Canto

XXIII may be the most beautiful canto in the entire Commedia, and that’s saying a lot.

It’s worth looking at it in a close reading. It’s a canto known for its seven similes, two

simple comparisons, and I’ve noticed a metaphor or two as well. First let me highlight a few of the narrative

details and then I’ll look at each of the seven similes.

We

start the canto with Beatrice suspended in the sky and looking heavenward. She points to Christ above who is in a

triumph. A triumph is a specific ancient

Roman victory celebration where the victorious general is given a public

commemoration. As part of the ceremony,

the man of honor was given a laurel for his head, and, dressed in a golden toga,

took a victory lap in a chariot. That is

how to picture Christ’s triumph. It is a

triumphant ride across the sky, and it also represents the Church

Triumphant. This is one of the three

Church aspects, Militant (in its role to combat sin and heresy), Penitent (in

its role to forgive sins), and Triumphant (in its role to celebrate

salvation). Both Church Militant and

Penitent are roles the Church has on earth; Triumphant is a role in

heaven. The closing quatrain of the

canto summarizes this.

Beneath the exalted Son

of God and Mary,

up there he triumphs in

his victory,

with souls of the

covenants old and new,

the one who holds the

keys to such great glory.

(XXIII.136-139)

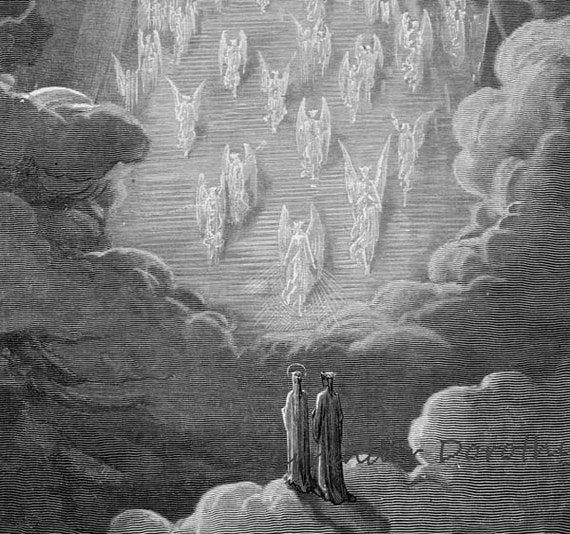

Christ,

in the triumph, is portrayed as bright as the sun. Dante (the character) looking at the intense

brightness goes momentarily blind. This

is the first of the several instances of Dante going blind in this group of

cantos. I’ll have more to say on the

various times he goes blind when I comment on the other cantos, but here the

intensity of Christ’s light is emphasized.

It is notable that it is Christ’s light that illuminates the other

souls, just as the sun illuminates the world.

Beatrice

implores Dante to open his eyes and see her fully. “The things that you have witnessed,” she

says, “have given you strength to bear my smile!” So since he couldn’t see her smile a few

cantos back or he would burnt up, here Dante has graduated to a greater ability

to withstand God’s intensity. He too has

been increasing in grace.

Beatrice

then points to a rose in the heavens, which is the Blessed Virgin. Associated with the rose because of the

flower’s beauty and complexity, the Holy Queen is sometimes called the Mystic

Rose. When the archangel Gabriel comes

down as a lit torch and circles the head of the Blessed Mother, we have the

enactment of her coronation. Is this a

dramatization for Dante’s sake or is this a constant, eternal drama? It doesn’t say, but now every time I get to

the fifth mystery of the Glorious Mysteries of the rosary, I will forever have

this image in mind.

The

drama in this canto is stunning, but let’s look at the poetry through the seven

similes. The first is right at the

opening of the canto describing Beatrice staring at the sky.

