This

is third post on the short story analysis of Flannery O’Connor’s, “The

Displaced Person.” You can read Post #1

here.

And

Post #2 here.

After

Mrs. McIntyre has decided to let Mr. Guizac go, O’Connor then turns the screw on

the tension. Mr. Shortley, the longtime worker

who had left the farm with his wife and children at the end of Part I, returns. He was the head farm hand that felt displaced

when Mr. Guizac was outperforming him. As

it turned out, his wife, Mrs. Shortley, had a stroke and died that very day

they took off, and her husband blames her death on the stress she felt from the

immigrant superseding her husband on the farm pecking order. Mr. Shortley represents the aggrieved

American worker displaced by the immigrant.

He is native, he understands the cultural norms of the home region, he

has long worked the farm, his wife’s death reveals his suffering because of the

stranger, and he served in the army during the war defending the country. In his character, O’Connor builds a moral

standing to contrast the moral standing of the immigrant.

It took Mrs. McIntyre

three days to get over Mrs. Shortley’s death. She told herself that anyone

would have thought they were kin. She rehired Mr. Shortley to do farm work

though actually she didn’t want him without his wife. She told him she was

going to give thirty days’ notice to the Displaced Person at the end of the month

and that then he could have his job back in the dairy. Mr. Shortley preferred the

dairy job but he was willing to wait. He said it would give him some satisfaction

to see the Pole leave the place, and Mrs. McIntyre said it would give her a

great deal of satisfaction. She confessed that she should have been content

with the help she had in

the first place and not have been reaching into other parts of the world for

it. Mr. Shortley said he never had cared for foreigners since he had been in

the first world’s war and seen what they were like. He said he had seen all

kinds then but that none of them were like us. He said he recalled the face of

one man who had thrown a hand-grenade at him and that the man had had little round

eye-glasses exactly like Mr. Guizac’s.

“But Mr. Guizac is a

Pole, he’s not a German,” Mrs. McIntyre said.

“It ain’t a great deal of difference in them two kinds,” Mr. Shortley had explained. (p. 227)

O’Connor here shows us the tribal bonds between Shortley and Mrs. McIntyre; she recalls the friendship bonds with Mrs. Shortley, and, though she can’t hire Mr. Shortley immediately to his old job until she has let Mr. Guizac go, retains him until that job is available. The gist of the situation is that Mrs. McIntyre is now obligated to carry through on the thirty-day notice for Mr. Guizac.

###

Part III then begins with a tightening of the conflict between the moral obligation to care for the displaced (“He has nowhere to go”) and the native born struggling to live out his own life. We see the frictions of culturally different people irritating each other, and the tribal bonds forming in reaction to the outsider. The moral center of the story appears to be in tension. Does the weight of justice lie with Mrs. McIntyre, Mr. Shortley, and the other native farm hands or does the weight lie with Mr. Guizac who outworks everyone else and would be let go only because he is an outsider? Here is where Catholic social doctrine might clarify the matter.

Most Catholic contemporary social thinking starts with

Pope Leo XIII’s Rerum novarum of 1891, but most of the specific thinking on immigrants

and migrants was subsequently developed.

Of particular note is Pope Pius XII’s Exsul Familia

of 1952. That’s within the immediate

cognizance of Flanary O’Connor’s story. Pope

Francis called the Apostolic Constitution (the highest legislative of papal

document forms) the “Magna Carta of the Church’s thinking on migration.” Exsul Familia was certainly in the

Catholic news for O’Connor at the time and could very well have been the

inspiration for this story.

