This

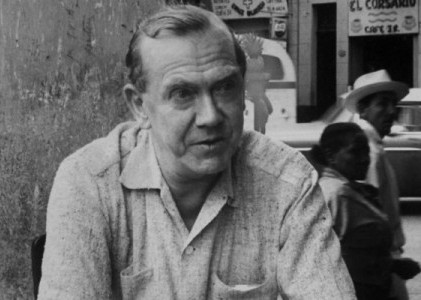

is the third post on my reading of Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory.

You

can read Post #1 here.

Post#2

here.

Another

important pairing is the priest with Coral Fellows. Coral is thirteen, just prior to

puberty. But she is profoundly

intelligent, precocious in her empathy, and maybe even prescient in the sense

that she seems to understand things in a way beyond limitations. When her mother tells her father Coral has

been entertaining a policeman at the house, her father goes to interrogate

her. Here’s her introduction to the

scene.

She stood in the doorway

watching them with a look of immense responsibility. Before her serious gaze

they became a boy you couldn’t trust and a ghost you could almost puff away, a

piece of frightened air. She was very young—about thirteen—and at that age you

are not afraid of many things, age and death, all the things which may turn up,

snake-bite and fever and rats and a bad smell. Life hadn’t got at her yet; she

had a false air of impregnability. But she had been reduced already, as it

were, to the smallest terms—everything was there but on the thinnest lines.

That was what the sun did to a child, reduced it to a framework. The gold

bangle on the bony wrist was like a padlock on a canvas door which a fist could

break. (p. 33)

She

carries an air of responsibility (her parents stand as a “boy” before, that is

she becomes their parent), is unafraid, and “reduced” from the sun which I take

to mean thin and smallish. But she comes

across as “impregnable” because “life hadn’t got at her yet.” Despite her intelligence and sense of

responsibility—after all she takes care of her emotionally debilitated

mother—there is a quality of innocence.

All these qualities and with perhaps a certain providential grace, she

understands and gets correct the moral situation before her. She keeps the priest hidden from the police.

What

we learn is that she has lied to the lieutenant about a priest on their property

and has hidden the priest while kept the lieutenant at bay. It is through her directives that first she

resolves the situation with the lingering policeman, then explains to her

father there really is a priest hidden, and finally she takes her father to

him. The father has absolutely no

empathy for the priest. He is the exact

opposite of Coral, refusing to give him drink and food, and insists he leave as

soon as it gets dark.

What

is astonishing is that the “politics” of the situation is completely irrelevant

to Coral. As they are walking to the

barn, her father snaps at the girl, “We’ve no business interfering with

politics.” But Coral responds: This

isn’t politics. I know about politics. Mother and I are doing the Reform Bill”

(37). Her father is completely

configured to the politics. Coral is

configured differently. So she sneaks

back out later.

Coral put down the

chicken legs and tortillas on the ground and unlocked the door. She carried a

bottle of Cerveza Moctezuma under her arm. There was the same scuffle in the

dark: the noise of a frightened man. She said, ‘It’s me,’ to quieten him, but

she didn’t turn on the torch. She said, ‘There’s a bottle of beer here, and

some food.’

‘Thank you. Thank

you.’

‘The police have

gone from the village—south. You had better go north.’

He said nothing.

She asked, with

the cold curiosity of a child, ‘What would they do to you if they found you?’

‘Shoot me.’

‘You must be very

frightened,’ she said with interest.

He felt his way

across the barn towards the door and the pale starlight. He said, ‘I am

frightened,’ and stumbled on a bunch of bananas. (39)

She

feels his hunger, and feeds him secretly.

Not only has she lied to the police, she has disobeyed her father. Why?

She doesn’t really know whether he’s innocent. She helps him because there is a suffering

man who seems to have his dignity reduced.

If the whisky priest is on a passion narrative in this novel—and that is

one way to look at the story—Coral is Veronica wiping the face of Jesus at the

sixth station of the cross. Her reaction

when he tells her of the consequences of being caught is empathy: “You must be

very frightened.” She looks into his

heart and connects with it. The politics

of the world crumble when faced with the humanity before her.

They

continue this heart to heart conversation.

At one point she offers a solution to his situation.

She said, ‘Of course you

could—renounce.’

‘I don’t understand.’

‘Renounce your faith,’

she explained, using the words of her European History.

He said, ‘It’s

impossible. There’s no way. I’m a priest. It’s out of my power.’

The child listened

intently. She said, ‘Like a birthmark.’ (40)

“Like

a birthmark,” she intuits the sacrament of Holy Orders. Like Baptism, Holy Orders is a mark on your

soul that cannot be taken away (see Ps 110:4 “The Lord has sworn and will not waver:

"You are a priest forever in the order of Melchizedek” and echoed in Heb

7:17). She understands his existential

predicament. And so she offers him to

return any time to hide out. She tries

to tech him Morse code and asks him when he comes to signal with two longs and

one short (41). It is interesting that

two longs and one short in Morse code stand for the letter “G.” Why “G”?

