Home

"Love follows knowledge."

Monday, August 24, 2020

Matthew Monday: Haircut

Sunday, August 23, 2020

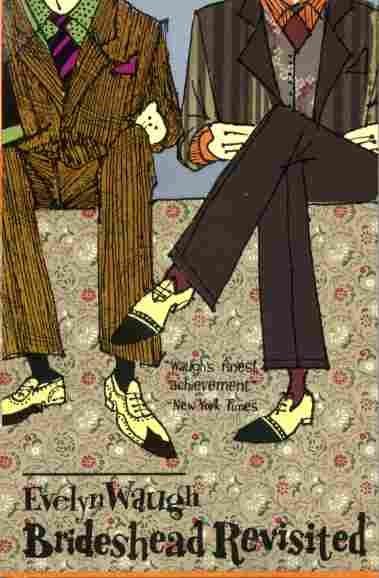

Literature in the News: Brideshead Revisited

Friday, August 21, 2020

Faith Filled Friday: Entering the Gates of the Kingdom

Monday, August 17, 2020

Matthew Monday: By the Beach on the Assumption of Mary

Saturday, August 15th, was the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and there is a tradition of blessing of the ocean and sea on this day. Catholic World Report explains it:

For hundreds of years,

Catholic parishes in coastal cities have participated in the tradition of

blessing the sea and praying for the intercession of the Blessed Virgin Mary on

the Feast of the Assumption.

While believers in

landlocked areas may be unfamiliar with the practice, it is a longstanding

tradition that provides an opportunity not only to pray for safe travel at sea

during the coming year, but also to profess one’s faith outside of church

walls, one priest told CNA.

This

happens to be a traditions some five hundred years old.

The tradition of blessing

of the sea dates back to 15th century Italy and has since become a custom in

coastal cities throughout Europe and the United States.

According to the Trenton

Monitor, the custom is believed to have begun when a bishop traveled by sea

during a storm on the Feast of the Assumption. The bishop then threw his

pastoral ring into the ocean and calmed the waters.

So I decided to take Matthew and we headed to the beach on Staten Island. I snapped a picture from the sand bank—perhaps it’s called a “seawall”—that was built as protection from hurricanes.

Matthew

took his skateboard, which he didn’t use and I wound up carrying. But we had a nice couple of hours, and I gave

the ocean a blessing. ;)

Saturday, August 15, 2020

Lord of the World by Robert Hugh Benson, Part 5

This is the fifth and final post on Robert Hugh Benson’s novel, Lord of the World.

You

can find Part 1 here.

Part

2 here.

Part

3 here.

Part 4 here.

Book

3, Chapter V

Oliver

has been searching for his wife ever since she left and now fears she has

become a Catholic or is in the process of euthanasia. He is interrupted by a phone call that the

government has discovered there is a new pope and Felsenburgh has come and

called for a council in which Oliver needs to attend. At the council Oliver hears from Felsenburgh’s

secretary what has come about.

Intelligence has learned through the betrayal of Cardinal Dolgorovski

that a new Pope has been elected and has been directing the church from

Nazareth, and that a secret meeting of the leading Catholics is being convened

on the coming Sunday. The President

proposes that each nation in the world send volors over to annihilate all the

heads of the Church and so permanently eliminate all possible succession to the

papacy. The bill is passed. On Saturday Oliver boards the English volor and

travels toward Palestine to be part of the bombing mission.

Book

3, Chapter VI

The Catholic hierarchy are gathered and crowded at the house in Nazareth, and it is Pentecost morning. All are gathered except Cardinal Dolgorovski, and his absence is noticed. Cardinal Corkran recounts a series of events that explain that Cardinal Dolgorovski has betrayed them, and so it is evident that the government knows their whereabouts. Pope Silvester says it does not matter. He has had a vision from God of the coming events, and has everyone else prepare for Mass in two hours. An hour later the papal attendant priest walks toward the chapel and notices the country folk rushing to escape. He can feel the stillness of eternity upon him. At the chapel he falls asleep only to wake in the middle of Mass. As Mass concludes, there is a clamor outside. He goes out to look and it is evident now that the volors are coming to destroy them. Returning inside he joins the gathered religious in singing the hymn O salutaris hostia. The gathered take the monstrance with the Blessed Sacrament and process it outside singing the hymn Pange Lingua. And as the volors approach with their impending arsenal the material world dissolves into the end of times.

