This is Post #3 of Henryk Sienkiewicz’s historical

novel, Quo Vadis.

You can find Post #1 here.

And Post #2, here:

Chapters 15 thru 20

Summary

The narrative suddenly turns epistolary. First Petronius sends a letter to Vinicius that he and the Roman aristocracy are in the vacation town of Antium. He provides some of the gossip and some of the machinations between rivals. He mentions that the pain of little Augusta’s death is still fresh. Vinicius, in Rome, writes back that despite Chilo’s clandestine excursions into the Christian population, Lygia has not been found. Chilo has brought back information that the Christians have prayer services in meeting houses. He tells Petronius that he too in disguised has wandered to some of the prayer houses.

The narrative returns with Chilo having been away from Vinicius for some time, and Vinicius’ emotions toward Lygia gone from love to anger, but he strengthens his resolve to find her and possess her. Finally after some time Chilo returns to tell him though she has not been found she is certainly among them. Chilo mentions that he has found an old nemesis, an old man named Glaucus who was responsible for Chilo losing two fingers on his hand and that he had left him at an inn dying of stab wounds after Glaucus’ wife and child were abducted. He says that robbers had done this to Glaucus, and now Glaucus had apparently joined the Christians. Vinicius asks him why this should concern him, and Chilo says he must stay away from Glaucus and can no longer search for Lygia. Vinicius is enraged and says he will kill Chilo himself if he doesn’t continue. Chilo reluctantly agrees but requests money to have Glaucus killed. Vinicius advances him a good portion of Chilo’s fee. Chilo reveals that a certain Paul of Tarsus, a Christian lawgiver, is due to come to Rome and hopes that he can locate Lygia in that gathering.

Chilo again goes undercover to the Christian he has befriended, the old man Euricius. Chilo explains his need for protection, and Euricius’ son Quartus puts Chilo in contact with Demos who is supposed to have laborers who can work as bodyguards. Among the laborers is a gigantic man named Urban. Chilo explains to Urban how this man named Glaucus plans to betray the Christians and must be killed. Chilo couches the story into a replay of Judas betraying Christ, and that Glaucus is a second Judas. Urban tells Chilo he will do it despite that he feels guilt still for killing another man accidently. Urban also tells Chilo of a big Christian gathering at Ostrianum, the cemetery outside the city gates. There a great apostle of Christ is supposed to give a talk and all the Christians will be there. There Urban says he will to kill Glaucus.

Petroinus writes another letter to Vinicius. He tells Vinicius to hire Croton to be his guard as he wanders the streets of Rome. He will be needed to defend against Ursus when Lygia is found. He goes on about more political gossip and winds up that at some point he may slice his veins to end his life.

Chilo barges into Vinicius’ home to tell him that he has found Lygia. He has not exactly found her but knows where she will be that evening. She will be at Ostrianum with Ursus who has changed his name to Urban. Chilo cowardly says he will not join Vinicius that evening, but Vinicius compels him with money and with the company of Croton. Vinicius now is in wild delight. He will finally possess Lygia. Chilo explains how Ursus is supposed to kill Glaucus, but wonders if the goodness of Christianity will dissuade Urban. Chilo explains the Christian God is one of morality. They all put on cloaks with hoods and head off to Ostrianum.

At Ostrianum they watched the Christians slowly gather

in huge numbers. Vinicius noticed that

the Christians relate to their God with love, unlike any religion he had ever

seen. He did not love his Greco-Roman

gods but feared them. He listened to the

Christians sing hymns. Finally an old

man named Peter stepped up on a rock and blessed the crowd with the sign of a

cross. They heard the old man had been a

fisherman once and had been Christ’s chief disciple. Peter began to speak like a father

instructing his children, imploring them to be good and pure. Vinicius notices that Christianity is

different from any philosophy he knows.

Peter even speaks on the merits of suffering and even death like that of

Christ. Vinicius is repelled by this

teaching. What kind of God is this? He concludes that Christianity is

madness. Peter goes on to speak of his

witness to Christ, of Christ’s death and how they had found the tomb empty and

ultimately come across the Risen Christ.

Vinicius became lost in Peter’s narrative and was torn between belief

and unbelief. Peter kept saying, “I

saw.” As morning began to rise, Chilo

pulled Vinicius aside and pointed to Urban and the girl. Vinicius turned and saw Lygia.

###

My

Comment:

Oh my! Was that a spectacular Chapter 20? I was glued.

Madeleine

Replied:

I agree, Manny. I'm finding it harder to put down, and really easy to keep up so far. Even though I read it when I was in high school, I really didn't remember much, so it's a whole new book this time.