Perhaps standing for God?

The

conversation then turns toward God. He

asks her if she believes in God, and she says she has “lost her faith” at the

age of ten. Here now it is the whisky

priest’s turn to talk to her heart. He

tells her twice he will pray for her and gives her hope that with a little

brandy he can “defy the devil.”

.jpg)

The priest speaks in this language of the heart,

and all the characters respond in some measure also with their hearts, but that

measure is perhaps a level of grace granted to the character. Mr. Tench receives the language of the heart

and is touched enough to break his apathy and write to his wife, who writes

back granting him a divorce. He is

touched enough to feel the heartache of the priest’s death at the end of the

novel.

Coral responds the most, as I’ve pointed out

here. Later we see she has been touched

by the priest when she brings up God and faith to her mother. The priest’s conversation, heart, and,

indeed, his prayers have been working on the girl. In his dream of the night before the

execution, the priest dreams of Coral.

She is there at the feast in heaven, where he sees himself eating

hungrily just like he did when Coral fed him in the barn. In the dream she, who we learn in the course

of the novel has died, taps out Morse code for the priest. Notice also that in heaven she taps out

differently than what she proposed in the barn.

In the dream she taps out three longs and one short. There is no single letter in Morse code for

three longs and a short. Three longs

stand for “O” and one short stands for “E.”

I could be off base here but could those be the vowels surrounding the

word “love”? Of course that’s

speculation, but the one thing for sure is that she communicates with him from

heaven. Heart speaks to heart.

###

The

next paired conversation with the whisky priest that leads to more insight of

the novel is that with Brigitta, his illegitimate daughter. Of all the people in the entire novel, we

know that Brigitta is special to him. It

is almost the first thing he brings up when he comes to his village and sees

her mother, Maria.

He said gently, not

looking at her, with the same embarrassed smile, ‘How’s Brigitta?’ His heart

jumped at the name: a sin may have enormous consequences: it was six years

since he had been—home.

‘She’s as well as the

rest of us. What did you expect?’

He had his satisfaction,

but it was connected with his crime; he had no business to feel pleasure at

anything attached to that past. (p.

61-62)

And

so we see here the paradox of pain and joy.

Later children come by to kiss the hand of a priest, and he looks for

his daughter among them, though he has no idea what she looks like.

The real children were

coming up now to kiss his hand, one by one, under the pressure of their

parents. They were too young to remember the old days when the priests dressed

in black and wore Roman collars and had soft superior patronizing hands; he

could see they were mystified at the show of respect to a peasant like their

parents. He didn’t look at them directly, but he was watching them closely all

the same. Two were girls—a thin washed-out child—of five, six, seven? he

couldn’t tell, and one who had been sharpened by hunger into an appearance of

devilry and malice beyond her age. A young woman stared out of the child’s

eyes. He watched them disperse again, saying nothing: they were strangers. (62-63)

The

continuity of faith between generations has been atrophied. They don’t know the significance of a priest

now that the persecution has been going on since before they were born. It is the girl with the appearance of devilry

that turns out to be his daughter. In

her eyes he sees a “young woman,” not a child.

It is also important to note that he attributes hunger (the “one who had

been sharpened by hunger”) for what I’ll call a loss of innocence. Yes, she is only seven but there is a lack of

innocence in Brigitta that was there with Coral who was twice her age. In fact, when the priest has a moment of

personal anguish, it is Brigitta who laughs at him. The anguish is in reaction to hearing that a

man was executed from not turning in the priest.

He gave a little yapping

cry like a dog’s—the absurd shorthand of grief. The old-young child laughed. He

said, ‘Why don’t they catch me? The fools. Why don’t they catch me?’ The little

girl laughed again; he stared at her sightlessly, as if he could hear the sound

but couldn’t see the face. Happiness was dead again before it had had time to

breathe; he was like a woman with a stillborn child—bury it quickly and forget

and begin again. Perhaps the next would live.

(63-64)

At

this point he still doesn’t know that this is his daughter. Later he specifically asks for her.

He said shyly, ‘And

Brigitta … is she … well?’

‘You saw her just now.’

‘No.’ He couldn’t believe

that he hadn’t recognized her. It was making light of his mortal sin: you

couldn’t do a thing like that and then not even recognize …

‘Yes, she was there.’

Maria went to the door and called, ‘Brigitta, Brigitta,’ and the priest turned

on his side and watched her come in out of the outside landscape of terror and

lust—that small malicious child who had laughed at him. ‘Go and speak to the

father,’ Maria said. ‘Go on.’

He made an attempt to

hide the brandy bottle, but there was nowhere … he tried to minimize it in his

hands, watching her, feeling the shock of human love. (65)

“The

shock of human love” is what makes the priest transcend his sins. It is his love for all humanity—not just in a

general sense but with every specific human being—that makes him a true

Christian. Jesus commands us to love our

neighbor, but it is John in his first epistle that describes it as more than a

commandment but of a thing of the heart.