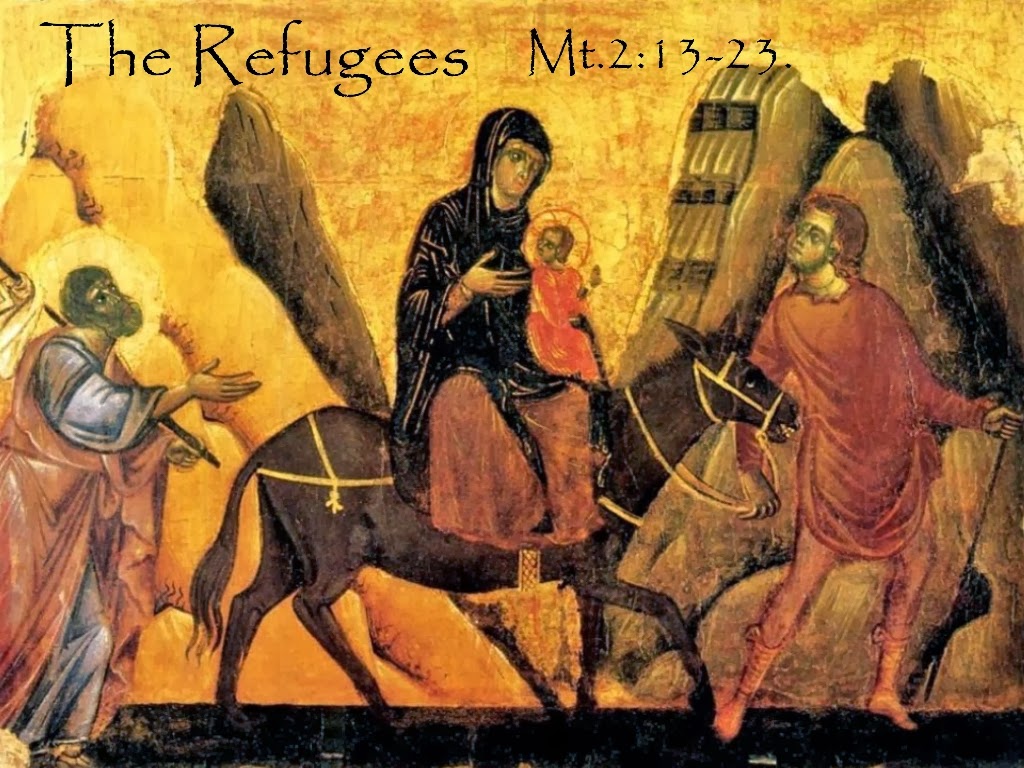

The

opening paragraph of Exsul Familia cites the

Holy Family’s fleeing to Egypt as the model of how to view immigration:

The émigré Holy Family of Nazareth, fleeing into Egypt, is the archetype of every refugee family. Jesus, Mary and Joseph, living in exile in Egypt to escape the fury of an evil king, are, for all times and all places, the models and protectors of every migrant, alien and refugee of whatever kind who, whether compelled by fear of persecution or by want, is forced to leave his native land, his beloved parents and relatives, his close friends, and to seek a foreign soil.

Exsul Familia uses the word “archetype” to describe this model, which not only elevates the model to a particular transcendence but also would be particularly significant for a fiction writer such as O’Connor. It would be impossible to consider that O’Connor would not have taken note and integrated it into her story. Mr. Guizac and his family on Mrs. McIntyre’s farm certainly reflects this Holy Family archetype.

The bulk of Exsul Familia delineates the Church’s history on how it has helped migrants through history. Subsequent popes have distilled the countless historical events on immigrant support into three principles which are articulated in the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) website page under “Catholic Social Teaching on Immigration andthe Movement of Peoples.” The three principles are the following:

(1) People

have the right to migrate to sustain their lives and the lives of their

families.

(2) A

country has the right to regulate its borders and to control immigration.

(3) A country must regulate its borders with justice and mercy.

The

third principle on justice and mercy can be further decomposed to three corollaries:

(3a) Refugees and asylum

seekers should be afforded protection.

(3b) The human dignity

and human rights of undocumented migrants should be respected.

(3c) Even in the case of less urgent migrations, a developed nation's right to limit immigration must be based on justice, mercy, and the common good, not on self-interest.

Notice that it would be inappropriate to limit immigration on “self-interest.” This implies that wealthy countries have a duty to help migrants. Also justice in the Catholic Church’s social doctrine sense does not just mean the mere fair application of laws. It refers to every human being receiving the basic sustenance of shelter and food. The Biblical justification of these principles rest on the archetypical model of the Holy Family, Exodus 22:21 ("You shall not wrong a stranger or oppress him, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt. I am the Lord your God."), Leviticus 19:34 ("You shall treat the stranger who sojourns with you as the native among you, and you shall love him as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt: I am the Lord your God."), Matthew 25:35 ("For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me."), and Hebrews 13:2 ("Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for thereby some have entertained angels unawares."). My emphasis on “stranger” throughout.

