Canto

I

After

Dante (the author, not the character) gives glory to God, he points out that

one who returns from up high can neither fully explain nor fully grasp his

experience, but he will do what he can.

In emulation of the classics, he invokes Apollo, the god of the sun, to

help him in this effort. It is now noon

and Dante (the character) turns to loom at Beatrice, who is staring at the

sun. The light reflecting off her eyes

pours into Dante’s soul so strongly that he can only sustain it for a short

time. But as he continues to gaze on

her, he feels changed within. Through

her, he can see the heavens spinning like wheels, bright as the sun and on

fire. He feels his body lifting and

asks, how could this be? Beatrice

explains that it is natural to be lifted toward the heavens, and that it is

unnatural—because sin is the unnatural state in man—to be held down to earth.

Canto

II

In

a naval metaphor, Dante (the author) warns the reader that not all are fit to

follow him on this journey. Because of

their innate thirst for God, the two pilgrims (Dante the character and Beatrice

his guide) rise with the speed of an arrow shot to the first heavenly sphere,

the moon. Dante asks Beatrice, what do

the dark spots on the moon signify? She

turns the question on him and asks him what he thinks they are. After Dante answers incorrectly, Beatrice

goes on to explain first why he is wrong (it has nothing to do with rare or

dense matter) and second proposes an experiment of mirrors to arrive at the

truth. If the mirrors are staggered,

then a light shining into them appears different size but the original light is

the same for each mirror. The

differences in light and dark coloration on the moon is due to the different

distribution of graces God has used to create the universe, though it’s the

same light that shines on all. It is the

matter which has varying capacity to absorb it.

Canto

III

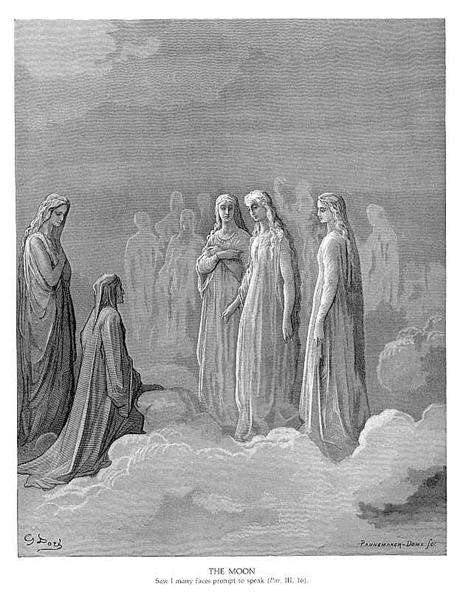

As

Dante was about to confess his error on the moon spots, he sees the outline of

faces as if in the bottom of a pool of water.

The faces are all eager to speak to him.

Beatrice explains to him these beings are assigned under the sphere of

the moon—the moon associated with inconstancy—because they in life failed in

maintaining their vows. She urges him to

speak to them, and he finds the one who speaks back to be his cousin-in-law,

Piccarda, mentioned in Purgatorio (cantos XXIII & XXIV) when Dante met her

brother and his friend, Donato Farese. In

life she had vowed to be a nun but was forced out of the convent by her other

brother to marry for political reasons.

Dante asks her if she is content to be in the lowest sphere of heavenly

blessedness. She responds that she has

no desire for more, that she would not be blessed in the first place if her

will was discordant with God’s. She

replies with the famous line, “In His will is our peace.” She speaks of the spirit beside her,

Constanza, the Empress and wife of Henry VI, who was also pulled out of a

convent to marry. So both have failed in

keeping their religious vows, though both forced. Piccarda then fades into the mist, singing Ave Maria.

Canto

IV

Still

at the sphere of the moon, Dante (the character) is perturbed by two equally

perplexing implications of his encounter with Piccarda. Beatrice reads his mind and formulates for

him the two questions at the root of Dante’s confusion. She answers the second question first by

explaining that these souls do not reside in these heavenly spheres but appear

to him at the sphere as a sign to reflect the distinct heavenly graces that

people receive. These spirits at the

moon reside in Empyrean with all the other spirits in heaven but here reflect

the lower rank they received. This, she

continues, is in complete contradiction to what is generally understood on

earth. He then answers the first

question, pertaining to the justice of people forced from their vows being of

lower rank. It is true, they were

forced, but nonetheless their wills to maintain their vows was incomplete. Their will could have found an escape or even

death to uphold their vows. Satisfied,

Dante asks a third question, can a person make up in some other way for a vow

left unfulfilled? Beatrice looked at

Dante with eyes so radiant that it almost overpowered him.

Canto

V

Beatrice

first addresses Dante's inability to directly look at her, telling him that she

has flamed out more brightly because having moved closer toward God, she has

more perfect vision. Then she

reformulates his question on whether a vow left unfulfilled can be made

up. Beatrice explains that one's free

will given to God in a sacred pledge, one sacrifices further freedom. The only allowable substitution for an unfulfilled

vow must be of a significantly greater vow granted through God's representative,

the Church. She cautions about making

foolish vows. As fast as an arrow shot

the two rise up out of the moon and reach the sphere of Mercury. He sees a number of spirits there as if they

are fish in a pond, and one approaches to speak to him. He tells Dante that he and the spirits around

him are on fire from the light from heaven, and then asks Dante whether he

would like to receive some of this light.

Dante responds that he doesn't know who the spirit is and why he is

under the influence of this sphere. With

apparent joy, the spirit glows even brighter.

No comments:

Post a Comment