I’ve

posted twice on this wonderful book, A. G. Sertillanges’ What Jesus Saw from the Cross, already (here and here) and

I wanted to post one more on its amazing conclusion. I did want to post this before Easter Sunday,

but I was just too busy. But here it is

on Easter Sunday night.

As

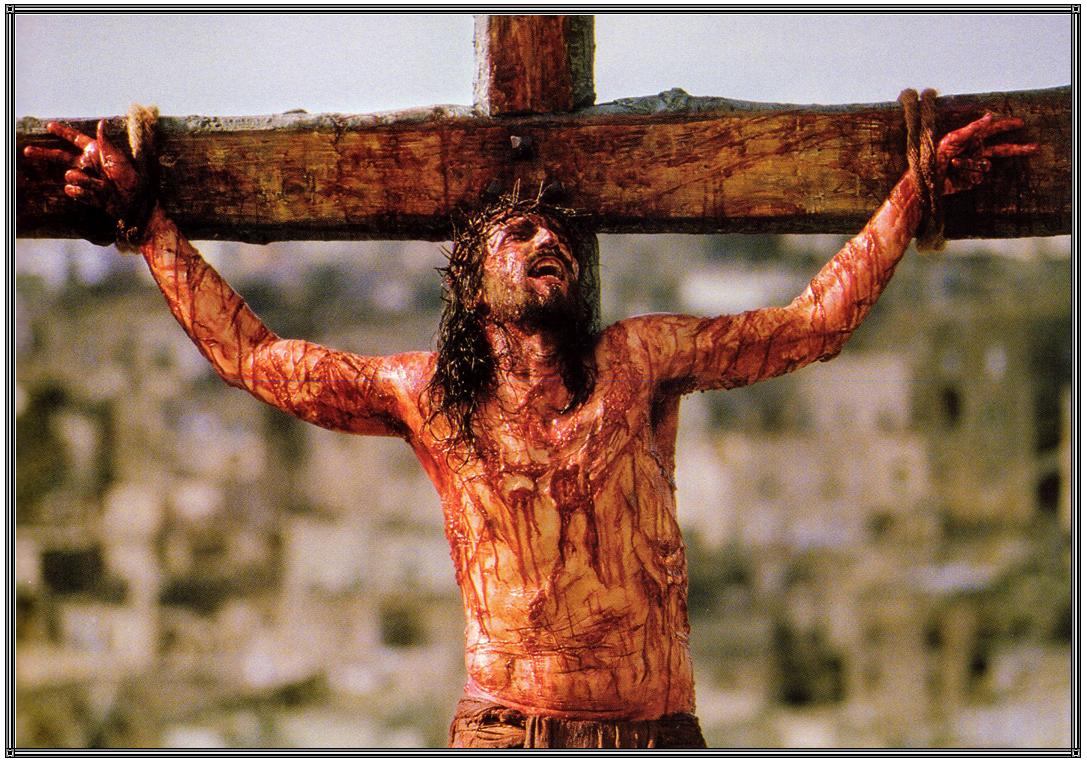

I’ve noted, Sertillanges’ book is a devotional on Christ’s passion, taken from

the perspective of Christ looking out hanging from the cross. Sertillanges identifies the sights and

sounds, the events of Christ’s last days, Christ’s friends and His enemies, His

last words, and what all this sound and fury was about. In the last chapter, as Christ raises His

eyes toward heaven in His last moments of life, the vision steps away from what

is below, and Sertillanges attempts to contemplate Christ’s vision beyond the

earth.

In the eyes of the dying

Savior, things and people are never withdrawn from their natural environment

nor isolated from the divine sphere in which they are enclosed. When He meditates upon what He sees He cannot

but consider its divine content. Heaven

envelopes the earth and all things that are upon it. Lifted up from the earth, more by His soul

than by His Cross, Christ finds in Heaven the first object of His

contemplation. From Heaven He comes and

to Heaven He returns. Thus it is with

His eyes raised to Heaven that we must think of Him uttering His first and His

last sentences, each of them beginning with the word Father. (p.211)

Two

things are important there—the intermingling of the divine with the material

and the source of the first cause, God the Father. In that glance toward the Father, eternity

and the temporal meet, and the mutual love of the Father and Son, which blossoms

in the form of the Holy Spirit, is made manifest. What Sertillanges sees at that moment is the

reconciliation of all things, the material and the spirit, the eternal and the

transient, the internal and the external.

It is not without importance

at the foot of the Cross, which reconciles all extremes, to notice how the heavens—especially

the heavens at night—are related to the mystery of the soul. The ether is beyond all measure; and beyond

all measure and understanding also are the stirrings of the heart. We cannot rise to the stars or descend to the

depths of our being. Two infinites

stretch beyond the bounds of our experience, and both attract us irresistibly

yet hold us at a distance.

What can we do without

God in the heights, and without His grace in the depths of ourselves? Yet we feel that these two domains coalesce

and that God, who is in us and ineffably beyond us, welds the whole of nature

into one. If we go to God and give

ourselves to Him, then we reconcile all things—being, our own being, and the

Subsistent Being upon whom all else depends.

