This

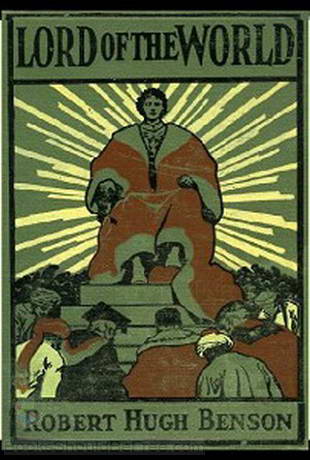

is the second post on Robert Hugh Benson’s novel, Lord of the World.

You

can find Part 1 here.

Book1,

Chapter IV

A

mysterious man who says he is in the employment of Oliver Brand shows up at Fr.

Percy's residence to request a secret meeting with Oliver's mother who wishes

to return to the church. Fr. Percy agrees

to meet the old woman at 10 PM when Oliver and Mabel are away. On the way to the Brand house that evening,

the rain Fr. Percy is riding comes to a halt and a large crowd starts cheering. They are cheering a news flash that has come

across the station that the diplomatic meeting has ended, peace has been

announced, and that "Universal Brotherhood Established." Finally he meets with Mrs. Brand, welcomes

her back into the church with the sacrament of reconciliation, and promises to

bring her Holy Communion at next opportunity.

She tells him of a frightful dream involving Felsenburgh. As she concludes, she hears her son and Mabel

enter the house.

Book

1, Chapter V

Oliver

and Mabel find Fr. Percy with Mrs. Brand.

They ask him to step into the next room to discuss this. Oliver is emotionally upset by finding a

priest in his house, but Mabel takes control of the situation by having Percy

explain what has happened and extracting a promise from him to not make Mrs. Brand's

return to the church public knowledge.

Mabel tells him how London is up in joy because "peace" has

been established in the world. On his

return train ride home, the Londoners are in a delirious frenzy. Finally he steps off the train in the wee

hours of the morning where it is still dark but the atmosphere lit in other

worldly light. People are bunched in a

crowd in anticipation. Percy struggles

to find an advantage point to see what all are waiting to see. As the dawn breaks overhead, he sees up above

floating in some sort of flying platform a young man who we presume to be

Felsenburgh sitting in a throne-like chair.

###

Section

II of chapter V is another breathtakingly beautifully written sub-chapter. Read this chapter a second time to take it

all in. My goodness, Benson is such a

good writer. Let me just quote a couple

of sections. First when he comes out of

the station and onto the street.

There, too, was an

astonishing sight. The lamps still burned overhead, but beyond them lay the

first pale streaks of the false dawn. The street that ran now straight to the

old royal palace, uniting there, as at the centre of a web, with those that

came from Westminster, the Mall and Hyde Park, was one solid pavement of heads.

On this side and that rose up the hotels and "Houses of Joy," the

windows all ablaze with light, solemn and triumphant as if to welcome a king;

while far ahead against the sky stood the monstrous palace outlined in fire,

and alight from within like all other houses within view. The noise was

bewildering. It was impossible to distinguish one sound from another. Voices,

horns, drums, the tramp of a thousand footsteps on the rubber pavements, the

sombre roll of wheels from the station behind--all united in one overwhelmingly

solemn booming, overscored by shriller notes.

It was impossible to

move.

And

then the crowd becomes one strange body, acting with one will.

Gradually he became aware

that this crowd was as no other that he had ever seen. To his psychical sense

it seemed to him that it possessed a unity unlike any other. There was

magnetism in the air. There was a sensation as if a creative act were in

process, whereby thousands of individual cells were being welded more and more

perfectly every instant into one huge sentient being with one will, one

emotion, and one head. The crying of voices seemed significant only as the

stirrings of this creative power which so expressed itself. Here rested this

giant humanity, stretching to his sight in living limbs so far as he could see

on every side, waiting, waiting for some consummation--stretching, too, as his

tired brain began to guess, down every thoroughfare of the vast city.

He did not even ask

himself for what they waited. He knew, yet he did not know. He knew it was for

a revelation--for something that should crown their aspirations, and fix them

so for ever.

And

finally the climatic vision of Felsenburgh as a god-like king.

High on the central deck

there stood a chair, draped, too, in white, with some insignia visible above

its back; and in the chair sat the figure of a man, motionless and lonely. He

made no sign as he came; his dark dress showed vividedly against the whiteness;

his head was raised, and he turned it gently now and again from side to side.

It came nearer still, in

the profound stillness; the head turned, and for an instant the face was

plainly visible in the soft, radiant light.

It was a pale face,

strongly marked, as of a young man, with arched, black eyebrows, thin lips, and

white hair.