One might contrast this open spirit of charity for the stranger with what St. Augustine calls the Ordo amoris, the ordering of the principles of love. What that says is that there are circles of primacy that require more charity than the expanding circles. Your family would have the greatest primacy, then friends and neighbors, then your city, then your country, and finally the farthest reaches of the world. This is a logical application of limited resources, but some use this argument to squash any immigration. Surely the richest country in the world can invite some strangers in need. Self-interest cannot overwhelm justice and mercy.

However

applied, Ordo amoris only addresses charity in an abstract way. It might be useful to establishing a criteria

for how to spend resources and where, but it does not address the needs of the

Holy Family archetype within the borders.

That Holy Family archetype is within your neighborhood, so it’s within a

close circle of charity. Ordo amoris does

not reject the principles that are derived from Exsul Familia but in

some ways support it. Pope Francis, building

on Exsul Familia, derives in his theology of encounter the principle that the migrant is Christ:

The encounter with the migrant, as with every brother and sister in need, “is also an encounter with Christ. He himself said so. It is he who knocks on our door, hungry, thirsty, an outsider, naked, sick and imprisoned, asking to be met and assisted” …Every encounter along the way represents an opportunity to meet the Lord; it is an occasion charged with salvation, because Jesus is present in the sister or brother in need of our help. In this sense, the poor save us, because they enable us to encounter the face of the Lord (cf. Message for the 110th World Day of Migrants and Refugees, September 2024).

Although O’Connor wrote this story well before Pope Francis’s statement, she certainly knew intuitively that the migrant conflates into Christ. Pope Francis is not really saying anything new. Now given that the Church couches its principles on immigration in natural law, these principles then are innate in the hearts of all unless, that is, they harden their hearts against it. O’Connor relies on this in the story.

###

Although

Mrs. McIntyre has resolved to fire him, she does not. Her deadline comes and goes without letting

him go. Shortley observes that

She looked as if something was wearing her down from the inside. She was thinner and more fidgety, and not as sharp as she used to be. She would look at a milk can now and not see how dirty it was and he had seen her lips move when she was not talking. (p. 230)

Mrs.

McIntyre knows what she wants to do but she is in a state of existential tension. The innate Christian principles are bubbling

within her heart. She can harden her

heart, but her conscience is pricking her.

She even has a Biblical type of dream.

There was no reason Mrs. McIntyre should not

fire Mr. Guizac at once but she put it off from day to day. She was worried

about her bills and about her health. She

didn’t sleep at night or when she did she dreamed about the Displaced Person.

She had never discharged anyone before; they had all left her. One night she

dreamed that Mr. Guizac and his family were moving into her house and that she

was moving in with Mr. Shortley. This was too much for her and she woke up and

didn’t sleep again for several nights; and one night she dreamed that the

priest came to call and droned on and on saying, “Dear lady, I know your tender

heart won’t suffer you to turn the porrrrr man out. Think of the thousands of

them, think of the ovens and the boxcars and the camps and the sick children

and Christ Our Lord.”

“He’s extra and he’s

upset the balance around here,” she said, “and I’m a logical practical woman

and there are no ovens here and no camps and no Christ Our Lord and when he

leaves, he’ll make more money. He’ll work at the mill and buy a car and don’t

talk to me—all they want is a car.”

“The ovens and the

boxcars and the sick children,” droned the priest, “and our dear Lord.”

“Just one too many,” she said. (p. 231)

The tension is there in her heart. “Dear lady, I know your tender heart won’t suffer you to turn the porrrrr man out.” And she with her utilitarian view insisting Guizac is not Christ and the priest saying he is.

She wakes up even more determined to let him go. She confronts Guizac in the barn, and she speaks of her bills and he speaks of his. When she suddenly catches a glimpse of a snake in the doorway—is the snake real or a product of her imagination?—she impulsively gets angry and jumps to the disjointed subject that the farm is hers and she can let go anyone she wants. She practically froths at the mouth. “She wiped her mouth with the napkin she had in her hand and walked off, as if she had accomplished what she came for” (p. 232).

But

she did not accomplish what she came for.