My

Comment:

What is interesting is that Sienkiewicz waited for almost a third of the novel to get to the Christians. Up to now we've barely seen the Christians interact and the anticipation climaxed with St. Peter's sermon. That was highly skilled plotting.

Michelle

Replied:

When I knew that St. Peter was about to come onstage I was thrilled!

Joseph

Replied:

I agree with Manny on the clever construction of the narrative. Sienkiewicz has gone the extra length to make early Christians seem mysterious to the modern Christian, or at least culturally Christian, people reading the book and having to place themselves in the viewpoint of 1st century Romans.

Galicius

Commented:

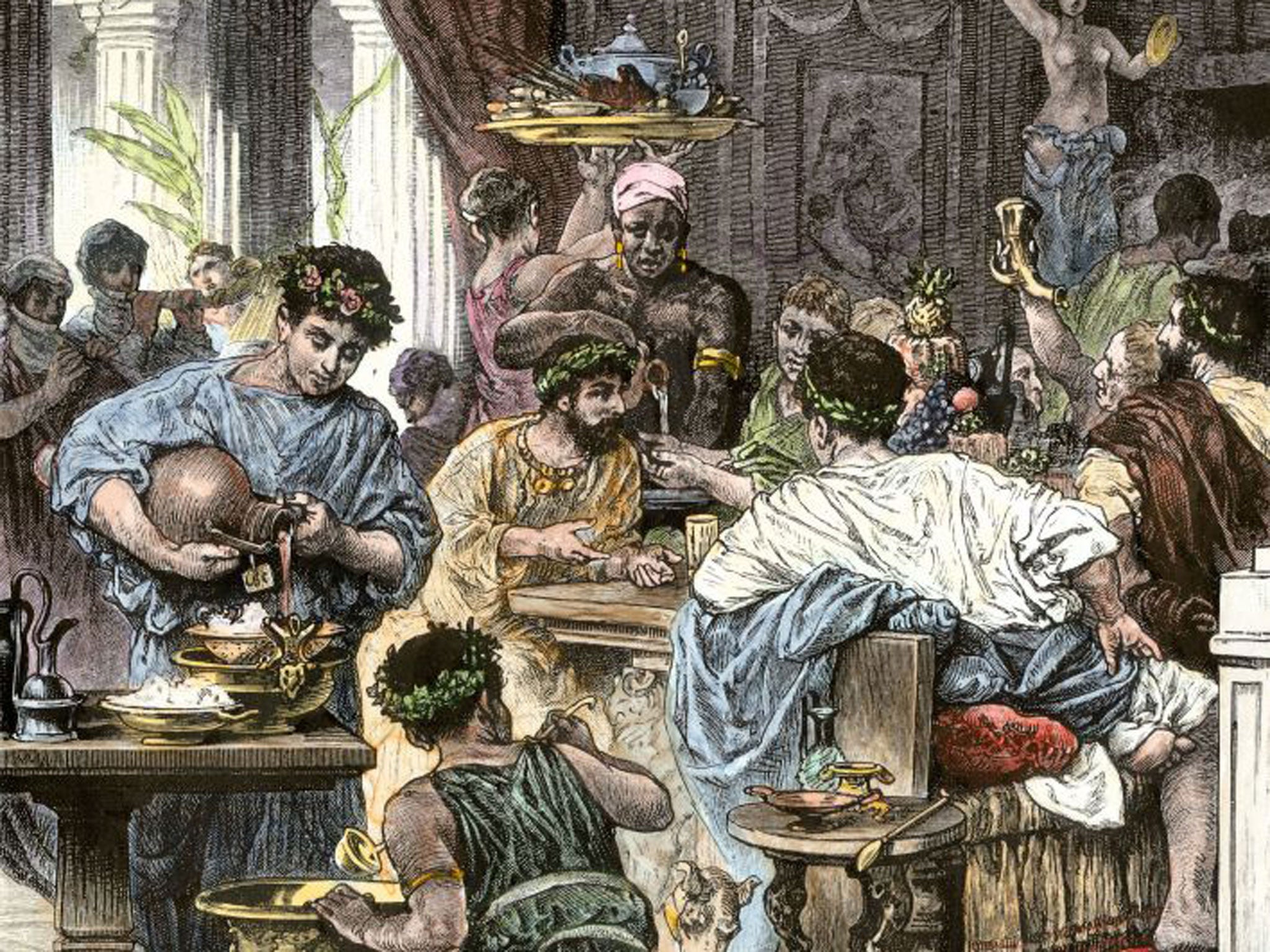

It seems that Sienkiewicz set himself a goal to present mutual relationship of two worlds pagan—Roman—and Christian. Sienkiewicz was criticized that his portrayal of Christianity pales compared to the pagan world in all its splendor of Roman palaces and life of its citizens, Caesar and his court. We get another description soon of a feast hosted by Tigellinus for Caesar in Chapter XXXI. It seems to me though that this is to be expected. Christians in Rome during Nero had to hide underground. How was Sienkiewicz to portray them in material terms? Christianity as seen by Vinicius in Lygia is perhaps best explained in Chapter XXXIV: “that beauty of a new kind altogether was coming to the world in her, such beauty as had not been in it thus far; beauty which is not merely a statue, but a spirit.” (Sorry for moving ahead but I do not think I am giving away anything of the story.)

Michelle

Replied to Galicius:

He might be showing more of the Roman world, but he also shows how empty it is. Vinicius seems to be more discontent with Rome as the story continues.

My

Reply to Galicius:

Yes, it seems he is setting out to contrast two world views, but I would disagree with those that claim the Roman world is presented in splendor. Yes, there are riches and power dramatized but I think it presents the Roman world as a bunch of overindulgent egotists who only care about themselves. The old Roman virtues of nobility and piety are long gone and what is left in this post Republican world is self-centeredness and hedonism. I don't find this a positive portrayal of the Roman world. It also feels very true.

Galicius

Replied:

My above remarks were misunderstood—as if Sienkiewicz was representing Roman culture positively and purposely belittling the faithful Christians. We will see that this plebeian Christian culture that is depicted as little and pale compared to the aristocratic and powerful official patricians will be victorious in the end. Remember that God and Ursus is with them.

Madeleine’s

Comment:

I am liking the rich detail in the novel. Sienkiewicz does bring his characters to life while giving us the context that envelops their lives. The pagans are definitely more sensually oriented than the Christians, and I like how Vinicius gradually begins to understand what is missing in the pagan world. Will he give himself over to Christ and will he be able to love Lygia with a holy Christian love? Suspense building here.