Then the face turned once

more, the steersman shifted his head, and the beautiful shape, wheeling a

little, passed the corner, and moved up towards the palace.

There was an hysterical

yelp somewhere, a cry, and again the tempestuous groan broke out.

This

is just superb writing.

###

At

the end of that scene in Book 1, Chapter V, there is a strange detail. I wonder if others picked up on it. Felsenburgh is described as having “a pale

face, strongly marked, as of a young man, with arched, black eyebrows, thin

lips, and white hair.” White hair for a

young man? Percy too is described as

having white hair. From the Prologue:

Father Percy Franklin,

the elder of the two priests, was rather a remarkable-looking man, not more

than thirty-five years old, but with hair that was white throughout; his grey

eyes, under black eyebrows, were peculiarly bright and almost passionate; but

his prominent nose and chin and the extreme decisiveness of his mouth reassured

the observer as to his will. Strangers usually looked twice at him. (p. xvi)

Both

young, both with unusually white hair for their age, and both striking in

appearance. I don’t know the

significance, but there has to be something.

Hopefully Benson will clarify.

Irene

Commented:

Felsenburgh's appearance,

descending from above, white haired, made me think of the "Son of

Man" figure in Daniel.

My

Reply:

Hmm, it made me think of

Ezekiel, which is very similar to Daniel. From Ezekiel, chapter 10:

1 Then I looked and there

above the firmament over the heads of the cherubim was something like a

sapphire, something that looked like a throne. 2 And he said to the man dressed

in linen: Go within the wheelwork under the cherubim; fill both your hands with

burning coals from the place among the cherubim, then scatter them over the

city. As I watched, he entered. 3 Now the cherubim were standing to the south

of the temple when the man went in and a cloud filled the inner court. 4 The

glory of the LORD had moved off the cherubim to the threshold of the temple;

the temple was filled with the cloud, the whole court brilliant with the glory

of the LORD. 5 The sound of the wings of the cherubim could be heard as far as

the outer court; it was like the voice of God Almighty speaking.

The image is definitely

Old Testament Biblical.

Irene

Replied:

Manny, here is the text

that I thought of.

Daniel 7:9-14

As I watched, thrones

were set up and the Anointed One took his throne. His clothing was snow white

and the hair on his head was white as wool....

As the visions during the

night continued, I saw one like a son of man coming on the clouds of heaven....

He received dominion,

glory and kingship, nations and peoples of every language.`

My

Reply:

This is spot on Irene!

Yes, this is directly what Benson is alluding to. There is no question about

it.

###

Now

that we’ve completed the first part, it’s a good place to take stock of where

we are. We can see that Benson is

running two plots in parallel. One is a

grand, overarching narrative where global, and even cosmic and spiritual,

forces are in conflict. The other is an

individualized, more local plot pertaining to the various issues in the

character’s lives. Of course there is a

thematic relationship between the two plots.

This approach is not unusual for novels dealing with expansive and

global stories.

The

main global force presented is the conflict between the communist, and mostly

atheist, West against the empire from the east which has an alliance of eastern

religions. Much has been made of the

West’s lack of religion, albeit with a small contingent of Catholicism, but

Benson really has not elaborated in any way the East’s religious

conglomeration. The other force that is

prominent is the internal spiritual conflict that is going on metaphysically

inside the West. Freemasonry, which I

take is an agnostic religion-like philosophy, pure atheistic communism, and the

struggling Roman Catholicism are in some way competing for the metaphysical

soul of the world, or at least the West.

I identified the East/West conflict the main global force,

but at the end of Part 1, that conflict is actually resolved. So is this really the main conflict in the

novel? What remains is a spiritual

conflict between the three belief systems.

As

to the individual issues of the various characters, we see defections from

Catholicism, we see an old woman return to her faith, we see in Oliver Brand an

atheist who is actually lost in that he doesn’t know what to make of

Catholicism nor Freemasonry, and we see Percy valiant as the alluded knight of

his name, trying to do God’s will through his support of Catholicism. Perhaps the second most important character

in the entire novel, Felsenburgh, has been shrouded in mystery, has made his

very first appearance at the end of Part 1 as a triumphant hero, and hasn’t

even spoken a word yet. How does

Felsenburgh’s entrance into the plot now effect the various characters? One waits to see.

Fascinating. I have avoided reading how this turns

out. I really can’t tell where this is

going. But I’m hooked.

###

Book

2, Chapter I

The

day after the diplomatic resolution and Felsenburgh appearing in London like a

deity floating down from heaven, Oliver sits reading the evening paper

summarizing the historic events. We

learn of Felsenburgh being received as a Christ, though a completely secular

one, and that the editors anticipate the world has now entered a new age, one

of "Universal Brotherhood," with a new spirit that will replace the

failures of religion. Oliver and Mabel

go on to discuss the significance of the events and take joy in this new

situation. Mabel tries to explain it to

Mrs. Brand, whose illness is getting worse.

