This is seventh post of Henryk Sienkiewicz’s

historical novel, Quo Vadis.

You can find Post #1 here.

Post #2, here.

Post #3 here.

Post #4 here.

Post #5 here.

Post #6 here.

Chapters

42 thru 49

Summary

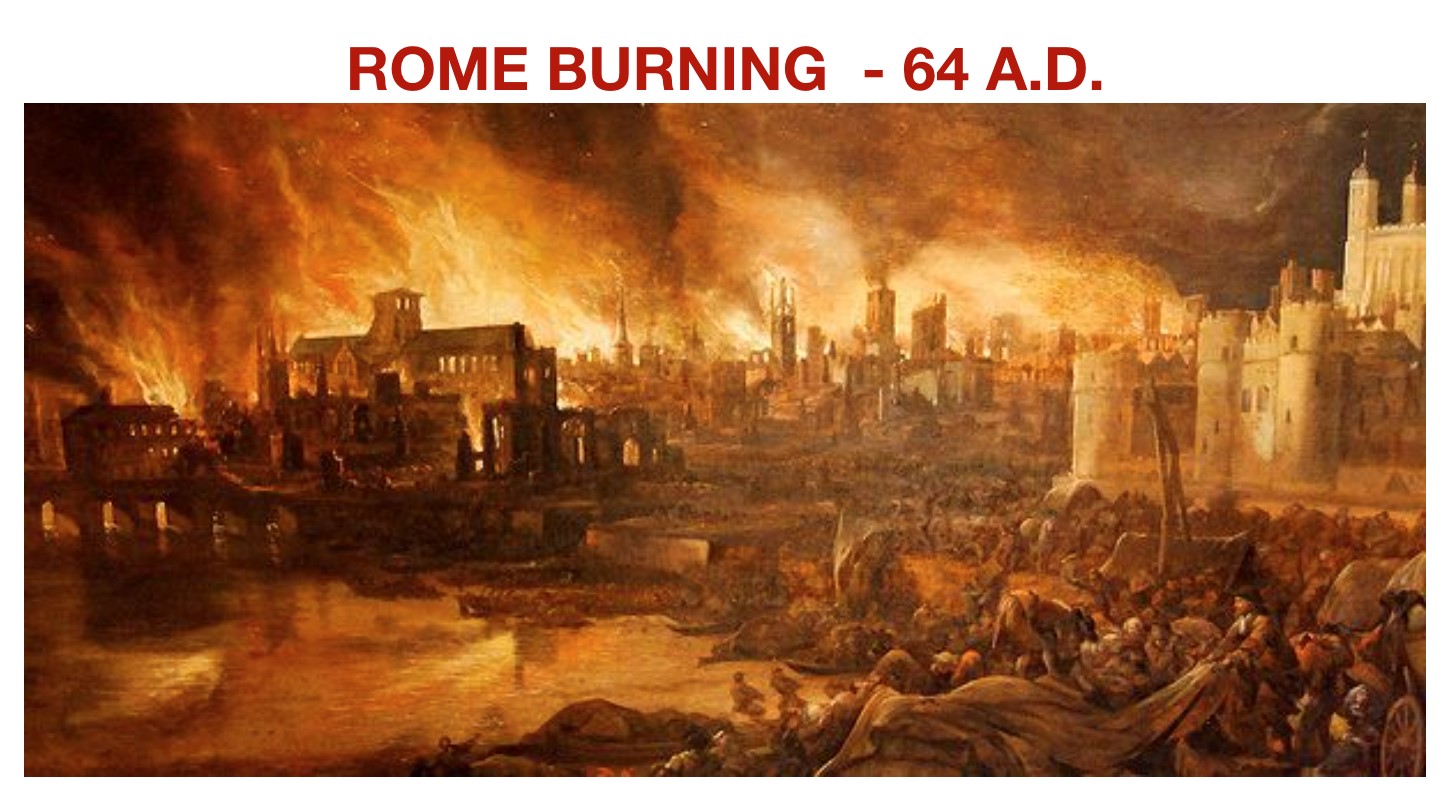

Upon hearing that Rome is ablaze, Vinicius gathers a few of his slaves and a horse and heads for Rome in the dark of night. While riding furiously and with great haste, his thoughts are with Lygia’s safety. He remembers things that Nero had said in court about trying to describe a burning city. He comes to the conclusion that Caesar had ordered the city to burn. The general traffic on the road is heading in the opposite direct, as people are trying to flee Rome. At one moment Vinicius prays to God, the God of the Christians, that if He saves Lygia he will offer himself in sacrifice. As he approaches the city he finds a detachment of praetorians and having a rank of tribune commands them to help him through the crowd. He meets a Senator, Junius, who tells him their homes are burnt, and that this is no ordinary fire but a deliberate one. Vinicius decides to go around the city to come through a different entrance.