###

I must have read that section III of the last chapter three or four times. I'm still not sure I got the ending right. Is it Christ who is be referred to as the personal pronoun in the repeated "He was coming"? Or is it Felsenburgh? If it is Christ, then my reading above is correct and it's the apocalypse on which the novel ends, and the victory is the victory of Christ. If it is Felsenburgh that is coming, then the novel ends with the destruction of the church and victory for the atheists.

I assume the victory is with Christ, or the novel wouldn't make sense. But it is ambiguous, is it not? Is it me?

###

I

have to admit I spent three hours trying to translate all the Latin in that

section III. Finally I realized they

were parts of well-known hymns. Here you

can read about and get the translation of Osalutaris hostia. And here you can read about and get the

translation of Pange lingua gloriosicorporis mysterium. My translation was close in some cases but stilted in others. I wound up taking each part of the Latin

lyric and providing the English translation.

Let me give this to you. It may

help in your reading.

Latin translations of those spoken in Book 3, Chapter VI, Section III

(1) p. 333 [from “O Salutaris Hostia”]

O Salutaris Hostia // Qui coeli pandis ostium. . .

O

Saving Victim // He opens the door of heaven

(2)

p. 333 [from “O Salutaris Hostia”]

... Uni Trinoque Domino ....

To

the One and Triune Lord.

(3)

p 334 [from “O Salutaris Hostia”]

.. Qui vitam sine termino // Nobis donet in patria ...._

He

who life without end // Brings us to our home

(4)

p. 334

Pange Lingua

Sing

Tongue

(5)

p. 334 [from Pange Lingua]

.. In suprema nocte coena,_

On

the night of the last supper

(6)

p. 335 [from Pange Lingua]

Recumbens cum fratribus

Observata lège plena

Cibis in legalibus

Cibum turbae duodenae

Se dat suis manibus ....

Reclining

with His brethren,

once

the Law had been fully observed

with

the prescribed foods,

as

food to the gathered Twelve

He

gives Himself with His hands.

(7)

p. 335 [from Pange Lingua]

Verbum caro, panem verum // Verbo carnem efficit

In

the Word was the true bread // the Word made flesh

(8)

p335 [from Pange Lingua]

Et si census deficit // Ad formandum cor sincerum // Sola fides sufficit ....

And

if sense is deficient // to form a sincere heart // Faith alone is enough…

(9)

p. 336 [from Pange Lingua]

TANTUM ERGO SACRAMENTUM

VENEREMUR CERNUI

ET ANTIQUUM DOCUMENTUM

NOVA CEDAT RITUI.

Therefore,

the great Sacrament

let

us reverence, prostrate:

and

let the old Covenant

give

way to a new rite.

(10)

p. 336 [from Pange Lingua]

PRAESTET FIDES SUPPLEMENTUM

SENSUUM DEFECTUI ....

May

faith supplement

the

defects of our senses ....

(11)

p. 337 [from Pange Lingua]

.... GENITORI GENITOQUE

LAUS ET JUBILATIO

SALUS HONOR VIRTUS QUOQUE

SIT ET BENEDICTIO

PROCEDENTI AB UTROQUE

COMPAR SIT LAUDATIO.

To

the Begetter and the Begotten

be

praise and jubilation,

greeting,

honour, strength also

and

blessing.

To

the One who proceeds from Both

be

equal praise

(12)

.337 [from Pange Lingua]

PROCEDENTI AB UTROQUE

COMPAR SIT LAUDATIO…

To

the One who proceeds from Both

be

equal praise

###

My

Reply to Irene and Kerstin who mentioned that “Sister” has

a tradition of a title for nurse in England and Germany:

To Irene and Kerstin on

Nursing, I didn't know that. So I now have done some research. It seems the

title "sister" for nurse came about from the middle ages on. Nurses

in hospitals were invariable religious sisters. Actually it may go back all the

way to apostolic times. Phoebe, who is identified as a "deaconess" in

Acts appears to have cared for the sick as part of her responsibilities. The

term apparently stuck in Britain, and I find Benson's use of it to be totally

intentional on his part, carrying the irony that I pointed out earlier.