Kerstin’s

Comment:

The roller-coaster of emotions Vinicius goes through in chapter 16 seems excessive to our sensibilities. Here is a young Pagan man who has yet to encounter the meaning of "love your neighbor as yourself". Ligyia is more object to him rather than a person.

My

Reply to Kerstin:

I thought so too at first but that's where I saw Sienkiewicz building the psychologies of the pagan world (with its variety) and the Christian world. I am marveling at how the author is capturing the psychology of the pagan world.

Frances’s

Comment:

I’d like to recommend Tom Holland’s excellent study of ancient cultures here. The title is Dominion (with a superb reproduction of Dali’s ‘’Christ of St. John of the Cross” on its cover). In it Tom Holland writes of his awakening to the cruelty of the ancient world: “The more you study the world of the ancient Romans the more alien they seem to be. Theirs was a culture built on systematic exploitation, an economy founded on slave labor,” and — to Kerstin’s point — “the absolute right of free Roman males to have sex with anyone they wanted and in any way they wanted . . . ‘’

My

Reply to Frances:

I have thought of this

book too while reading Quo Vadis. The central thesis of Holland's historical

book is that there was a stark and lasting change in the world

views/psychologies of the pagan world and the Christian world. I have not read

this book but I have read reviews and heard Holland interviewed.

This is Holland's book Dominion: How the Christian RevolutionRemade the World. I bet you can find interviews of Holland on YouTube.

Frances’s

Reply:

Thank you, Manny. One of

the best interviews I’ve found on YouTube is “Unbelievable? Tom Holland and Tom

Wright: How St. Paul changed the world.” A conversation you’ll want to listen

to again and again.

###

Excerpts

from chapter 20. Vinicius and Chilo

sneak into a Christian ceremony in the middle of the night and witness Peter giving

a homily. I’m going to split this into

two parts. First Vincius’s observations

of the Christian ceremony.

Vinicius had seen a

multitude of temples of most various structure in Asia Minor, in Egypt, and in

Rome itself; he had become acquainted with a multitude of religions, most

varied in character, and had heard many hymns; but here, for the first time, he

saw people calling on a divinity with hymns,—not to carry out a fixed ritual,

but calling from the bottom of the heart, with the genuine yearning which

children might feel for a father or a mother. One had to be blind not to see

that those people not merely honored their God, but loved him with the whole

soul. Vinicius had not seen the like, so far, in any land, during any ceremony,

in any sanctuary; for in Rome and in Greece those who still rendered honor to

the gods did so to gain aid for themselves or through fear; but it had not even

entered any one's head to love those divinities.