When he approaches the wall at the Appian Way, masses of people have encamped or settled in some sort of shelter. People are trampling and fighting and robbing others. Gangs have formed to exploit and victimize refugees. All levels of society have become blurred and languages from all over the world could be heard. The city is burning so bright that the sky seems like daylight but smoke moving with the shifting winds adds to the chaos. The heat from the fire is overwhelming, and so Vinicius decides to head back out and down to the Trans-Tiber. He finds another detachment of soldiers and orders them to fight through the crowd. He is convinced that Nero has started the fire and needs to be overthrown, and he even imagines himself becoming emperor. The crowds at Trans-Tiber are in violent disorder, fighting with each other. His horse is wounded and so he jumps on foot and heads toward Linus’s house. The smoke and the heat are overwhelming but he perseveres. When he reaches Linus’s house, which had not burned, he calls for Lygia, but no one is home. Falling from exhaustion and his tunic smoldering, two men with water come to him. The two are Christians. Suddenly the familiar voice of Chilo comes before him. Chilo tells him he knows where Linus is staying.

The terrible light of a burning city fills the night sky. Fire spreads and starts anew in every neighborhood. Thousands of people are encamped or fleeing. Violence and looting is everywhere while others implore the gods for mercy. Hundreds of burnt bodies lay about. Hardly a family is unaffected; women could be heard screaming in despair, and people do not know where to run. The fire continues to rage and spread, and the city has turned into pandemonium.

Macrinus, one of the Christians who had saved Vinicius, tells him that Linus and the other Christians have gone to Ostrianum. This meant that most of the Christians had been saved from the fire, and he hurries toward Ostrianum. With two mules, he and Chilo go around the city to minimize the clutter from the crowds. Still it is difficult and the conflagration beyond them looks like the end of the world. Vinicius asks Chilo where he was when the fire broke out, and Chilo says by the Circus Maximus, “meditating on Christ.” Chilo tells him that he saw Lygia and the other Christians in Ostrianum before the fire. With suspicion, Vinicius asked him what was he doing there, and Chilo claims he is half Christian now, and the Christians were giving him food. Through the hills, and away from the Jews who had been persecuting the Christians, Chilo leads Vinicius to the Christians where he finds them kneeling and singing hymns. He finds the congregation in prayer and in expectation of Christ’s return as judge. When a roar shakes the earth, the congregation falls to their knees, and at that moment Peter walks in. With Peter’s reassuring words, a calmness pervades, and Vinicius falls to Peter’s knees in supplication.

The city continues to crumble under the flames, and the fire rages further. Tigellinus has been sent to Rome to do what he could. He has houses torn down to try to halt the spreading fire. Whole neighborhoods are destroyed and so are food provisions. Hunger is beginning to spread through the refugees. Tigellinus organizes food to be brought in, but fights start by those trying to loot it. Days continue with thick smoke in the air; the fire is still uncontrolled. Tigellinus sends word to Nero to come since the fire is still a spectacle, and Nero decides to delay so that he could enter at night to better see the fury of the fire. All the while Nero is composing lines of verse describing the burning city. Some of the people along the way cheer him, but most curse him. Clothed in his actor’s wardrobe, he sings his versus to the crowd, and though unmoved by the tragic circumstances of the masses before him, he is delighted with his performance. Both Petronius and Seneca counsel him that he needs to pacify the people. Petronius volunteers to speak to the rabble. After he quiets the crowd, he promises them that Caesar will provide food and games for everyone.

With Peter’s calming words and the fire, while not burnt out, at least ceasing to advance, the Christians return to their temporary dwellings. Vinicius and Chilo follow Peter toward Linus’s house, but Chilo in possession of the mules is directed to take them back to Macrinus. On the way Vinicius asks Peter what else he must do to be ready for baptism, and Peter says “Love men as thy own brothers, for only with love mayest thou serve Him.” As the two approach Linus’s house, Vinicius spots Ursus and Lygia, who is preparing to cook fish. They embrace in another reunion. (How many reunions are we up to now, four?) They exchange informal marriage vows, per the Roman custom. Vinicius then turns to the others and advises to seek safety. Mobs are killing people within the city and Nero may bring troops to establish order. Peter gives permission for others to escape Rome but he must stay with his sheep, the Christians.

