Ha! She couldn’t care less about the “treasured

rubbish” of other women’s husbands. As

you can see the prose is superb. Ford

Madox Ford has to be one of the finest prose stylists of the 20th

century, and this novel (or set of novels, however you wish to think of them)

is his finest achievement. Here is a

passage from the third novel, Parade’s

End, where Christopher, in the middle of battle, saves a young soldier who

is no more than a boy.

Fury entered his

mind. He had been sniped at. Before he had had that pain he had heard, he

realized, an intimate drone under the hellish tumult. There was reason for furious haste. Or, no….They were low. In a wide hole. There was no reason for furious haste. Especially on your hands and knees.

His hands were under the slime, and his forearms. He battled his hands down greasy cloth; under greasy cloth. Slimy, not greasy! He pushed outwards. The boy’s hands and arms appeared. It was going to be easier. His face was not quite close to the boy’s, but it was impossible to hear what he said. Possibly he was unconscious. Tietjens said: ‘Thank God for my enormous physical strength!’ It was the first time that he had ever had to be thankful for great physical strength. He lifted the boy’s arms over his own shoulders so that his hands might clasp themselves behind his neck. They were slimy and disagreeable. He was short in the wind. He heaved back. The boy came up a little. He was certainly fainting. He gave no assistance. The slime was filthy. It was a condemnation of a civilization that he, Teitjens, possessed of enormous strength, should never have needed to use it before. He looked like a collection of mealsacks; but at least he could tear a pack of cards in half. If only his lungs weren’t…

So why only four stars? If it wasn’t a slog? Yes, but I have to say it was difficult to engage. With the action off stage, with the characters vaguely interacting with each other, with the subtly of psychological shifts, which you are never sure if you are comprehending correctly, a reader is left in a sort of limbo state, unsure what the author really intends. I made it worse by reading it over so long a time. Reading Parade’s End is like looking at a complex painting, where the important subject is not in the foreground but in the distant background, where you can’t quite bring it into focus. In the end one is left with an impression, rather than an idea, of a time and place and people. Perhaps this is the modernist aesthetic that Ford intended. If he did, then he crafted a masterpiece.

I want to leave with a brilliant quote from the second novel, No More Parades, that I think sums up the novel and the war and the story.

No more Hope, no more

Glory, no more parades for you and me any more. Nor for the country... nor for

the world, I dare say... None... Gone.

Perhaps someday I will re-read it and give it five stars.

No comments:

Post a Comment