Beloved, let us love one

another, because love is of God; everyone who loves is begotten by God and

knows God. Whoever is without love does

not know God, for God is love... Beloved, if God so loved us, we also must love

one another. No one has ever seen God.

Yet, if we love one another, God remains in us, and his love is brought to

perfection in us…We have come to know and to believe in the love God has for

us. God is love, and whoever remains in

love remains in God and God in him. In

this is love brought to perfection among us, that we have confidence on the day

of judgment because as he is, so are we in this world. There is no fear in love, but perfect love

drives out fear because fear has to do with punishment, and so one who fears is

not yet perfect in love. We love because

he first loved us. If anyone says, “I

love God,” but hates his brother, he is a liar; for whoever does not love a

brother whom he has seen cannot love God whom he has not seen. This is the commandment we have from him:

whoever loves God must also love his brother.

(1 Jn 4:7-21)

It

is a long passage, and though I took out part through ellipses, but I think

that passage is central to the novel. It

is through being in God’s love that makes us love, and then there is no room

for hate. You cannot hate your fellow

human being if you are in God’s love.

But there is an implied corollary from this as well. How can you love your brother in general if

you don’t love someone specific? Love of

brother is not an abstraction of general humanity, but of specific persons.

Here

the whisky priest loves his daughter in this specific way. And so he feels that “shock” of love. His

empathy goes out to her. He protects her

against her mother’s castigation (67) and wants to show her magic tricks

(68). He wants to come down to her level

and speak heart to heart. The child’s

impudence prevents him. Still the child

saves his life when the lieutenant enters the town and child identifies him as

her father, which should rule out being a priest (76). Later he tells Maria “The next Mass I say

will be for her” (79). The priest has

one more conversation with Brigitta after the lieutenant leaves. At the garbage heap while looking for his

thrown out papers, the child comes to him.

They talk heart to heart. She

tells him “they laugh at her” and that “everyone else has a father” (81). He is taken aback.

He was appalled again by

her maturity, as she whipped up a smile from a large and varied stock. She

said, ‘Tell me—’ enticingly. She sat there on the trunk of the tree by the

rubbish-tip with an effect of abandonment. The world was in her heart already,

like the small spot of decay in a fruit. She was without protection—she had no

grace, no charm to plead for her; his heart was shaken by the conviction of

loss. He said, ‘My dear, be careful …’

‘What of? Why are you

going away?’

He came a little nearer;

he thought—a man may kiss his own daughter, but she started away from him.

‘Don’t you touch me,’ she

screeched at him in her ancient voice and giggled. Every child was born with

some kind of knowledge of love, he thought; they took it with the milk at the

breast; but on parents and friends depended the kind of love they knew—the

saving or the damning kind. Lust too was a kind of love. He saw her fixed in

her life like a fly in amber—Maria’s hand raised to strike: Pedro talking

prematurely in the dusk: and the police beating the forest—violence everywhere.

He prayed silently, ‘O God, give me any kind of death—without contrition, in a

state of sin—only save this child.’

And

here we get more Christian anthropology: “Every child [is] born with some kind

of knowledge of love” but “the world was in her heart already, like the small

spot of decay in a fruit.” [Actually as

I think on it, this is more Catholic anthropology then general Christian. Some Protestant denominations believe in

total depravity of humanity. That doesn’t

fit here. Catholics believe we are born

with the capacity for both.] And so we

see why Brigitta is alluded to as a “young woman” and not a child. She has lost her innocence. Hunger, her mother’s harshness, Pedro’s

worldly diatribes have smudged her soul.

He makes one last effort to speak to her heart. I can’t quote the entire scene, but it’s

worth reading. At one point he falls to

his knees.

He went down on his knees

and pulled her to him, while she giggled and struggled to be free: ‘I love you.

I am your father and I love you. Try to understand that.’ He held her tightly

by the wrist and suddenly she stayed still, looking up at him. He said, ‘I

would give my life, that’s nothing, my soul … my dear, my dear, try to

understand that you are—so important.’ (82)

I

don’t think that giving up your soul for someone, which would be the ultimate

death, is something the Catholic Church would approve (it smacks of making a

deal with the devil) but he does say that several times in the novel. And I think he’s sincere about it too. It’s Greene trying to show he will die for

his love. Right after the priest says he

loves her and she’s so important, we get this coming from the priest’s inner

thoughts:

That was the difference,

he had always known, between his faith and theirs, the political leaders of the

people who cared only for things like the state, the republic: this child was

more important than a whole continent.

And

just like Coral, who separated the politics of a situation from the human

connection, so too the whisky priest separates the politics of Mexico with his

love for her. The philosophic

underpinnings are right out of John’s first epistle, the separation of the

worldly with the love in God, as I quoted above.

Finally

he tries again to reach her heart, manages a kiss, says goodbye, and when he

departs can feel the “whole vile world coming round the child to ruin

her.” We never do hear about Brigitta

again, but one hopes that just as the whisky priest’s heart to heart conversation

and prayers effects Mr. Tench and his life, one hopes they will have a positive

effect on Brigitta too in the future.

.jpg)