My

Reply to Joseph on why this dystopian novel doesn’t have

the attention of other great dystopian novels:

Yes. Perhaps more than

just the ending. The religious subject matter itself probably precludes a good

number of people to not care about it. And then there are the Protestants who

recoil from anything Catholic. And then this attacks the secularists

themselves, so they would never buy into it. It's a novel that should be read.

I am going to give it five stars. Except for some minor criticism I pointed out

earlier, this novel should be a classic.

Kerstin

Comment:

Oh my gosh, Manny, this [translation

of Latin] was a herculean endeavor. I was a little disappointed my text didn't

offer the translations. Thank you!

I thought that the novel

ended with Mass and adoration was perfect.

My

Reply to Kerstin:

LOL. it was getting to be

Hurculean. It reminded me of my college days taking Spanish and needing to

translate a passage into English. I was never very good with foreign languages.

Yes, I loved the novel

ending with a Mass and process of the Blessed Sacrament chanting hymns. What a

great movie scene that would make!!

My only criticism of the

ending is that it doesn't seem definitely clear as to what happened. Was it

Christ that was coming with the apocalypse? Or was it Felsenburgh with the

destruction of the church? How do you all read that ending.

Joseph

Reply, agreeing with others that they see the ending as

Christ coming:

It also makes Mabel's

death more ambiguous, it's hard to tell if she dies before Christ's return or

if he comes back in time for her to repent fully which I thought was a really

nice touch.

My

Reply to Joseph:

Hmm, that's interesting.

Now that you mention it, Benson is very particular of the days of the week of

those last chapters. Let me see if I can construct a timeline.

###

My

Reply to Gerri who questioned the ending:

Hi Gerri. Let's see if can address some of your

questions.

"I didn't like the

ending as much as I liked the rest of the book. It was overwritten in my estimation

and that took away from my reading enjoyment."

In what way was it

overwritten? I thought ending with the

Mass and then followed by the religious in procession with the Blessed

Sacrament while chanting hymns was brilliant.

I could easily see that as a movie scene. My complaint with the ending was that it left

an ambiguity as to whether the Church was destroyed by the volors or Christ

comes with the end of times in an apocalypse.

I think by and large, the ending is supposed to be the latter, the end

of times. It’s the only way to interpret

the last sentence of the novel: “Then this world passed, and the glory of

it.”

I don’t know why Benson

did not make it clear. Perhaps he

thought it was clear. Like a good

symphony, a novel should end with a closed cadence. Beethoven is never hesitant to nail shut a

symphony. No ambiguity with him. ;)

“Another thing I

questioned is why Benson didn't wrap up the thread about Oliver.”

That’s another reason to

consider the end of times ending to the novel.

All earthly life would be over, and Oliver will face his judgement along

side Felsenburgh.

“Did I miss it or did

anybody continue earlier discussions about the physical similarity between Fr.

Fleming/Pope Silvester and Felsenburgh? Christ/Anti-Christ as the final battle

might indicate?”

No you did not miss

that. It was never brought back up. I was going to ask people’s opinions on

that. We can do that now. I came to the conclusion it was a

Christ/Anti-Christ parallel too. I don’t

feel I know enough about the Book of Daniel and Revelation to have an educated

thought on that.

###

My Goodreads Review:

A more precise rating is four and a half stars since it is not a perfect work, but I erred on the higher side because I thought this a beautifully written and prophetic novel of ideas. As you can read from its description, it’s a dystopian novel of a future where secular humanism has come to dominate the world and seeks the final eradication of religion, especially Christianity. The one religion that remains is Roman Catholicism, but any Christian denomination would have sufficed. The author is a Roman Catholic priest, so he is writing from what he knows. The novel was written in 1907 and is set a hundred years into its future, which would make it now. In that future, secular humanism has come to dominate society and seeks the eradication of all religion, especially Christianity since it proposes a metaphysical world of a transcendent God who’s values go beyond the human ego. The totalitarianism of Orwell has come and gone, but the secular stranglehold of Benson’s dystopian vision is very much with us. And what does Benson see as the source of the secularist’s power? Humanitarianism, as seen through the ego and not of Christ, and cold logic at the expense of human values. The Lord of the world has been replaced by a lord over human beings, all of which will bring the narrative to an apocalyptic ending.