As the bird among the

leafy branches that she loves,

perched on the nest with

her sweet brood

all through the night,

which keeps things veiled from us,

who in her longing to

look upon their eyes and beaks

and to find the food to

nourish them --

a task, though difficult,

that gives her joy –

now, on an open bough,

anticipates that time

and, in her ardent

expectation of the sun,

watches intently for the

dawn to break,

so was my lady, erect and

vigilant,

seeking out the region of

the sky

in which the sun reveals

less haste. (1-12)

Now

that is a Homeric type of simile, one sentence of one hundred words (in

English) spanning four tercets. Dante

does not typically write long sentences.

Here we have the bird imagery, which has been a frequent motif throughout

the Commedia, with Beatrice compared

to a mother bird—perhaps foreshadowing the Blessed Mother who will shortly

appear—looking for the sun, which becomes associated with Christ. The mother bird is looking to nourish her

chicks, and Dante is her chick that needs spiritual nourishment.

The

second simile describes how Christ brightens all around him.

As, on clear nights when

the moon is full,

Trivia smiles among the

eternal nymphs

that deck the sky through

all its depths,

I saw, above the many

thousand lamps,

a Sun that kindled each

and every one

as ours lights up the

sights we see above us,

and through that living

light poured down

a shining substance. (25-32)

In

what should be dark night, the sun reflects across to the moon and lights her

up, so Christ lights up all that is around him.

Trivia is an ancient Roman goddess, but I have to admit I don’t get the

allusion and Hollander doesn’t explain it.

The

third simile compares a thought in his mind to a flash of lightning (lines

40-45). The fourth simile compares

Dante’s inability to fully poetically represent Paradise and so requiring a

leap like man walking and needing to leap over an obstruction (61-63). The fifth simile describes how the throng of

souls are lit up like the sun lights up a field of flowers (79-84).

The

sixth simile describes the transcendent beauty of the heavenly music. During the Coronation, heavenly music is

heard and Dante (the author) describes it in an inverse way.

The sweetest melody,

heard here below,

that most attracts our

souls,

would seem a burst of

cloud-torn thunder

compared with the

reverberation of that lyre

with which the lovely

sapphire that so ensapphires

the brightest heaven was

encrowned. (97-102)

So

the sweetest melody heard on earth would sound like a thunder clap compared to

the beauty of the Paradisic melody.

Notice Dante also adds a metaphor as an extension to the simile. That heavenly hymn is a sapphire which

encrowns heaven. The hymn which is a

sapphire which is a crown connects with the crown which circles the Blessed

Mother.

Finally

the seventh simile describes the apostles reaching out to Mother Mary as

infants reaching for their mother.

And, like a baby reaching

out its arms

to mamma after it has

drunk her milk,

its inner impulse kindled

into outward flame,

all these white splendors

were reaching upward

with their fiery tips, so

that their deep affection

for Mary was made clear

to me. (121-126)

The

fiery tips of the splendors, which are souls, are like the arms of a babe

reaching for its mother. Dante brings

mother down to the colloquial, “mamma.”

And what began the canto as a mother bird awaiting to nourish her brood,

it ends with a mother having nourished her babe.

Truly,

what beauty.

###

Here

are some thoughts and comments on the cantos concerning the Starry Sphere.

The

oral examination under which Dante (the character) is subjected is a brilliant

narrative innovation. I can't recall any

other writer writing before Dante to have used it. First off, it captures the university

experience of the medieval world. Next,

it captures the flow of St. Thomas Aquinas' Summa

Theolgiae in which the Commedia owes much philosophically. Here it reproduces it narratively. Also think of the far reaching influence of

this narrative technique. We see such

interrogative dramatizations all the time, most noticeably in crime dramas and

legal suspense stories.

The

oral examination captures the mediaeval university experience so well that it

makes me wonder if Dante (the author) actually attended a university. No such event is recorded. Presumably then Dante had access to many university

texts, especially that of Thomas Aquinas.