Mrs. Brand refuses to accept the new state as good news and just

clutches her rosary as she calls out for the priest. When Oliver returns home the next evening,

Mrs. Brand has died, and Mabel explains she had to euthanize the old woman because

she had gotten worse. Oliver tells Mabel

the news of the day, which is that every country in Europe has offered

Felsenburgh some sort of dictator role in their country but he has refused them

all.

Book

2, Chapter 2

Percy

is summoned to Rome to give council to the Holy Father himself on the state of

the world and the faith. He journeys by

volor from London, across France, over the alps, and into Italy. As he travels, his mind cogitates on how the

world has lost its reliance on God as the transcendent source of all existence

and goodness. As Percy settles in his

Roman quarters at the Vatican he realizes just how Rome has remained a place of

the past, a world where modern conveniences have been left behind. Cardinal Martin meets him at his room to

inform that the Pope wants to see him later that morning. In the interim Percy recalls the nature of

this papacy, that Papa Angelicus has cared nothing about the opinion of the

world and has maintained policies that emphasized human virtue over human

progress. Finally Percy meets the Holy

Father and in his discourse with the Pope, Percy explains the state of the

world, how the world has aligned into two camps, those that believe in God and

those that do not. He foresees that

persecution is coming and what is needed is a new religious order to combat

this heresy. The Pope, satisfied, then

excuses him.

###

My

Comment:

I couldn't believe that

Mabel euthanized Mrs. Brand. I think I had to read that passage four times and

then independently verify it.

My

Comment:

While reading about that

"Universal Brotherhood" I kept thinking of that John Lennon song,

"Imagine". Here are the lyrics:

Imagine

there's no heaven

It's

easy if you try

No

hell below us

Above

us only sky

Imagine

all the people

Living

for today... Aha-ah...

Imagine

there's no countries

It

isn't hard to do

Nothing

to kill or die for

And

no religion, too

Imagine

all the people

Living

life in peace... You...

You

may say I'm a dreamer

But

I'm not the only one

I

hope someday you'll join us

And

the world will be as one

Imagine

no possessions

I

wonder if you can

No

need for greed or hunger

A

brotherhood of man

Imagine

all the people

Sharing

all the world... You...

You

may say I'm a dreamer

But

I'm not the only one

I

hope someday you'll join us

And

the world will live as one

I have come to detest

that song. It's actually amazing how close to the philosophy within the novel

is similar to that. I doubt Lennon had even heard of Lord of the World, but you

can see this impulse really is in our culture and attempting to destroy

Christianity. Pray against it.

###

Chapter

2 of Part 2 might be the intellectual core of the novel. Here we finally see what the progressive,

modern world is contrasted against: a simple, anachronistic world. I love the description of Rome.

It was an extraordinary

city, said antiquarians the one living example of the old days. Here were to be

seen the ancient inconveniences, the insanitary horrors, the incarnation of a

world given over to dreaming. The old Church pomp was back, too; the cardinals

drove again in gilt coaches; the Pope rode on his white mule; the Blessed

Sacrament went through the ill-smelling streets with the sound of bells and the

light of lanterns. A brilliant description of it had interested the civilised

world immensely for about forty-eight hours; the appalling retrogression was

still used occasionally as the text for violent denunciations by the poorly

educated; the well-educated had ceased to do anything but take for granted that

superstition and progress were irreconcilable enemies.

Yet Percy, even in the

glimpses he had had in the streets, as he drove from the volor station outside

the People’s Gate, of the old peasant dresses, the blue and red-fringed wine

carts, the cabbage-strewn gutters, the wet clothes flapping on strings, the

mules and horses strange though these were, he had found them a refreshment. It

had seemed to remind him that man was human, and not divine as the rest of the

world proclaimed human, and therefore careless and individualistic; human, and

therefore occupied with interests other than those of speed, cleanliness, and

precision.

And

then further down:

Already the burden was

lighter, and he was astonished at the swiftness with which it had become so.

Life looked simpler here; the interior world was taken more for granted; it was

not even a matter of debate. There it was, imperious and objective, and through

it glimmered to the eyes of the soul the old Figures that had become shrouded

behind the rush of worldly circumstance. The very shadow of God appeared to

rest here; it was no longer impossible to realise that the saints watched and

interceded, that Mary sat on her throne, that the white disc on the altar was

Jesus Christ. Percy was not yet at peace after all, he had been but an hour in

Rome; and air, charged with never so much grace, could scarcely do more than it

had done. But he felt more at ease, less desperately anxious, more childlike,

more content to rest on the authority that claimed without explanation, and

asserted that the world, as a matter of fact, proved by evidences without and

within, was made this way and not that, for this purpose and not the other. Yet

he had used the conveniences which he hated; he had left London a bare twelve

hours before, and now here he sat in a place which was either a stagnant

backwater of life, or else the very mid-current of it; he was not yet sure which.

