On

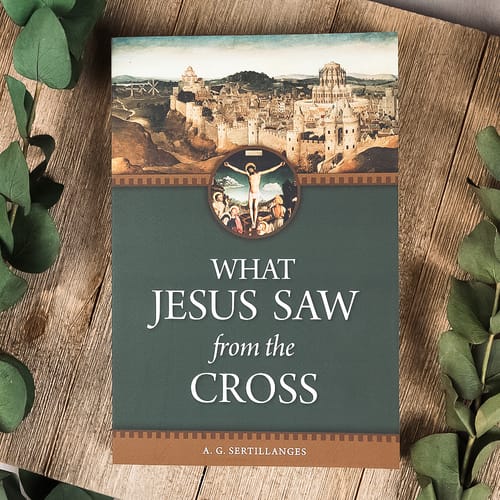

Ash Wednesday I mentioned I was reading What

Jesus Saw from the Cross by A. G. Sertillanges for Lent, and I have to say this is

one of the best devotional books I have ever read. Perhaps it’s the very best devotional I have

ever read. As I said then, Sertillanges contemplates

what Jesus saw and thinks as He is pinned upon the cross, meditating on the

Passion events.

Not

only are the meditations profound, but the writing is superb! Here’s for your appreciation an extended

quote from the passage where the crowd turns against Jesus. Notice how Sertillanges shifts subtly perspectives

from Pilate to Jesus to the crowd several times to create different angles,

perceptions, and views. Notice how he

changes the pacing of the syntax, accelerating as the actions and emotions

build, slowly down to provide contemplative commentary. This passage, and along with many other

passages in the book, are truly passages I wished I had written. Sertillanges, a French Dominican friar, had

written the work in his native tongue, but whoever translated it—it doesn’t say

in my Sophia Institute Press 1996 edition—did a remarkable job. There is a note on the copyright page that

says the book “was published in French as Ce

Jésus voyait du haut de la croix by Ernest Flammarion of Paris in

1930. An English translation was

published by Clonmore & Reynolds Ltd. in Dublin in 1948.”

Not

only are the meditations profound, but the writing is superb! Here’s for your appreciation an extended

quote from the passage where the crowd turns against Jesus. Notice how Sertillanges shifts subtly perspectives

from Pilate to Jesus to the crowd several times to create different angles,

perceptions, and views. Notice how he

changes the pacing of the syntax, accelerating as the actions and emotions

build, slowly down to provide contemplative commentary. This passage, and along with many other

passages in the book, are truly passages I wished I had written. Sertillanges, a French Dominican friar, had

written the work in his native tongue, but whoever translated it—it doesn’t say

in my Sophia Institute Press 1996 edition—did a remarkable job. There is a note on the copyright page that

says the book “was published in French as Ce

Jésus voyait du haut de la croix by Ernest Flammarion of Paris in

1930. An English translation was

published by Clonmore & Reynolds Ltd. in Dublin in 1948.”

Here is the passage, taken from the chapter titled, "His Enemies."

The incredible thing is

that it should have been found possible to mobilize against Jesus so many

people who for various reasons ought to have been His friends. They had received from Him nothing but

benefits. His word had awaken their

slumbering hearts; His goodness had won their affection; His miracles had

aroused their admiration; His condemnation of abuses could not but command

their sympathy; and His promises of happiness, even if they were not believed,

must at least have flattered their dreams.

What is their grievance? That the leaders of the Jews should have

hated Jesus is perhaps intelligible, but the enmity of the crowd is most

mysterious. It is only at the last

moment that it becomes manifest, and then only under the stimulus of

encouragement from the priests.

At the beginning of His

sacred ministry Jesus had applied to Himself the words of the prophet: The

spirit of the Lord is upon me, wherefore He hath anointed me to preach the

gospel to the poor. He hath sent me to

heal the contrite of heart, to preach deliverance to the captives, and sight to

the blind, to set at liberty them that are bruised, to preach the acceptable

year of the Lord, and the day of reward (Luke 4:18; Cf. Isa 61:1-2).

This program had aroused

intense enthusiasm. It is true that

there was annoyance at some of His reproaches, and that among His own people

Jesus had already experienced something of the fickle moods of mankind. Still, on the whole He had been well received

by the masses.

If Jesus complained of

their tepidity and their incredulity, of their selfishness and their demands,

He did not attribute hostile sentiments to His hearers. Often He had been acclaimed; they had wanted to

make Him king. He was received and welcomed

with gratitude, and during the last few days since the raising of Lazarus,

their love for Him seemed to have reached its zenith.

“A great prophet has

arisen in the midst of us! God has

visited His people! He has done all

things well! Never has man spoken as

this man! He is Elijah! He is John the Baptist risen again, or one of

the prophets! He is the messiah: Hosanna

to the son of David! Blessed is he that

cometh in the name of the Lord! Such

were the cries that saluted Him.