The

oral exam also brings one of the ongoing motifs to a conclusion. Throughout the Commedia, Dante (the character) has been learning. He is on a journey to acquire knowledge, and

before he can complete the journey we see what he has learned put to the

test. When lost in the woods of life as

seen way back before he entered the underworld, Dante (the character) was in a

spiritual crises, and what we have seen is that despite having gain great

knowledge of all sorts of things, when Beatrice died he lost his understanding

of the Christian virtues of faith, hope, and charity. Through his journey he has seen what the

three virtues mean, either because they are absent in some (Inferno), struggling to regain in others

(Purgatorio), or celebrated in still

others (Paradiso).

The

spirits that test Dante are the three apostles of Christ's inner circle, saints

Peter, James, and John. Dante

appropriately picks the apostle who in some way was associated with the virtue

they question Dante on. Peter, who

famously denied Christ but had faith enough to walk on water, at least

momentarily, wrote a magnificent letter (First Epistle) on the perseverance of

faith under suffering. St. James, on

whose burial place in Compostella pilgrims go to pray with petitions, examines

Dante on hope, which is what prayer expresses.

And St. John the Evangelist wrote several letters on the virtue of love.

It

is interesting how Beatrice interacts within all three of Dante’s examinations. In her exchange with Peter, she acknowledges

that Peter already knows Dante’s knowledge on faith, hope, and love, but he

should be made to articulate it for God’s glory:

And she: 'O everlasting

light of that great man

with whom our Lord did

leave the keys,

which He brought down

from this astounding joy,

'test this man as you see

fit on points,

both minor and essential,

about the faith

by which you walked upon

the sea.

'Whether his love is

just, and just his hope and faith,

is not concealed from you

because your sight

can reach the place where

all things are revealed.

'But since this realm

elects its citizens

by measure of true faith,

it surely is his lot

to speak of it, that he

may praise its glory.' (XXIV.34-45)

Peter’s

questioning is capped off with a mini credo at the end of the canto

(XXIV.130-147), but the last two tercets capture Dante’s exam answers in two

wonderful metaphors.

The profound truth of

God's own state of which I speak

is many times imprinted

in my mind

by the true instructions

of the Gospel.

'This is the beginning,

this the living spark

that swells into a living

flame

and shines within me like

a star in heaven.' (142-147)

God

is imprinted in his mind through the Gospels, and from that little spark his

faith grows into a flame which shines within him like a star in heaven. Beautiful.

The

canto where Dante (the character) is quizzed on hope, Dante (the author),

intruding into the narrative, begins with an earthly hope.

Should it ever come to

pass that this sacred poem,

to which both Heaven and

earth have set their hand

so that it has made me

lean for many years,

should overcome the

cruelty that locks me out

of the fair sheepfold

where I slept as a lamb,

foe of the wolves at war

with it,

with another voice then,

with another fleece,

shall I return a poet

and, at the font

where I was baptized,

take the laurel crown. (XXV.1-9)

He

hopes that the beauty of this poem, the Divine

Comedy, will someday allow Florence to renounce his exile and allow him

back to receive a laurel crown as poet.

This can be seen in at least two ways.

First, it foreshadows and echoes the canto’s theme of things hoped for,

but it also contrasts his earthly hope with the spiritual hope of

salvation. In fact, it makes the earthly

hope appear so much less in comparison.

When Dante is writing these lines, it is well into his exile and toward

the end of his life. He probably

realized that such a hope would never materialize, and so in a way he is

belittling his pride that he would have such a hope when the hope of eternal

salvation is at hand. Heavenly glory is

by far more important than this earthly glory.

St.

James quizzes Dante on hope. The New

Testament identifies three men as James.

There is James Zebedee, the brother of John, there is another apostle

with the name James, and he is usually referred to as James the Lesser. And in Acts

there is James the head of the church in Jerusalem, who is referred to as James

the Brother of Jesus. James the Lesser

and James the Brother of Jesus are to some considered the same person. But nonetheless this James is not the brother

of John. The James here in the canto is

identified as the one whose bones are in Compostella (18), which indicates that

he is James Zebedee. But when Beatrice

addresses him, as the one “who wrote/of the abundant gifts of our heavenly

court” (29-30), which indicates this is the James who wrote the New Testament

Epistle under his name. But the epistle

was written by the other James if you count two or the Brother of Jesus if you

count three. So Dante is either ignorant

of the distinction or has something in mind by conflating the two. I fail to see any reason for the conflation,

so I lean to a mistake.