Not

only is this a novel of ideas but one of extraordinary lyricism. Robert Hugh Benson is a gifted writer. There are scenes delineated in the best

tradition of fine Victorian prose. Here

is an example of a moment when Fr. Percy Franklin, the novel’s central figure,

enters a chapel to pray.

It was drawing on towards

sunset, and the huge dark place was lighted here and there by patches of ruddy

London light that lay on the gorgeous marble and gildings finished at last by a

wealthy convert. In front of him rose up the choir, with a line of white

surpliced and furred canons on either side, and the vast baldachino in the

midst, beneath which burned the six lights as they had burned day by day for

more than a century; behind that again lay the high line of the apse-choir with

the dim, window-pierced vault above where Christ reigned in majesty. He let his

eyes wander round for a few moments before beginning his deliberate prayer,

drinking in the glory of the place, listening to the thunderous chorus, the

peal of the organ, and the thin mellow voice of the priest. There on the left

shone the refracted glow of the lamps that burned before the Lord in the

Sacrament, on the right a dozen candles winked here and there at the foot of

the gaunt images, high overhead hung the gigantic cross with that lean,

emaciated Poor Man Who called all who looked on Him to the embraces of a God.

Such

a simple moment, and yet Benson makes it come alive. And here also is the dramatic entrance into

the novel of its chief antithesis, the newly elected secular President of the

world, dubbed Lord of the World, Julian Felsenburgh. Here he enters on some sort of hovering craft

over a cheering crowd.

High on the central deck

there stood a chair, draped, too, in white, with some insignia visible above

its back; and in the chair sat the figure of a man, motionless and lonely. He

made no sign as he came; his dark dress showed vividedly against the whiteness;

his head was raised, and he turned it gently now and again from side to side.

It came nearer still, in

the profound stillness; the head turned, and for an instant the face was plainly

visible in the soft, radiant light.

It was a pale face,

strongly marked, as of a young man, with arched, black eyebrows, thin lips, and

white hair.

Then the face turned once

more, the steersman shifted his head, and the beautiful shape, wheeling a little,

passed the corner, and moved up towards the palace.

There was an hysterical

yelp somewhere, a cry, and again the tempestuous groan broke out.

There

are many such startling scenes that this novel would make a superb movie. Why hasn’t this been made into a movie? The final climatic scene where the religious

have just finished Mass and are in procession with the Blessed Sacrament

chanting Latin hymns while the onslaught of the destroying bombers make their

way is brilliant. This is a novel that

should have a much wider audience, and should be required reading across

universities if universities had the incentive to be balanced. But they are not. So it behooves you to read the novel for

yourself.

Wednesday, August 12, 2020

Lord of the World by Robert Hugh Benson, Part 4

This is the fourth post on Robert Hugh Benson’s novel, Lord of the World.

You

can find Part 1 here.

Part

2 here.

Part

3 here.

Book

3, Chapter III

Oliver

has noticed that the destruction of the Catholic world has disturbed Mabel

psychologically and emotionally. She

feels the government has betrayed the humanitarian ideals on which they were to

bring about. Oliver goes over the

rationale for how the only way to bring about this ideal was to destroy those

that disagreed with it. Oliver is

informed that Felsenburgh has passed a bill that would exterminate all

Catholics from the earth. Oliver tries

to explain the reason for the new bill but Mabel cannot accept it. She secretly leaves the house. Late that night Mabel has made an unplanned

visit to Mr. Francis to ask him, an ex-priest, why Catholics believe in

God. He explains the fundamentals and

declares it is based on emotion.

