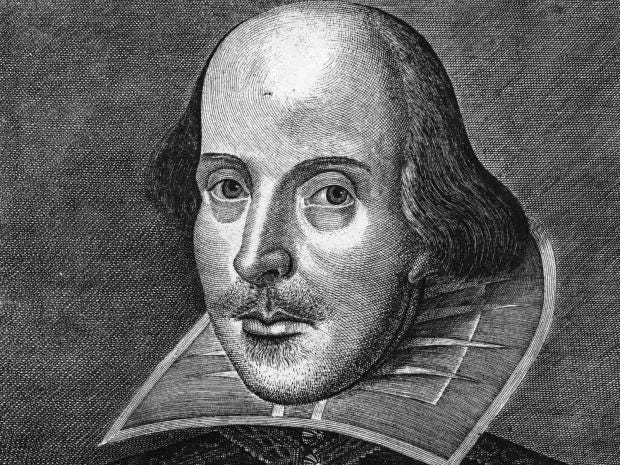

I have finally gotten

around to reading one of William Shakespeare’s Henry

VI plays, and of course one starts with the first of the trilogy. For the record, I’ve now read 29 of the 37 authentically

identified Shakespearian plays. A good

portion of the unread plays happen to be Histories. If you are unaware, critics categorize the

Bard’s play into Comedies, Tragedies, and Histories. I’ve read all the great history plays: Richard III, Richard II, the two Henry IV plays, and Henry V. What’s left are the

three Henry VI plays, King John, and Henry VIII, all lesser plays in stature and reputation. Scratch one of the Henry VI off. Admittedly it’s

hard to motivate to read the lesser plays given one has come to appreciate the

wonder of the great plays, but still one has to complete them all. Some people have bucket lists of traveling

across the world; my bucket list consists of reading all of Shakespeare.

Most people are more

familiar with the great tragedies, since they are probably forced to read those

in school. And it’s true, there is

something beyond superlative in Shakespeare’s tragedies. They were absolutely groundbreaking in form

and range. But Shakespeare’s great comedies

and histories are also head-and-shoulders above what was written in his day,

and perhaps outside of France’s Moliere, you cannot find another playwright

until several hundred years later with Ibsen and Strindberg that has as many great

dramas as Shakespeare. Shakespeare’s great

comedies and histories also stand with greats of their respective genre.

The

reason I decided to read Henry VI was

mentioned back in the first post I wrote on Mark Twain’s Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc and that is because the same historical

events are part of both works. Indeed, the

historical figures are in both, and since the historical events were fresh in

my mind it would make sense. Plus I was

curious how Shakespeare would portray Joan, and I’ll get to that eventually.

Now

it’s quite possible that Henry VI, Part 1

was Shakespeare’s first complete drama, and as the Wikipedia entry states, he

may have had some help by either Christopher Marlowe and/or Thomas Nashe, both

dramatists in Shakespeare’s day. It’s

quite possible. The Shakespeare-Online site – a very good resource and way better than

some of the other Shakespeare sites on the web—suspects that someone other than

the Bard crafted Joan of Arc’s speeches.

There may be something to that. Most of the language in the play certainly

rings of Shakespeare’s voice, except for Joan.

I can’t put my finger on it, but Joan does not sound like a

Shakespearean character. Again, more on

Joan later.

Given

it was Shakespeare’s first play, one sees some of the inexperience, but one

sees some real great flourishes as well.

That scene in Act II, Scene IV where the nobles of York and Lancaster

pluck white and red roses off a bush, setting in motion the seeds of the War ofthe Roses, is brilliant. The poetic flourishes can rise with the

greatest of Shakespeare’s. For instance,

the play begins with the dead body of the heroic King Henry V, and the Dukes of

Bedford and Gloucester eulogize in sweeping language to capture the greatness

of the fallen man. From the plays very

opening lines in Act I, Scene 1:

BEDFORD Hung be the heavens with black, yield day

to night!

Comets, importing change

of times and states,

Brandish your crystal

tresses in the sky,

And with them scourge the

bad revolting stars

That have consented unto

Henry's death! 5

King Henry the Fifth, too

famous to live long!

England ne'er lost a king

of so much worth.

GLOUCESTER England ne'er had a king until his

time.

Virtue he had, deserving

to command:

His brandish'd sword did

blind men with his beams: 10

His arms spread wider

than a dragon's wings;

His sparking eyes,

replete with wrathful fire,

More dazzled and drove

back his enemies

Than mid-day sun fierce bent

against their faces.

What should I say? his

deeds exceed all speech: 15

He ne'er lift up his hand

but conquered.

I’m

using the online text at Shakespeare-Online for this and all subsequent quotes.

And

so we have of the great King Henry V, model of leadership, soldiery, and virtue

to be contrasted with the King VI and the governing aristocracy. Now Henry VI has somewhat of an excuse, he’s rather young.