Though his mind was

occupied with Lygia, and his attention with seeking her in the crowd, he could

not avoid seeing those uncommon and wonderful things which were happening

around him. Meanwhile a few more torches were thrown on the fire, which filled

the cemetery with ruddy light and darkened the gleam of the lanterns. That

moment an old man, wearing a hooded mantle but with a bare head, issued from

the hypogeum. This man mounted a stone which lay near the fire.

The crowd swayed before

him. Voices near Vinicius whispered, "Peter! Peter!" Some knelt,

others extended their hands toward him. There followed a silence so deep that

one heard every charred particle that dropped from the torches, the distant

rattle of wheels on the Via Nomentana, and the sound of wind through the few

pines which grew close to the cemetery.

Chilo bent toward

Vinicius and whispered,—"This is he! The foremost disciple of Christ-a

fisherman!"

The old man raised his hand, and with the sign of the cross blessed those present, who fell on their knees simultaneously. Vinicius and his attendants, not wishing to betray themselves, followed the example of others. The young man could not seize his impressions immediately, for it seemed to him that the form which he saw there before him was both simple and uncommon, and, what was more, the uncommonness flowed just from the simplicity. The old man had no mitre on his head, no garland of oak-leaves on his temples, no palm in his hand, no golden tablet on his breast, he wore no white robe embroidered with stars; in a word, he bore no insignia of the kind worn by priests—Oriental, Egyptian, or Greek—or by Roman flamens. And Vinicius was struck by that same difference again which he felt when listening to the Christian hymns; for that "fisherman," too, seemed to him, not like some high priest skilled in ceremonial, but as it were a witness, simple, aged, and immensely venerable, who had journeyed from afar to relate a truth which he had seen, which he had touched, which he believed as he believed in existence, and he had come to love this truth precisely because he believed it. There was in his face, therefore, such a power of convincing as truth itself has. And Vinicius, who had been a sceptic, who did not wish to yield to the charm of the old man, yielded, however, to a certain feverish curiosity to know what would flow from the lips of that companion of the mysterious "Christus," and what that teaching was of which Lygia and Pomponia Græcina were followers.

Second excerpt is part of Peter’s homily.

The old man closed his

eyes, as if to see distant things more distinctly in his soul, and

continued,—"When the disciples had lamented in this way, Mary of Magdala

rushed in a second time, crying that she had seen the Lord. Unable to recognize

him, she thought him the gardener: but He said, 'Mary!' She cried 'Rabboni!'

and fell at his feet. He commanded her to go to the disciples, and vanished.

But they, the disciples, did not believe her; and when she wept for joy, some

upbraided her, some thought that sorrow had disturbed her mind, for she said,

too, that she had seen angels at the grave, but they, running thither a second

time, saw the grave empty. Later in the evening appeared Cleopas, who had come

with another from Emmaus, and they returned quickly, saying: 'The Lord has indeed

risen!' And they discussed with closed doors, out of fear of the Jews.

Meanwhile He stood among them, though the doors had made no sound, and when

they feared, He said, 'Peace be with you!'

"And I saw Him, as

did all, and He was like light, and like the happiness of our hearts, for we

believed that He had risen from the dead, and that the seas will dry and the

mountains turn to dust, but His glory will not pass.

"After eight days

Thomas Didymus put his finger in the Lord's wounds and touched His side; Thomas

fell at His feet then, and cried, 'My Lord and my God!' 'Because thou hast seen

me thou hast believed; blessed are they who have not seen and have believed!'

said the Lord. And we heard those words, and our eyes looked at Him, for He was

among us."

Vinicius listened, and

something wonderful took place in him. He forgot for a moment where he was; he

began to lose the feeling of reality, of measure, of judgment. He stood in the

presence of two impossibilities. He could not believe what the old man said;

and he felt that it would be necessary either to be blind or renounce one's own

reason, to admit that that man who said "I saw" was lying. There was

something in his movements, in his tears, in his whole figure, and in the

details of the events which he narrated, which made every suspicion impossible.

To Vinicius it seemed at moments that he was dreaming. But round about he saw

the silent throng; the odor of lanterns came to his nostrils; at a distance the

torches were blazing; and before him on the stone stood an aged man near the

grave, with a head trembling somewhat, who, while bearing witness, repeated,

"I saw!"