Book

3, Chapter IV

A

week later Mabel wakes up to a home where she has come to put an end of

it. She has waited the legally required

eight days to ensure certainty, and thinking over the failure of the

Humanitarian Faith and the new persecution laws, despite seeming perfectly

logical, has caused her to lose faith in life itself and seek euthanasia. On this her last day, she continues to be

certain it is the right course of action.

A little while later she reads over her last letter to Oliver explaining

why she has made this decision. Then the

nurse comes in with the euthanasia machine, but Mabel is looking out the window

and frightened at the black sky. The

nurse reassures her and shows her how to use the machine. Alone with the machine, she looks again out

the window at the black sky. She speaks

to God, as if He existed, and was sorry for it all. She then fumbles with the mask and turns the

handle where a sweet gas strikes her. As

her earthly moments end, she sees the beyond.

###

I

have to say I was quite moved with chapter four of the third book. I’d like to highlight some details. First let’s look at her decision to end her

life. Here early on she describes her

emotions as she came to this “home.”

She had suffered, of

course, to some degree from reactions. The second night after her arrival had

been terrible, when, as she lay in bed in the hot darkness, her whole sentient

life had protested and struggled against the fate her will ordained. It had

demanded the familiar things the promise of food and breath and human

intercourse; it had writhed in horror against the blind dark towards which it

moved so inevitably; and, in the agony had been pacified only by the

half-hinted promise of some deeper voice suggesting that death was not the end. (p. 290-291)

The

word that sticks out is “will,” “the fate her will ordained.” The word comes up especially at the end when

she has set the euthanasia machine in motion.

“Then the steady will that had borne her so far asserted itself, and she

laid her hands softly in her lap, breathing deeply and easily” (303). “Then she understood that the will had

already lost touch with the body…” (303).

Ending her life is an act of will, something that has to override (1)

her survival instinct, which Benson might argue was planted in each of us from

God as natural biology, and (2) has to override her heart which Benson might

argue is linked to God in natural morality.

Overriding the will is theologically choosing to do evil, to contradict

God’s natural course.

Also I think the will is linked to logic and all the arguments Oliver makes and Mabel accepts pertaining to logic. Notice how often logic is employed. Something is logical only if people agree on the ground rules of which the facts are based. Something that is logical to a European can be completely illogical to a native of an Amazonian jungle. Just because something seems logical doesn’t mean it is true. Once you have accepted the logic, one carries out that action from an exertion of the will. This is especially true when the logic violates natural instinct and God’s morality as I mentioned above.

###

I

am also fascinated by what Mabel sees in the sky and then as she dies

physically and transition to the metaphysical.

Here is the scene when Sister Anne comes in the machine to find Mabel

staring out the window at the sky.

When Sister Anne came in

a few minutes later, she was astonished at what she saw. The girl crouched at

the window, her hands on the sill, staring out at the sky in an attitude of

unmistakable horror.

Sister Anne came across

the room quickly, setting down something on the table as she passed. She

touched the girl on the shoulder.

“My dear, what is it?”

There was a long sobbing

breath, and Mabel turned, rising as she turned, and clutched the nurse with one

shaking hand, pointing out with the other.

“There!” she said. “There

look!”

“Well, my dear, what is

it? I see nothing. It is a little dark!”

“Dark!” said the other.

“You call that dark! Why, why, it is black—black!” (p. 297)

First, before I get to the sky, why is the nurse’s title “sister”? She is a “sister” of this new humanitarian religion. In Benson’s day, many hospitals across Europe were worked by religious sisters. It’s quite ironic that Sister Anne is the new Sister of Mercy.

As

to what they see, there is a decided disconnect. So who is seeing the reality? Here’s how Benson portrays the disconnect.

“Nurse,” she said more

quietly, “please look again and tell me if you see nothing. If you say there is

nothing I will believe that I am going mad. No; you must not touch the blind.”

No; there was nothing.