Shakespeare doesn’t quite follow the time scale; Henry VI was less than

a year old when his father died, and the events of the drama would have occurred

when Henry VI would have been about nine years old. He was a child king, under the Protectorate

of the Duke of Gloucester. But in the

play he sounds more like a teenager than a nine year old. I have never seen this acted out, so I don’t

know how directors cast it.

It

is a long play, with an exorbitant number of characters, thirty-five in all,

not including attendants and messengers, and of course the armies of soldiers. Perhaps that is what speaks to Shakespeare’s

inexperience the most. After a while I

could not recall the distinction between the Earls of Warwick, Somerset,

Suffolk, Salisbury, and so on. They

became a sort of blur, and perhaps are under characterized, even though it’s a

long play.

What

makes it a long play are the divisions.

First off there is the division between the French and the English

fighting over the French territories. But

what speaks to the play’s central theme are the divisions and hostilities

within the English side. There is the

division inside the English King’s court fighting over the influence on the

child king. Then there is a secular verses ecclesiastical division. There is a subtle division between lords in

England with the English fighting in France on how to fight the war. And of course there is the great division

between the Houses of York and Lancaster that will blossom into the War of the

Roses. That may be following the history

of the events, but it does make it difficult to follow. But as it turns out, this was a popular play

in its day, so perhaps the divisions were second nature to the contemporary

audience, enough so that they could easily follow it.

This

division on the English side is dramatized early on in what seems a rather

unimportant little scene. Gloucester,

the Lord Protector of the realm as overseer of the child king, comes to London

Tower, which I believe was the royal palace, and is prevented from

entering. Here’s the beginning of Act I Scene

3:

London. Before the Tower.

[Enter GLOUCESTER, with

his Serving-men in blue coats]

GLOUCESTER I am come to survey the Tower this

day:

Since Henry's death, I

fear, there is conveyance.

Where be these warders,

that they wait not here?

Open the gates; 'tis

Gloucester that calls.

First Warder [Within] Who's there that knocks so imperiously? 5

First Serving-Man It is the noble Duke of Gloucester.

Second Warder [Within] Whoe'er he be, you may not

be let in.

First Serving-Man Villains, answer you so the lord

protector?

First Warder [Within] The Lord protect him! so we answer

him:

We do no otherwise than

we are will'd. 10

GLOUCESTER Who willed you? or whose will stands

but mine?

There's none protector of

the realm but I.

Break up the gates, I'll

be your warrantize.

Shall I be flouted thus

by dunghill grooms?

[ Gloucester's men rush

at the Tower Gates, and WOODVILE the Lieutenant speaks within ]

WOODVILE What noise is this? what traitors have we

here? 15

GLOUCESTER Lieutenant, is it you whose voice I

hear?

Open the gates; here's

Gloucester that would enter.

WOODVILE Have patience, noble duke; I may not open;

The Cardinal of

Winchester forbids:

From him I have express

commandment 20

That thou nor none of

thine shall be let in.

GLOUCESTER Faint-hearted Woodvile, prizest him

'fore me?

Arrogant Winchester, that

haughty prelate,

Whom Henry, our late

sovereign, ne'er could brook?

Thou art no friend to God

or to the king: 25

Open the gates, or I'll

shut thee out shortly.

Serving-Men Open the gates unto the lord protector,

Or we'll burst them open,

if that you come not quickly.

And

so after the scene eulogizing Henry V (scene 1), and a scene where the French resistance

unifies in strategy around Joan (scene 2), we get a scene where the highest

lord in England other than the child king is blocked by the Cardinal of

Winchester from entering the seat of government. But notice the stage directions right after

Gloucester’s words above: “[Enter to the Protector at the Tower Gates BISHOP OF

WINCHESTER and his men in tawny coats].”

So the Bishop’s men have tawny coats which contrast with the blue coats

(see the stage directions at the beginning quoted above). Blue coats verses tawny coats, white rose

verses red rose, English banners verses French banners, the divisions are

visually laid out for the audience.

I’m

not going to present details of the various divisions; I think you now have the

key to the play. The divisions are made

possible because the weakness of the king.

That’s not to say that Henry VI doesn’t say the right things. He does, for instance here when once again Gloucester

and Winchester are at each other’s throats:

KING HENRY VI Uncles of Gloucester and of Winchester,

The special watchmen of

our English weal,

I would prevail, if

prayers might prevail, 70

To join your hearts in

love and amity.

O, what a scandal is it

to our crown,

That two such noble peers

as ye should jar!

Believe me, lords, my

tender years can tell

Civil dissension is a

viperous worm 75

That gnaws the bowels of

the commonwealth.