Meanwhile back at Rome, it has been a six days and provisions have begun to come in to at least feed the encamped masses. But robbery and violence is still unchecked. The fire is still burning in places, but at least the night sky no longer reflects blood red. The provisions did not appease the masses as they continued to curse Caesar. Of the aristocracy, only Petronius continues to be respected. At Caesar’s court, the aristocrats look to deflect blame for the fire, but to deflect blame from themselves they must also clear Nero. Petronius advises that Nero keep his planned trip to Greece to get out until the Roman anger has subsided. Tigellinus advises the opposite; the Roman senate might declare another emperor. Nero declares that to satisfy vengeance, a victim must be provided. He looks about the room for volunteers. Tigellinus suggests that the Pretorian guard would avenge aristocratic deaths, which shuts Nero up. Just when Nero agrees to go to Greece, Poppaea and Tigellinus propose to blame the Christians. Their deaths can be a spectacle for the public’s blood revenge. In this Petronius saw the danger to his beloved nephew and risks his very life to propose otherwise. He says the truth is the truth and Nero will be blamed by history not just for the fire but for cowardice to live up to it. Tigellinus jumps on this and points Petronius as a traitor. All the aristocrats call to punish Petronius, but Nero holds his hand.

Later, Tigellinus leads Nero over to Poppaea’s section of the palace. With her are two rabbis and Chilo. The rabbis and Chilo agree that the Christians are enemies of the state and started the fire. Chilo speaks of how the philosophy of the Christians leads them exterminate all people and destroy the earth. He gives details how they had done him wrong, particularly one named Glaucus, and how he has now been acquainted with their chief priests. He speaks of how Christians kill children to sprinkle their blood in ceremonies and how they bewitched Nero’s daughter into illness and death. He tells them that Vinicius has become a Christian through Lygia. Tigellinus adds that perhaps Petronius is a Christian too. Chilo tells them he can lead them to where they are all hiding and all their places of worship. Tigellinus proposes to have nephew and uncle immediately killed, but Nero says not now. Chilo is given soldiers to round up the Christians.

###

Some thoughts on these chapters.

These were such an intense set of chapters. The burning of Rome was so well described that it felt I was there. Nero wants to see a burning city so he can describe it better than Virgil’s description. But Nero’s description is a complete failure. But Sienkiewicz’s description in these chapters was truly magnificent, comparable to Virgil’s of Troy. So the irony is that Sienkiewicz does in the novel what Nero wanted to do but couldn’t.

Vinicius’s trek through the burning city for Lygia was a passion procession of suffering akin to Christ’s passion. He even offers himself in sacrifice. It was through this suffering that he earned his initiation into the faith.

Christian compassion is contrasted distinctly against the pagan looting and violence during the burning fire.

I found the drama of Nero’s court as they sought a fall man to blame for the fire just as intense as the description of the burning city. The power play between Tigellinus and Petronius was gripping as they vied for Nero’s approbation. It was a life and death battle.

The love of Petronius for his nephew is a rudimentary—or perhaps a better word would be natural—love akin to Christian love. It is love written in the heart according to natural law. He even puts himself at sacrificial risk of death for Vinicius. If I were to start reading the novel over, I would look for all the bonds of love that hold people together, and all those who like Nero or Poppaea reject those bonds. Chilo has many instances of building a relationship of mutual love and he rejects it. Could we look at the characters as receiving grace to cooperate with God’s love? Again I would look for implications of this on a second read. Vinicius’s conversion is built on the his love for Lygia. I think Peter’s words to Vinicius in chapter 47 is the central theme of the novel: “Love men as thy own brothers, for only with love mayest thou serve Him.”

Chilo is the Judas character. Interestingly Sienkiewicz is playing with a Roman sterotype about never trusting the Greeks. It goes back to Homer who used the Greek’s charade of the Trojan Horse to sack Troy. It continued through the Roman Empire, and indeed into the Middle Ages. During the Crusades, the Latin west routinely claimed the Greeks were untrustworthy. Chilo reminds me of the mestizo character who betrays the Whiskey Priest in Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory. We read that just over two years ago in 2021 for those that participated in that read. That discussion is in our history boards.

###

Michelle

Comment:

Thank you for this great

summary! Chilo was a great source of frustration for me up to this point. I

mean, I expected vile behavior from Nero, Poppaea and Tigellinus, but

opportunistic Chilo liked the Christians. I liked the way Petronius became so

very protective of Vinicius, too.

I hadn't thought of Chilo as a Judas character, but I see that now. Judas also must have cared for and liked his fellow apostles but still betrayed.

