Here

are some random thoughts and observations on the Jupiter cantos.

Going

back to Canto XVIII, the way the lights scroll across the sky, forming letters

which spell words, suddenly coalesce, and then forming shapes is, if you think

on it, an incredible feat of imagination for someone in Dante’s time. This is like a video game playing itself out

on a “screen” in front of Dante. We can

easily conceptualize it today, but how could someone in the Middle Ages

conceptualize such visuals is stunning.

And then Dante (the author) takes it a step further in the visual

“technology.” A full bodied bird image

forms then morphs into a fleur de lily, and then morphs again into the head of

the eagle. Dante is actually visualizing

the morphing of shapes. Amazing!

The

eagle, if you missed it, is symbolic for the Roman Empire, and represents human

justice. When the eagle speaks, it is each

individual light speaking in unison, and this has particular significance when

considering the notion of justice. What

is justice but the application of a society’s values, and each individual

member of that society contributes his input to establishing justice. Think of it as a jury of twelve coming to a

single verdict. The verdict is the

single, unified voice of the jury group, each member having contributed to that

voice.

Notice

the wonderful imagery Dante (the author) uses to describe that amalgamation of

voices into one.

Just as from many coals

we feel a single heat,

so from that image there

came forth

the undivided sound of

many loves. (XIX.19-21)

Each

single coal individually provides heat, but the amalgamation of each coal’s

contribution is felt as a single heat source.

And then in the following tercet, Dante addresses the eagle as an

amalgamation of a variety of scents:

And I then answered: 'O

everlasting blossoms

of eternal bliss, you

make all odors

blend into what seems a

single fragrance…(22-24)

In

some of the other instances when a holy soul or Beatrice reads Dante’s mind

about a question, they articulate the question and then answer it. In this section, when Dante (the character)

has his mind read on the doubt that has formulated, unlike the previous

instances the eagle starts answering the question before it is

articulated. I think this might confuse

some readers. In Canto XIX, from lines

22 through 33, Dante (the character) tells the eagle he has something on his

mind. From lines 40 through 69 the eagle

starts answering the question which has not been articulated. In essence what the eagle is saying is that

Dante cannot see, does not have the vision to see, the entire creation. Finally from lines 70 to 78 the eagle

articulates the hypothetical about a man born in India who can never know the

faith. Where is the justice in not

having the means to salvation?

It

is fitting that in the sphere of Jupiter, that of just rulers, the eagle turns

judgement back at Dante (the character).

When Dante questions the justice of a pagan incapable of achieving

salvation, the eagle says:

'Now, who are you to sit upon the

bench,

judging from a thousand miles away

with eyesight that is shorter than a span?

(XIX.79-81)

To

paraphrase, “Who are you with your limited eyesight to judge God?” It’s not just questioning God; it’s judging

God.

Dante

(the author) seems to associate proper justice with eyesight. Here he contextualizes Dante (the

character)’s incorrect judgement of God with limited sight, but when in Canto

XX the eagle catalogues six great rulers who were just, their points of light

were the ones that made up the eagle’s eye.

Indeed, the eagle was known in the middle ages as the creature with the

sharpest eyesight.

How

ingenious of Dante to formulate an acrostic (a series of lines or verses in

which the first, last, or other particular letters when taken in order spell

out a word, phrase, etc.) when cataloguing the bad twelve kings that are living

in Dante’s time. The acrostic spells lue, which means plague. These kings are a plague.

Again

Dante (the author) shows his contempt for his contemporary world by locating

the good kings in the distant past and the bad ones in the present. When you look over the geographic span of the

bad rulers—from England to Spain to France to Italy to Germany to eastern

Europe, he’s identifying a good three quarters, if not more) of his known world

as ruled by bad kings. You can’t have

more of a condemnation of his existing world than this.