(III.1:65-73)

Yes

exactly, it “gnaws the bowels of the commonwealth.” And do they stop in that very scene? No. Gloucester,

in Machiavellian mode, offers his hand of peace to Winchester, who at first

refuses, but then in counter Machivellian mode, accepts it with an aside snark,

“[Aside] So help me God, as I intend it not!” (III.1: 141). And the King in all his innocence is gleeful.

KING HENRY VI O, loving uncle, kind Duke of Gloucester,

How joyful am I made by

this contract!

Away, my masters! trouble

us no more;

But join in friendship,

as your lords have done.

(III.1: 142-145)

Join

in what friendship? There is only

friendship within the various factions, but the seeds of the realm’s chaos are

sown.

And

the fruits of these divisions are being born on the battlefields of France,

where the English, despite heroic effort, are being defeated. The French through Joan take Orléans and

Reims, and Charles VIII, the Dauphin, is crowned King of France. The heroism of the English fighting in France

is dramatized through the fighting and death of John Talbot, the Earl of

Shrewsbury, and his son, young John.

Before the battle at Bourdeaux, with the English facing annihilation, old

John tries to send young John away from the battle to avoid certain death. Young John refuses and wishes to die if he

must fighting with his father. The

exchange is delineated in rhyming couplets.

Here’s a sample:

TALBOT Shall all thy mother's hopes lie in one

tomb?

JOHN TALBOT Ay, rather than I'll shame my mother's

womb. 35

TALBOT Upon my blessing, I command thee go.

JOHN TALBOT To fight I will, but not to fly the

foe.

TALBOT Part of thy father may be saved in thee.

JOHN TALBOT No part of him but will be shame in me.

TALBOT Thou never hadst renown, nor canst not

lose it. 40

JOHN TALBOT Yes, your renowned name: shall flight

abuse it?

TALBOT Thy father's charge shall clear thee

from that stain.

JOHN TALBOT You cannot witness for me, being slain.

If death be so apparent,

then both fly.

TALBOT And leave my followers here to fight and

die? 45

My age was never tainted

with such shame.

JOHN TALBOT And shall my youth be guilty of such

blame?

No more can I be sever'd

from your side,

Than can yourself

yourself in twain divide:

Stay, go, do what you

will, the like do I; 50

For live I will not, if

my father die.

TALBOT Then here I take my leave of thee, fair

son,

Born to eclipse thy life

this afternoon.

Come, side by side

together live and die.

And soul with soul from

France to heaven fly. 55

(IV.5: 34-55)

Why

the couplets? I think it’s there to

imply disagreement in love rather than division and discord. And then at the battle, old Talbot comes into

the scene mortally wounded and asks for his son.

[Enter Soldiers, with the body of JOHN

TALBOT]

TALBOT Thou antic death, which laugh'st us here

to scorn,

Anon, from thy insulting

tyranny,

Coupled in bonds of

perpetuity, 20

Two Talbots, winged

through the lither sky,

In thy despite shall

'scape mortality.

O, thou, whose wounds

become hard-favour'd death,

Speak to thy father ere

thou yield thy breath!

Brave death by speaking,

whether he will or no; 25

Imagine him a Frenchman

and thy foe.

Poor boy! he smiles,

methinks, as who should say,

Had death been French,

then death had died to-day.

Come, come and lay him in

his father's arms:

My spirit can no longer

bear these harms. 30

Soldiers, adieu! I have

what I would have,

Now my old arms are young

John Talbot's grave.

[Dies]

(IV.7: 18-32)

What

a visually dramatic moment that is, father and son dead in each other’s arms.

As

to Joan of Arc, or Joan La Pucelle as she is mostly referred to in the play,

one has to be disappointed. “La Pucelle”

translates into “the maid.” Shakespeare

took the common English view as Joan as some sort of sorceress, but I guess

what other view could he have taken? This

is supposedly haw she is portrayed in Holinshed's Chronicles, Shakespeare’s source for English history. But she is more than a sorceress. At first she is an Amazon. She isn’t just a strategist and inspirational

leader, she wields a sword and fights real duels. Here is the exchange between Joan and the

Dauphin when they first meet and she convinces him of her supernatural

abilities.

JOAN LA PUCELLE Dauphin, I am by birth a shepherd's

daughter,

My wit untrain'd in any

kind of art.

Heaven and our Lady

gracious hath it pleased 75

To shine on my

contemptible estate:

Lo, whilst I waited on my

tender lambs,

And to sun's parching

heat display'd my cheeks,

God's mother deigned to

appear to me

And in a vision full of

majesty 80

Will'd me to leave my

base vocation

And free my country from

calamity:

Her aid she promised and

assured success:

In complete glory she

reveal'd herself;

And, whereas I was black

and swart before, 85

With those clear rays

which she infused on me

That beauty am I bless'd

with which you see.