(pp. 213-14)

Reconciliation implies that despite

fragmentation there is unity. Christ

being one of the Trinity is aware of the impalpable wholeness. Sertillanges continues:

We cannot doubt that

Christ always has an intimate realization of these things. If “the father had given all things into His

hands” (John 3:35), it was assuredly with the full consciousness that this was

so. Filled with the knowledge of what

is, He has by that very fact full assurance of what He does. His vision reaches unerringly to God, the

living Heaven, to the soul, that lowly heaven in which the other is reflected,

to the nature of the universe, and to Himself in whom all these fragments of

reality find their unity.

And

so Sertillanges has Christ first lovingly contemplating the beauty of creation,

the natural world, the blue vault of sky, the gathering clouds, expressing that

vision in His imagination as a poet expresses mystery. Here Christ becomes an artist, expressing

truth and beauty, all leading to God and a part of God.

Who better than this

human and heavenly soul was able to taste God in the universe and the universe

in God who sustains it? Associated with

the divine harmony (One in Three, Three in One), is He not wholly attuned to

the music of creation? Son of Man, does

He not find in man’s dwelling place His proper home? He has caught up in Himself the whole of

humanity. He bears within Himself the

Idea, the begetter of beings. He is the “beginning

of creation of God” (Rev 3:14) and He is the End. Everything is a symbol of Him. Nature tends to Him with all its significance

and all its powers. (pp. 216-17)

In

that last moment Christ “perceives the harmony of creation as an eternal Will

whose applications to human life for the object of His teaching, of His

exhortations, and of His grace. He

mingles Heaven with earth, nature with the soul, time with the eternal outcome

of time” (217). Christ both contemplates

the vastness of the grand universe and the minuteness of the molecular world,

the infinity inside the microscopic. His

vision is both expansive and confined.

Second,

Setillanges has Christ, at that moment of looking heavenward, in prayer on the

cross. Christ’s contemplation of the

harmony of all things is a prayer.

Jesus prays. His prayer on the Cross is a continuation of

His constant prayer. If the sky is

Heaven, if the universe, the soul, and God are Heaven, then the act by which

Jesus links all of these together in one common thought is a communion with Heaven

in the most complete sense of the word, a vision of Heaven boundless and

sublime. (p. 220)

It

is in prayer that the sublime of Heaven interfuses with the physicality of

earth, the transcendence of the spirit with the incarnate of flesh and blood. The cross is the axis between the two realms.

The cross, then, is the

great place of prayer, just as it is the great altar, the great monstrance, and

the first tabernacle. It is not in vain

that we are told to begin and end prayer with the sign of the Cross. Properly understood the sign means: “I adore

Thee, my God, by the Cross, by Jesus on the Cross, with Jesus on the Cross, in

a spirit of commemoration and trust, but also in a spirit of obedience and

sacrifice…I ask of Thee all that I need in the name of the Cross, that is, in

the name of the same memory, in the name of the same merits, to which I humbly

unite those things that are wanting, according to the exhortation of the

Apostle” (Col 1:24). (pp 224-25)

Paul

in that passage in Colossians speaks of uniting his sufferings with that of

Christ. Sertillanges is suggesting that

through such a union, we too marry the transcendence with our flesh and

blood. We reach it through prayer and

sacrifice, which amounts to love. Jesus

prays on the cross the 22nd psalm, “My God, my God, why hast Thou

forsaken me.” We all know the famous

first line, but surely Christ didn’t stop praying there. He prayed the whole psalm, and in it we hear of

the suffering servant but we also hear of the transcendent. By the middle of the psalm, the psalmist

gives praise to the Lord, and by the conclusion the Lord is triumphant. The dualism of suffering and victory merge,

as does Christ on the cross.

In Christ there are two

lives, the one is a temporal life, which moves on from the manger to the Cross

and the grave, the other eternal, immutable at the right hand of the

Father. The Beatific Visio, identical in

each, welds as it were these two lives in one.

For Jesus, life after death is not entirely a renewal; it is a

continuation. Jesus is reborn and

glorified in His flesh; but in His soul He merely pursues His destiny and

continues His eternal colloquy with God.

The crown of His destiny makes no deep change in Him. In the dust of daily action, and under the

searing fire of pain, He was already in glory; He saw God face-to-face. What was there still for Him to acquire, save

that His body should finally share the glory of His soul. (p. 230)

So

in that moment of looking toward heaven, just before Christ dies, defeat and

victory, heaven and earth, spirit and body, fuse. Sertillanges has Jesus watching the heavens

open. “This is His vision of victory,

symbolized on Calvary by those eyes that look out upon the infinity of space

through a film of blood” (pp. 233-34).

This

is a remarkable book, one of the best devotionals—if not the best—I have ever read.

I

hope your holy week was blessed and Easter Sunday joyous. Alleluia, He is risen.

Thank you Manny for taking the time to write this post.

ReplyDeleteWishing you all the best to you and your family this Easter.

God bless you all always.

Happy Easter and God Bless, Manny!

ReplyDeleteManny I came for a quick look but when I saw The Cross...

ReplyDeleteLong story short ...What a beautiful read.

God Bless All His Children and why some still don't believe in "The Risen Christ" is beyond Christian understanding.

God Bless you and yours on this Easter Monday.

Thank you all for stopping by. Have a great Easter season.

ReplyDelete