Dante

(the character) is taken aback when he hears Trajan and Ripheus are saved. He had just been told that only baptized

Christians and Old Testament worthies can be saved. How could this be? The eagle answers:

'For from Hell, where no

one may return

to righteous will, the

one came back into his bones --

this his reward for

living hope,

'the living hope that

furnished power to the prayers

addressed to God to raise

him from the dead

so that his will might

find its moving force. (XX.106-111)

First

the eagle alludes to hell where if you recall there was a sign “Abandon hope

all who enter here.” Second the eagle

says that through the “living hope” of prayer—and notice “living hope is

repeated twice—God’s will can find a way to save all righteous people. They still must be baptized—God’s word cannot

be a lie—but our limited sight cannot envision every formulation of God’s

workings. So never give up hope and

never stop praying for anyone you love.

So

why Trajan? Trajan was mentioned in Purgatorio as an example of

humility. It alludes to the story of

Trajan and the widow. Trajan has

gathered an army of a million men and are about to set off on campaign when a

widow stops the column and asks for justice for her murdered son. Trajan wants to ignore her but the widow is

persistent, and Trajan with pity gets off his horse and stops the march until

he can assess justice. He brings justice

to a sorrowful woman, a mater delorosa,

over her murdered son. Well I think you

can see the allusion now.

So

why Ripheus? Who is Ripheus? Ripheus is a less than minor character from

Vergil’s Aeneid, who is briefly

mentioned as a righteous king who dies during the sack of Troy. He is less than obscure. So who can be saved? Everyone from Trajan, the greatest emperor of

the greatest empire, to an obscure, inconsequential name from a thousand years

before the birth of Christ. Who can be

saved? Everyone within the scope of

God’s expansive arms.

###

Some

thoughts on the Saturn cantos.

Saturn

is the final planet in the spheres.

After Saturn will come the sphere of the fixed stars, followed by Prima Mobile, the sphere from which God

controls the universe, and finally the heart of heaven, the Empyrean.

Saturn

contains those who excelled at mystical contemplation. But didn’t we encounter a group of souls who

were mystics in the second garland under the sphere of the sun? Yes, led by St. Bonaventure, but the

distinction is that those at the sun were intellectual mystics. The mystics at Saturn were those who lived

their lives under total mystical immersion into God. The distinction is a subtle one perhaps. The souls at Saturn tend to be monastics, not

friars.

The

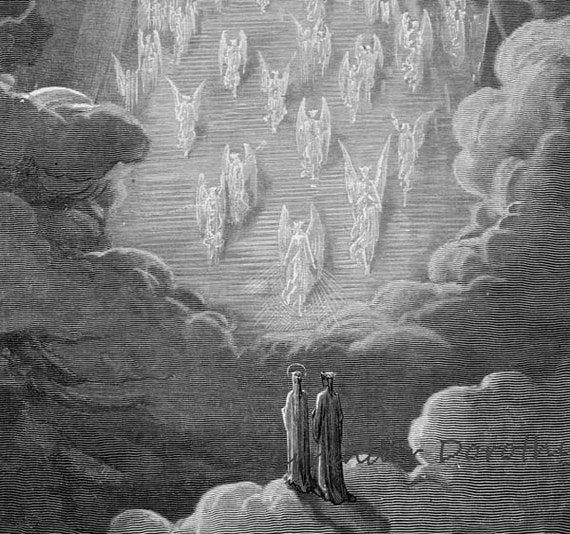

central image in the realm of Saturn is a ladder stretching all the way up to

the Empyrean (if I read correctly) with souls streaming up and down the

ladder. It’s a fantastic image and

worthy of quoting the entire passage.

Within the crystal,

circling our earth,

that bears the name of

the world's belovèd king,

under whose rule all

wickedness lay dead,

the color of gold in a

ray of sunlight,

I saw a ladder, rising to

so great a height

my eyesight could not

rise along with it.

I also saw, descending on

its rungs,

so many splendors that I

thought that every light

shining in the heavens

was pouring down.