The sky was a little dark, as if a blight were coming on; but there was hardly

more than a veil of cloud, and the light was scarcely more than tinged with

gloom. It was just such a sky as precedes a spring thunderstorm. She said so,

clearly and firmly. (297-298)

Is Benson describing the sky objectively in that paragraph or is that description filtered through the point of view of Sister Anne? That is an important decision the reader has to make there. If Benson is objectively describing the sky, then Mabel is experience some sort of delusion from her nerves. But if it is the sky seen through Sister Anne’s point of view, then there is some supernatural event going on that only Mabel is allowed to see. I believe it is the second. Mabel is being given a grace from above as a call to not go through it.

###

I

was very moved by her last confession, though she didn’t think of it as a

confession.

Then, hardly knowing what

she said, looking steadily upon that appalling sky, she began to speak....

“O God!” she said. “If

You are really there really there ”

Her voice faltered, and

she gripped the sill to steady herself. She wondered vaguely why she spoke so;

it was neither intellect nor emotion that inspired her. Yet she continued....

(p. 302)

Her

will subsides here. This comes out of

her without her even thinking about it.

I think it’s an act of grace, God leading her to either away from what

she wants to do or at least an act of penance.

She continues.

“O God, I know You are

not there of course You are not. But if You were there, I know what I would say

to You. I would tell You how puzzled and tired I am. No No I need not tell You:

You would know it. But I would say that I was very sorry for all this. Oh! You

would know that too. I need not say anything at all. O God! I don’t know what I

want to say. I would like You to look after Oliver, of course, and all Your poor

Christians. Oh! they will have such a hard time.... God. God You would

understand, wouldn’t You?” ...

She

even makes amends to the Christians, and cares about their difficulties to come. This is so tender that as a reader I so

wished she would pull back from the act.

But alas she doesn’t, and even asks God if He understands. And God I think responds.

Again came the heavy

rumble and the solemn bass of a myriad voices; it seemed a shade nearer, she

thought.... She never liked thunderstorms or shouting crowds. They always gave

her a headache ...

Of course He doesn’t approve. Will this

confession be her saving grace?

Perhaps. Perhaps there is a

suggestion in her final moments.

###

Those

last moments of Mabel passing may be one of the best descriptions of a person

dying that I have ever read. Mabel was

curious as to what she would feel, and she “would at least miss nothing of this

unique last experience.” So we get her

observations in detail. Her eyes are

looking at that sky once again.

It seemed at first that there was no change.

There was the feathery head of the elm, the lead roof opposite, and the

terrible sky above. She noticed a pigeon, white against the blackness, soar and

swoop again out of sight in an instant....

(p. 303)

Ah,

a white pigeon, the Holy Spirit. But

then she began to lose her will.

There was a sudden

sensation of ecstatic lightness in all her limbs; she attempted to lift a hand,

and was aware that it was impossible; it was no longer hers. She attempted to

lower her eyes from that broad strip of violet sky, and perceived that that too

was impossible. Then she understood that the will had already lost touch with

the body, that the crumbling world had receded to an infinite distance that was

as she had expected, but what continued to puzzle her was that her mind was

still active.

What

Benson does so beautifully here is have the beginnings of a dissociation

between the body and soul. And the

paragraph continues as the soul and body start to pull apart.

It was true that the world

she had known had withdrawn itself from the dominion of consciousness, as her

body had done, except, that was, in the sense of hearing, which was still

strangely alert; yet there was still enough memory to be aware that there was

such a world that there were other persons in existence; that men went about

their business, knowing nothing of what had happened; but faces, names, places

had all alike gone. In fact, she was conscious of herself in such a manner as

she had never been before; it seemed as if she had penetrated at last into some

recess of her being into which hitherto she had only looked as through clouded

glass. This was very strange, and yet it was familiar, too; she had arrived, it

seemed, at a centre, round the circumference of which she had been circling all

her life; and it was more than a mere point: it was a distinct space, walled

and enclosed.... At the same instant she knew that hearing, too, was gone.... (p. 304)

What

has happened I think is that all physical sensation is now gone except for

sight, and I might venture to say that her physical sight is gone but there is

now some sort of metaphysical sight. The

experience continues.

The enclosure melted,

with a sound of breaking, and a limitless space was about her limitless,

different to everything else, and alive, and astir. It was alive, as a

breathing, panting body is alive self-evident and overpowering it was one, yet

it was many; it was immaterial, yet absolutely real real in a sense in which

she never dreamed of reality....