Even during the Passion

itself, at Pilate’s house, the crowd does not seem ill disposed at first. The leaders had not summoned them; it was

hardly likely! Had it not been for Judas

and the opportunity he offered, they would willingly have postponed the

satisfaction of their hate to avoid this concourse. “Not on the festival day,” they said, “lest

there be a tumult among the people (Matt 26:5).

The crowd has assembled

for reasons of its own. They have a

right to have a prisoner released to them this day, and they are going to claim

that right. Perhaps they are thinking of

Barabbas, perhaps of Jesus, who is at this moment is appearing before the

tribunal (Mark 15:11-13).

Unhappily for the popular

choice or for its constancy, the leaders take a hand; they have time to do so,

for this is the interval during which the procurator’s wife interrupts the

proceedings. The mutual explanations of

the pair must have taken a moment or two, and it was natural that a certain

time should be allowed to claimants to decide upon their choice.

Pilate has just given

them the option: “Which of the two will you that I release unto you?” And he has shown them in which direction his

own inclination lies: “Will you that I release unto you the king of the Jews”

(Mark 15:9)? Left to themselves, those

in the crowd might answer in the affirmative, but the leaders are rousing them

now; their high priests have control over them, in spite of their

complaints. Moreover, Pilate has

irritated them by twice referring jocularly to “their king” (Mark 15:9,

12).

King, king, always the

king! And a broken-down king at

that! He rouses their derision more than

their pity: a Messiah in chains before a Roman governor! This seems to be the kernel of the matter in

the eyes of these Israelites, who yesterday were enthusiastic, a few moments

ago were in doubt, and now are suddenly hostile and furious.

Mobs do not like to be

disillusioned; and the man who disappoints them may pass in a moment from the

rank of a national hero to nothing, and even to less than nothing. The sympathies of the mob are liable to

revulsions. Many a crashing fall in

history has been due to no more than this.

Think what a

disillusionment it is for the Jews to see Jesus in this condition before

Pilate, to say nothing of the other accusations against Him to which that

condition easily lent credit. The

Liberator of the chosen people appearing as a leader of sedition before a Roman

tribunal and unable to acquit himself of the charge! This is the Pualine “scandal of the Cross”

(Cf. 1 Cor 1:23) by anticipation, and we can understand that an infuriated crowd

will leave Him to His fate.

From disappointment they

pass to spite, from spite to anger, and under the ceaseless encouragement of

their iniquitous leaders they are easily roused to exasperation. The word cross

has been spoken; it is taken up and repeated.

The penalty of crucifixion has been so often inflicted on Jews that they

are surprised at the hesitation of the governor. Once they have rejected Jesus, He is nothing

more nor less for them than an agitator and an enemy of the empire. “What you have done to so many others,” they

answer in reply, “Crucify Him!” (Matt 27:22; Mark 15:13; Luke 23:20-21; John

19:15)

Once the change of

feeling is thus achieved, the taste of blood now begins to intoxicate the mob;

a thrill of cruelty runs through them all.

To any further questions or objections the maddened crowd has only one

reply, given with increasing violence: “Crucify Him! Crucify Him!”

And it does not stop there; it involves the whole people in its own

responsibility, and not only the present generation but posterity as well: “His

blood be upon us and upon our children!” (Matt 27:25)

And that prayer will be

answered. But what a tragedy for Him who

would have gathered this thankless people “as the hen gathers her chicken under

her wing!” (Matt 23:37; Luke 13:34) He

has come to them with a message of happiness, and they hate Him and

blaspheme. If that message was only a

dream it was at any rate a dream of goodness; and their only answer is the

nightmare of death.

This people, which has

awaited and expected Him for many centuries, receives Him and fails to know Him

for what He is. He who was to come is

come, and He departs carrying all His blessings with Him. His nation scorns Him, kills him, drives Him

forth; even dead they will have Him only outside their walls. And while He dies they scoff and sneer. Even those who have not come to see Him die

are over there on the terraces of their houses, waving their arms and crying

out like madmen. And Jesus, whose Cross

raises Him above the level of the walls, can see these traitors to His love,

these distant enemies.

As the procession passed

the Gate of Ephraim, those who had been waiting there since the great news came

from the praetorium, who had heard the legal formula “Go, lector, prepare the cross!” pronounced, must have broken forth

again into tumultuous fury. For now it

was their fury that they showed, not their desires or their requests. The cruel gaiety of this day had gone to

everybody’s head; the word cross was

on the lips of them all, and the word blood

and the word death, mingled with Galilean, rabbi, prophet, Messiah; and every word was uttered with

a sneer.

Every savage instinct

latent in the heart of man was awake; souls frothed over with rage, and this

anticipatory delegation of those who in every generation would hate and oppose

Christ, vented itself in a cry of satanic joy.

The darkness and the

other portents that are soon to appear will damp this delirious frenzy. A thrill of fear will pass through the city;

hearts will be heavy; those who now acclaim the death of the Savior will beat

their breasts. Once more the fickle

crowd will change, in its emotional and childish fashion. Yet the problem still remains: how did this

transformation which we have described become possible? General explanations do not satisfy the mind;

is there not one which perhaps goes deep to the heart of things? (pp. 156-61)