And as, following their

native instinct,

rooks rise up together at

the break of day,

warming their feathers,

stiffened by the cold,

and some of them fly off,

not to return,

while some turn back to

where they had set out,

and some keep wheeling

overhead,

just such varied motions

did I observe

within that sparkling

throng, which came as one,

as soon as it had reached

a certain rung. (XXI.25-42)

The

image of the ladder comes from Genesis—Jacob’s ladder—where in a dream Jacob

sees angels ascending and descending between heaven and earth. Here Dante (the author) has souls instead of

angels traversing up and down, and, since they are already in heaven, Dante has

the ladder stretch from Saturn up beyond eyesight toward the end of heaven,

possibly to the Empyrean where God and all souls in heaven reside. The ladder is described as the color of gold

and either emits or reflects sunlight.

The souls going up and down also shine bright, so it makes for a

stunning image.

The

ladder is a perfect image for those immersed in mystic contemplation. What does a contemplative do but rise up to

heaven when in mystical exaltation and return back to earth to share the fruits

of his contemplation? Here at the planet

closest to God, we find souls who minimize rational thought and enjoy God’s

intense grace.

We

see this ever increasing grace through Beatrice’s increasing beauty. If you’ve notice, at each station Beatrice

appears more intensely beautiful, and that’s because the closer the pilgrim’s

travel toward God, the more intense the light that shines, which is allegorical

for increasing grace. Beatrice’s “cup”

filled with grace, is getting filled higher, which was the image I provided in

my comments back in Canto IV to describe a soul’s capacity to receive

grace.

So,

to answer that question I had back in Canto IV, a soul may not be able to

enlarge his cup, but it can get more filled.

Two

saints are featured at Saturn. First is

Peter Damian, a monastic, who was known for his asceticism and

self-mortification. Perhaps an implication

can be drawn that through the self-denial and extreme penance, one climbs the

ladder toward heaven. It’s interesting

he doesn’t come to greet Dante out of willingness but because ultimately he

serves the Lord.

'I have come down the

sacred ladder's rungs this far

only to bid you welcome

with my words

and with the light that

wraps me in its glow.

'It was not greater love

that made me come more swiftly,

for as much and more love

burns above,

as that flaming

luminescence shows,

'but the profound

affection prompting us

to serve the Wisdom

governing the world

has brought about the

outcome you perceive.' (XXI.64-72)

The

mystical ecstasy he feels in God’s bosom overrides his love of neighbor, but he

obeys the Will that moves the world.

That’s a pretty amazing statement, and if you think about it, monastics

is doing just that—separating themselves from society for love of God. But just as in his real life where Damian was

compelled to leave the monastery to become a bishop for society, here too he leaves

the Empyrean to greet the travelers.

The

other featured saint is St. Benedict of Nursia, the founder of the Benedictine

Order, the first major monastic order in the west, and creator of rule that balanced work and prayer. At a time of collapsing civilization the

Benedictines preserved civilization through their monasteries and through

copying of ancient texts. It is the

fruits of contemplation that Dante wishes to emphasize with Benedict.

'I am he who first

brought up the slope

the name of Him who

carried down to earth

the truth that so exalts

us to the heights.

'And such abundant grace

shone down on me

I led the neighboring

towns away

from impious worship that

misled the world.

'All these other flames

spent their lives in contemplation,

kindled by that warmth

which brings

both holy flowers and

holy fruits to birth. (XXII. 40-48)

He

was first to bring Christ up the slope of Monte Cassino and provided the truth

to the neighboring towns for their conversion.

His fellow contemplatives brought down both flowers and fruits from up above. So Peter Damian emphasizes the trip up the

ladder to spiritual ecstasy, St. Benedict emphasizes the trip down the ladder

to bring graces to earth.

Finally

something should be said of the remarkable image of Beatrice and Dante looking

down from high above and first seeing the entire solar system below them and

then finally the little planet earth. This

is akin to the images of space probes we send out to the far reaches of the

solar system to take pictures. Indeed,

the image of the planet earth is equivalent to the famous photos taken by early

space missions where for the first time we had a picture of the earth from the

outside. Dante (the author) was over six

hundred and fifty years ahead of that.

This guy Dante was quite prolific in his writing.

ReplyDeleteGod bless.