That’s

the kind of world I want to live in!

That’s the kind of place I try to make Catholic Thought book club to

be. Of course that’s impossible.

My

Replies to Irene on Rome being described as pre-modern:

#1

Irene, OK, but you

confused me a little. When you say you in your first sentence "had the

opposite reaction" you don't mean you had a different reading of Benson's

writing. You mean you disagree with Benson. Anyone, correct me if I'm wrong but

I think Benson's sympathies are fairly clear here. He's drawing a contrast

between the old world and the modern world, and his sympathies lies with the

old. And while he creates a place where the modern world has not altered, he's

really talking about people's relationship with God. He's writing in 1907, so

while there are some modern conveniences, the real impact of electricity and

the motor engine or even modern medicine hasn't really developed. I don't know

if Benson is saying that technology and science itself is responsible for the

modern world, just that there seems to be a correlation. He's looking back to a

better time religiously. As to racism and feminism and the other issues, he's

not addressing them. You're bringing that in. That's outside the novel.

#2

Irene, I've been thinking

all day (while knocking myself out with yard work) on what you said above. I

guess your underlying assumption is that it was secular humanitarianism that

ended racism and restrictions to women. Perhaps I might agree on the feminism,

but I would say it was clearly not in racism. Ending of slavery and creating

civil rights came from religious impulses, not secular. We know the

abolitionists both in this country and worldwide were religious Christians. Dr.

Martin Luther King was a reverend. Bartolomé de las Casas was a Dominican friar

who advocated rights and humanity for the indigenous people in the new world.

As to women's liberation,

well, that has more to do with the nature of the family and the structure of

work. Throughout history most women have not advocated structural relationship

changes to their status. They may have advocated ending some injustices, but

not their role in society. If you ask me, the destruction of the family because

of where feminists have taken their liberation has been pernicious to society

and to women.

#3

Back to the novel,

Irene's comment made me realize that none of the government officials are women

or minorities. Felsenburgh, Oliver, Phillips, Lord Pemberton, Snowford,

Markham, all males and presumably white. No one is even conscious of this issue

in 1907.

Different issue. I wonder

if Felsenburgh's first name of Julian is supposed to allude to Julian the

Apostate, the Roman emperor back in the fourth century that tried to reverse

Christianity as the religion of the empire and return it back to its pagan

roots? Plausible.

#4

@ Irene, ah now I see.

Yes I want modern amenities too! Especially modern nutrition and medicine.

Agree. Heck I'm an engineer!

Two thoughts on that.

(1) The point is values

difference between old world and new. It's a narrative and to make a rhetorical

point he has to used contrast of different worlds. I would not be surprised if

Benson would agree with that.

(2) From the perspective

of 1907, Benson has not seen or experienced the dramatic improvements in health

that we have seen in this past century. Look at this life expectancy chart:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Life_ex...

It was relatively flat

until Benson's lifetime, or maybe in Europe the generation before him. He

doesn't have the same appreciation we have for health improvements.

I don't think Benson's

point is that he would prefer the old world over the new based on the lack of

innovation. I think his point is that if the new world requires shucking off

belief in God, then it's not worth it.

My

Reply to Kerstin on the Modern Architecture:

Yes, but I don't know if

he's addressing that either. In 1907 they still hadn't seen the horrific

architecture of the 20th century, especially that in the communist countries.

Perhaps there is a relationship between socialism and these ugly structures on

some psychological level, but this is still before Benson could conceptualize

it. The Victorian era ended in 1901, so he was still a product of an emphasis

on beauty. We're still in an era of impressionism in the arts. Modernistic art

to some degree was a reaction against Victorian aesthetics.

But now that I've written

that, I'm curious whether Benson had some indication. In some respects,

Benson's philosophy is a repudiation of H. G. Wells, and Wells was writing in

the 1890s. I keep saying that the contrasting philosophy is

"modernism" but technically what has been called

"modernism" didn't really get formed until after WWI. But in late

Victorianism and in those early decades of the 20th century, the contrasting

philosophy of what might be called progressive was called "futurism."

It was socialist in politics and Utopian in vision. Futurism and modernism are

nearly synonymous.

I guess what I'm trying

to say is that futurism had not made its impact on the arts but its

intellectual underpinnings were around. Nietzsche, Marx, Freud, they were all

there an shaping the intellectual culture.