Before

Dante provides an answer on what rests his hope, Beatrice interjects that she

knows no other person so filled with hope as Dante (52-54). On what basis does she make this

assertion? Well, think about it. Dante first fell in love with Beatrice when

he was nine years old. He has been

hoping for the fulfillment of this love for many years and across earthly life

and the afterlife. Yes, he has certainly

demonstrated such hope.

Throughout

the questioning from St. John on love, Dante is unable to see. This is the culmination of several instances

of loss of sight while in the Starry Sphere.

The closer Dante journeys to God, the more intense the light. Each time he loses his sight, when he regains

it his eyes are stronger for the next vision.

Each instance is a strengthening, like an exercise.

The

first time he loses his sight in the Starry Sphere is in Canto XXIII when he

looks up to see a vision of Christ triumphant.

When he regains that sight, his eyes are now strong enough to see

Beatrice’s smile. The second time is in

Canto XXV when saints Peter and James stand together and their collective light

overwhelms Dante. James tells Dante to

look up and take hope, and that restores his sight. The third loss of sight in Starry Sphere is

when John approaches and Dante tries to discern if John is in the glory of a

body. The blindness begins at the end of

Canto XXV and stretches all the way through the middle of Canto XXVI when Dante

completes his exam on love without being able to see. It is through the power of Beatrice’s voice

that Dante then regains his sight.

As soon as I was silent,

the sweetest song

resounded through that

heaven, and my lady

chanted with the others:

'Holy, holy, holy!'

As sleep is broken by a

piercing light

when the spirit of sight

runs to meet the brightness

that passes through its

filmy membranes,

and the awakened man

recoils from what he sees,

his senses stunned in

that abrupt awakening

until his judgment rushes

to his aid –

exactly thus did Beatrice

drive away each mote

from my eyes with the

radiance of her own,

which could be seen a

thousand miles away,

so that I then saw better

than I had before. (XXVI.67-79)

Upon

completing his answer, the heavens sound with the Sanctus hymn, and Beatrice’s voice singing along stimulates his

vision like a person being awakened. The

scene alludes to Saul’s transformation to Paul. Just as Ananias of Damascus was

used to restore Saul’s sight (Acts 9:10-18), Beatrice is used to restore

Dante’s sight, whereby now he can see “better” than ever.

The

first thing he sees when he regains his sight is another spirit approaching, this

time Adam. It’s not clear why

narratively Adam approaches now. He

seems out of place with the three apostles, but Dante makes thematic use of it. The first thing Dante sees is the first human

being, and so Dante (the author) gives us a breadth of scope from the beginning

of all time to the present, from the first man to the current. Now only is the timeline linear, but also

circular. Dante’s questions of Adam’s

time seem to emphasize this.

Dante’s

question on the original language is certainly one that would concern a poet,

especially a poet who is writing in the vernacular. Apparently Dante had once believed that

Hebrew was the original language spoken by Adam and Eve, but here we are now

told differently. That original language

has gone extinct, and as Adam implies so does language. This connects with Dante’s vernacular Italian

being the outgrowth of its Latin roots.

Just as Adam is Dante’s “father” here, Adam’s language is ultimately

progenitor to the contemporary languages.

Finally,

Dante’s question of why Adam was expelled from heaven seems curious, since the

Biblical story is well known, but Adam’s answer is even more peculiar. Adam doesn’t say he was expelled for

disobeying God or for eating the apple, which is what we would expect. He says he was expelled for “trespassing”

(XXVI.117). In effect he trespassed on

God’s prerogative. This echoes back to Inferno where Ulysses sails beyond human

boundaries to God’s ire. Adam also

refers to his time away from heaven as an “exile” (116). This connects the two men in their dislocated

histories.