Ask me what question thou

canst possible,

And I will answer

unpremeditated:

My courage try by combat,

if thou darest, 90

And thou shalt find that

I exceed my sex.

Resolve on this, thou

shalt be fortunate,

If thou receive me for

thy warlike mate.

CHARLES Thou hast astonish'd me with thy high

terms:

Only this proof I'll of

thy valour make, 95

In single combat thou

shalt buckle with me,

And if thou vanquishest,

thy words are true;

Otherwise I renounce all

confidence.

JOAN LA PUCELLE I am prepared: here is my keen-edged

sword,

Deck'd with five

flower-de-luces on each side; 100

The which at Touraine, in

Saint Katharine's

churchyard,

Out of a great deal of

old iron I chose forth.

CHARLES Then come, o' God's name; I fear no woman.

JOAN LA PUCELLE And while I live, I'll ne'er fly

from a man. 105

[Here they fight, and

JOAN LA PUCELLE overcomes]

CHARLES Stay, stay thy hands! thou art an Amazon

And fightest with the

sword of Deborah.

JOAN LA PUCELLE Christ's mother helps me, else I

were too weak.

(I.2: 73-108)

This

isn’t the only place she overcomes men in a physical bout. It’s interesting that the Blessed Mother is

invoked as the source of her strength. This

might have raised eyebrows in Protestant, Elizabethan London, and probably

would have been a signal to the audience to disdain her. Notice too there is a suggestion of future sexual

liaison between the two (“warlike mate”) which gets expanded a little further

in the scene. But the French do put

faith in her as sent from Providence.

Indeed the religious faith of the French contrast with secular/religious

division of the English side, and may have been a reflection of Shakespeare’s contemporaries. For I’m convinced that Shakespeare was a

closet “papist” as one neighbor of his in his home town of Stratford-upon-Avon

famously said after Shakespeare had died.

Frankly

I find the delineation of Joan’s character altogether baffling. One moment she is an Amazon, another a saint,

another a witch, another a strumpet, another a liar as she tries to escape

execution. Though she contrives

victories for most of the play, her powers suddenly cease, and she is

captured. As I said above, her character

does not feel it came from Shakespeare’s hand.

With

Joan’s capture and the hostilities between the English and French come to an

end, the play concludes. The

French/English division is resolved, but none of the other divisions get

resolved. They are left hanging, but of

course this is the first part of a trilogy.

The next two parts of Henry VI

will resolve those loose ends.

Manny, you are a learned man, and I shall ask you some questions which, believe me, are serious ones. I am not being facetious.

ReplyDeleteDid people in Shakespeare's time speak as in his plays? For example:

GLOUCESTER: I am come to survey the Tower this day:

Since Henry's death, I fear, there is conveyance.

Where be these warders, that they wait not here?

Open the gates; 'tis Gloucester that calls.

Today, people would say: I am Gloucester and I have come to check how you transport the prisoners to and from the Tower. Where are the guards?

Did just the well-to-do people speak like this? Or everyone? Who exactly attended his plays? Because the poorer uneducated folks would not understand a word of what he says; assuming they could afford to see his plays.

God bless.

That's a great question Victor, and the answer is a little complicated. First every word there would probably be words the average Englishman of the day would know. So in that sense, yes.

DeleteSecond, Shakespeare is writing in poetry, so the speech is heightened from ordinary language. Because Shakespeare is such a master, it comes across as common speech, but it is not. So no, in that respect. Shakespeare does have scenes where the poetry drops and it becomes colloquial, and characters speak the way the average person would sound in that day, but those are not the majority of scenes.

Third, we English speakers of the last hundred years have developed an ear for minimizing the number of words. Some writers like Hemingway, are actually called minimalists. It has not always been that way, and Shakespeare loves to be verbose. I call Shakespeare a "maximalist." Some people judge verbose writers detrimentally. I like to point out Shakespeare and say it's not whether you are a minimalist or a maximalist; it's how well you use the language. So Shakespeare is probably more verbose than the average person of today and probably of his day.

Hope that helps.

Thank you, Manny. As you know, I do not like Shakespeare because he was forced on me at school and college and I had to memorise a lot of his nonsense for exams. Today, I do not read any of his books because he does not read mine.

DeleteHaving said that, I enjoyed Chaucer very much and read all his Canterbury Tales, some in the original English. He was not a verbose maximalist as Shakespeare. I went to see his grave at Wesminster Abbey in London and visited Canterbury Cathedral.

You don't seem to write a lot about Chaucer. What has he ever done to upset you?

God bless.

Oh I would love to have seen Chaucer's grave. I love Chaucer too. I've wanted to post something on Chaucer but just haven't gotten around to re-reading him lately. I promise I will do so in the new year. Happy New Year Victor.

Delete