Though she got angry, she could not bring herself to fire him. The snake, both a symbol of temptation

(Genesis) and of Christ (Num 21:8-9 and Jn 3:14-15) had pressed on her

heart. Her heart is hardening, but it

has not hardened completely yet. What

finally hardens her heart is the talk about town. Mr. Shortley has been gossiping about her capitulation

to a foreigner, and this has embarrassed her.

Once again she gets herself motivated to let him go.

Mrs. McIntyre found that everybody in town knew Mr. Shortley’s version of her business and that everyone was critical of her conduct. She began to understand that she had a moral obligation to fire the Pole and that she was shirking it because she found it hard to do. She could not stand the increasing guilt any longer and on a cold Saturday morning, she started off after breakfast to fire him. She walked down to the machine shed where she heard him cranking up the tractor.

Interestingly O’Connor has Mrs. McIntyre see it as a moral obligation to let Guizac go. Does she have such a moral obligation? One can see moral obligations to support her long time farm hands. Could her finances support them all? They did at the beginning when Guizac first arrived. What turned Mrs. McIntyre against Guizac were tribal bonds and pricks to her cultural norms. Are these moral reasons for letting a man who works harder and better than the others go? Would it have been moral for the Egyptians to force the Holy Family out based on cultural differences? Would it be moral to turn away Christ if you had hired Him and He had no place to turn? The Catholic social principles on immigration and migrants would say no.

In couching her argument of letting Guizac go as a “moral obligation,” we see the final hardening of Mrs. McIntyre’s heart. If Mrs. McIntyre had never taken on Mr. Guizac as an employee, it would have been understandable. It would have been a prudential decision of pluses and minuses of taking on a foreign worker. But she took him on because he was cheap labor that would supplement her farm. When he worked beyond her imagination, she integrated his life into her establishment. He wasn’t an abstract entity but an embodied person requiring dignity. At this point, she has an additional obligation of willing the good of people she has encountered, of serving those who fall under one’s responsibility. She has encountered a human being in need, and like the Good Samaritan encountering the injured person she must treat him as her neighbor.

###

The

final scene confirms O’Connor’s commitment to Catholic understanding of the

migrant. The displaced person has been

already referred to as a Christ figure. On

her way to finally give him his thirty days’ notice, she finds him working

under the tractor.

Mr. Guizac shouted over the noise of the tractor for the Negro to hand him a screwdriver and when he got it, he turned over on his back on the icy ground and reached up under the machine. She could not see his face, only his feet and legs and trunk sticking impudently out from the side of the tractor. He had on rubber boots that were cracked and splashed with mud. He raised one knee and then lowered it and turned himself slightly.

The

tractor perpendicular to the supine body forms a cross. The raising and lowering of the knee suggests

the adjustment a crucified does as he tries to support himself. Then Mr. Shortley brings another tractor, a

larger tractor, close by and brakes it. Then

the climatic incident.

Mrs. McIntyre was looking fixedly at Mr. Guizac’s legs lying flat on the ground now. She heard the brake on the large tractor slip and, looking up, she saw it move forward, calculating its own path. Later she remembered that she had seen the Negro jump silently out of the way as if a spring in the earth had released him and that she had seen Mr. Shortley turn his head with incredible slowness and stare silently over his shoulder and that she had started to shout to the Displaced Person but that she had not. She had felt her eyes and Mr. Shortley’s eyes and then Negro’s eyes come together in one look that froze them in collusion forever, and she had heard the little noise the Pole made as the tractor wheel broke his backbone. The two men ran forward to help and she fainted.

The Displaced Person is crucified. She awakes to find the ambulance and Fr. Flynn, who gives Guizac a viaticum. Mr. Guizac’s family huddles around him as at the foot of a cross. The ambulance eventually takes the body away.

Though the climax of story involves a crucifixion of sorts, in what way has the Displaced Person actually become a Christ figure? He was given a job; he didn’t work out to the landlord’s satisfaction. Even the “crucifixion” seems to be an accident.

First, Guizac is the stranger as identified in the Biblical passages. And does Mrs. McIntyre treat the stranger per Leviticus, “as the native among you, and you shall love him as yourself”? At first she treats him as a commodity. She is surprised at how profitable her farm now is, and all she can think about is how rich she thinks she can get. She never offers him a raise or have any warmth for him or his family. And once she imagines how rich she can get, she joyfully considers letting all her long time farm help go and replace them with a bunch of Guizacs. She’s ready to displace even the ones who have long worked for her and are tied to the farm. Everyone is just a commodity to her. Guizac is the stranger before her.