What

she saw in her metaphysical sight suddenly shatters. She has broken through into a new a new world

and a new life, and she is aware of it.

Yet even this was

familiar, as a place often visited in dreams is familiar; and then, without

warning, something resembling sound or light, something which she knew in an

instant to be unique, tore across it....

Then she saw, and

understood....

What did she see? What does she now understand? One can guess: Christ? Heaven? Angels? It is the mystery that we all await, and Benson quite properly leaves it a mystery.

The

breaking light from the darkness in the sky reminded me of the verse in the

Canticle of Zachariah, of which is prayed in every Lauds of the Divine Office:

In the tender compassion

of our God

the dawn from on high

shall break upon us,

to shine on those who

dwell in darkness and the shadow of death,

and to guide our feet

into the way of peace. (Luke 1: 78-79)

There

is a sort of tender compassion in her death, despite her violation of God’s law

against suicide. She’s only a character

in a novel, and Benson has no obligation to explain further, but one hopes she

is saved and not damned.

Frances

Comment:

I'd like to share what

Joseph Pearce writes in his excellent book Literature:

What Every Catholic Should Know, and hope this is a good time to do it:

"Lord of the World deserves to stand

beside Brave New World and 1984 as a classic of dystopian fiction.

In fact, though Huxley's and Orwell's modern masterpieces may merit equal

praise as works of literature, they are patently inferior as works of prophecy.

The political dictatorships that gave Orwell's novel an ominous potency have

had their day. Today, his cautionary fable serves merely as a timely reminder

of what has been and what may be again if the warnings of history are not

heeded. Benson's novel, on the other hand, is coming true before our eyes.

"The world depicted

in Lord of the World is one where creeping

secularism and godless humanism have triumphed over religion and traditional

morality. It is a world where philosophical relativism has triumphed over

objectivity and where, in the name of tolerance, religious doctrine is not

tolerated. It is a world where euthanasia is practiced widely and religion

hardly practiced at all. The lord of this nightmare world is a benign-looking

politician intent on power in the name of 'peace,' and intent on the

destruction of religion in the name of 'truth.' In such a world, only a small

and defiant Church stands resolutely against the demonic 'Lord of the World.'

"We can hope that in

healthier times, Benson, so long neglected, will once more be seen among the

stars of the literary firmament, his own star once more in the ascendant."

(pages 148-149)

My Reply to Frances:

Well, one could quibble

that Orvell's "ominous potency" still lives in China. But on the

whole that is so true. Benson is much more relevant to our times. It is very

prophetic!

Susan Comment:

That is fascinating that

you expressed your comment like that Manny...

That reminds me of the

book I am reading right now, "America on Trial, A Defense of the

Founding"... It really stresses the ideas of the primacy of the intellect

vs. the primacy of the will.... and what happens when they get flipped...

The Aristotelian-Thomistic

idea of Logos, and God's will being led by HIs Intellect, Natural Law...; the

medieval roots of constitutionalism vs. the development of nominalism (no

natures, so no natural law) and voluntarism, William of Ockham and Martin

Luther, severing Aquinas' synthesis of reason and faith, primacy of the

will/God is capricious... -> political absolutism. It is an excellent

book... anyway, I think your comments on logic (reason) and will have a much

more profound and integral connection to The Lord of the World than you might

have thought, a connection to the uniqueness of America and the enshrinement of

Natural Law/primacy of reason (in theory anyway, always imperfectly actualized)

vs. the looming (ever closer!) triumph of primacy of will (totalitarianism)....

a perfect read for July 4th! Have a wonderful, safe, holiday weekend!

My Reply to Susan:

Good comment Susan.

Another way to phrase this is that Mabel supersedes God's will with her's. It

becomes my will, not Thy will. Where have we seen that before? It seems to come

up regularly in Catholic fiction. I admit, it's sometimes hard to discern God's

will but I am certain that taking one's life is in opposition to God's will.

Actually I have been

tracking the motifs of logic and will throughout the novel. It's not just in

this chapter, but it seems to come to a climax here.