Second,

the one thing that is even more powerful than greed to Mrs. McIntyre is her

racism. Her shift in attitude toward

Guizac happens on the discovery of his trying to marry off his white cousin to

the black farmhand. Is it even her

business as to who her farmhand and Guizac’s cousin marry? No, but because it’s a shock to her white,

southern culture Mr. Guizac becomes unacceptable as a farmhand, despite he

being an excellent worker. The “Palm

Sunday” adulation of Guizac being a profitable worker, turns into the passion

narrative of “Good Friday.” When he is a

messiah he is wanted; when he violates some custom, justice is forgotten. In

fact, I think you can think of the story as a condemnation of Southern, racist

and nativist culture not accepting the stranger. We see it with Mrs. Shortley at the beginning

of the story, we see it in Mrs. McIntyre with her shift in attitude, and we see

a particularly nativist and xenophobic attitude in Mr. Shortley. It’s Shortley’s actions that lead to the

crucifixion. Let’s take a look at that

crucifixion scene but now with the events leading to it added.

Mr. Shortley had got on

the large tractor and was backing it out from under the shed. He seemed to be

warmed by it as if its heat and strength sent impulses up through him that he

obeyed instantly. He had headed it toward the small tractor but he braked it on

a slight incline and jumped off and turned back toward the shed. Mrs. McIntyre was looking fixedly at Mr.

Guizac’s legs lying flat on the ground now. She heard the brake on the large

tractor slip and, looking up, she saw it move forward, calculating its own

path. Later she remembered that she had seen the Negro jump silently out of the

way as if a spring in the earth had released him and that she had seen Mr.

Shortley turn his head with incredible slowness and stare silently over his

shoulder and that she had started to shout to the Displaced Person but that she

had not. She had felt her eyes and Mr. Shortley’s eyes and the Negro’s eyes

come together in one look that froze them in collusion forever, and she had

heard the little noise the Pole made as the tractor wheel broke his backbone.

The two men ran forward to help and she fainted.

One small criticism of the story is that there is no willful intent between the characters and the crucifixion. It happens as an accident. But I think O’Connor is aiming to indict more than just a person or two. What impulses is Shortely receiving from tractor that he “obeyed”? What made him park it on the incline beside the tractor Guizac was working under? What made the brake release? What is the “collusion” in the eyes of the characters? It’s all as if some malevolent force was choreographing the events beyond the consciousness of the characters. O’Connor is indicting the racism and xenophobia of her Southern, white culture, and Mr. Guizac, the stranger, the displaced person, the Christ-figure becomes the victim of the culture’s malevolent spirit. He is crucified by the culture not accepting him.

For

the denouement we see Mrs. McIntyre have a nervous breakdown and

hospitalized. Her farm collapses. The hired hands leave and she has to sell off

her cows. She is left with numbness in

her legs, loss of her voice, and near loss of her sight. It seems there is a sort of divine judgment

given to Mrs. McIntyre. She is left

solitary except for one regular visitor.

Not many people

remembered to come out to the country to see her except the old priest. He came

regularly once a week with a bag of breadcrumbs and, after he had fed these to

the peacock, he would come in and sit by the side of her bed and explain the

doctrines of the Church.

Fr. Flynn apparently goes back to her farm to feed the peacocks and try to save her soul. It’s as if he must teach her how to be a Christian.

This

story has presented us with many aspects of Catholic doctrine on migrants and

immigrants. It is a complex story. We have seen the tension that immigrants bring

to native people, and the justice required to both the immigrant and the native. This may be a didactic story, but complexity minimizes

the preachiness that didactic stories have.

In fact, we don’t get a didactic message on whether it’s better to have

immigrants or not. That is left to the

prudential judgement of the reader. What

we see is that once an immigrant is before us, it is required to treat him with

justice and mercy, for that immigrant is the stranger that Christ summons in

Matthew 25:36, and indeed is Christ Himself.

I didn’t think this was such a great story on first read, but as I systematically

analyzed it I found it to be of the highest quality.

No comments:

Post a Comment