Kerstin

Comment:

These are very gripping and intense chapters. The descriptions of the mass chaos were masterfully done. Sienkiewicz focuses for long chapters on the common people, something we don't get out of history books. The juxtaposition to the mad behavior of the singing Nero couldn't be more surreal.

Michelle

Reply:

I was also very impressed

with the realism in those chapters--very easy to imagine what that must have

been like. I imagine it may have been very like the recent conflagration in

Maui.

###

An

excerpt from Chapter 42, Vinicius dashes to the burning city of Rome, and along

the way has the epiphany that Nero was behind the fire..

Vinicius had barely time

to command a few slaves to follow him; then, springing on his horse, he rushed

forth in the deep night along the empty streets toward Laurentum. Through the

influence of the dreadful news he had fallen as it were into frenzy and mental

distraction. At moments he did not know clearly what was happening in his mind;

he had merely the feeling that misfortune was on the horse with him, sitting

behind his shoulders, and shouting in his ears, "Rome is burning!"

that it was lashing his horse and him, urging them toward the fire. Laying his

bare head on the beast's neck, he rushed on, in his single tunic, alone, at

random, not looking ahead, and taking no note of obstacles against which he

might perchance dash himself.

In silence and in that

calm night, the rider and the horse, covered with gleams of the moon, seemed

like dream visions. The Idumean stallion, dropping his ears and stretching his

neck, shot on like an arrow past the motionless cypresses and the white villas

hidden among them. The sound of hoofs on the stone flags roused dogs here and

there; these followed the strange vision with their barking; afterward, excited

by its suddenness, they fell to howling, and raised their jaws toward the moon.

The slaves hastening after Vinicius soon dropped behind, as their horses were

greatly inferior. When he had rushed like a storm through sleeping Laurentum,

he turned toward Ardea, in which, as in Aricia, Bovillæ, and Ustrinum, he had

kept relays of horses from the day of his coming to Antium, so as to pass in

the shortest time possible the interval between Rome and him. Remembering these

relays, he forced all the strength from his horse.

Beyond Ardea it seemed to

him that the sky on the northeast was covered with a rosy reflection. That

might be the dawn, for the hour was late, and in July daybreak came early. But

Vinicius could not keep down a cry of rage and despair, for it seemed to him

that that was the glare of the conflagration. He remembered the consul's words,

"The whole city is one sea of flame," and for a while he felt that

madness was threatening him really, for he had lost utterly all hope that he

could save Lygia, or even reach the city before it was turned into one heap of

ashes. His thoughts were quicker now than the rush of the stallion, they flew

on ahead like a flock of birds, black, monstrous, and rousing despair. He knew

not, it is true, in what part of the city the fire had begun; but he supposed

that the Trans-Tiber division, as it was packed with tenements, timber-yards,

storehouses, and wooden sheds serving as slave marts, might have become the

first food of the flames.

In Rome fires happened

frequently enough; during these fires, as frequently, deeds of violence and

robbery were committed, especially in the parts occupied by a needy and

half-barbarous population. What might happen, therefore, in a place like the

Trans-Tiber, which was the retreat of a rabble collected from all parts of the

earth? Here the thought of Ursus with his preterhuman power flashed into

Vinicius's head; but what could be done by a man, even were he a Titan, against

the destructive force of fire?

The fear of servile

rebellion was like a nightmare, which had stifled Rome for whole years. It was

said that hundreds of thousands of those people were thinking of the times of

Spartacus, and merely waiting for a favorable moment to seize arms against

their oppressors and Rome. Now the moment had come! Perhaps war and slaughter

were raging in the city together with fire. It was possible even that the

pretorians had hurled themselves on the city, and were slaughtering at command

of Cæsar.

And that moment the hair rose from terror on his head. He recalled all the conversations about burning cities, which for some time had been repeated at Cæsar's court with wonderful persistence; he recalled Cæsar's complaints that he was forced to describe a burning city without having seen a real fire; his contemptuous answer to Tigellinus, who offered to burn Antium or an artificial wooden city; finally, his complaints against Rome, and the pestilential alleys of the Subura. Yes; Cæsar has commanded the burning of the city! He alone could give such a command, as Tigellinus alone could accomplish it. But if Rome is burning at command of Cæsar, who can be sure that the population will not be slaughtered at his command also? The monster is capable even of such a deed. Conflagration, a servile revolt, and slaughter! What a horrible chaos, what a letting loose of destructive elements and popular frenzy! And in all this is Lygia.

A

second excerpt is Chilo and the Rabbis before Nero and Poppaea betraying the

Christians through lies. This is such

marvelous dialogue with Chilo unctuously flattering Caesar and his wife to be

on their good side.

"Do ye accuse the

Christians of burning Rome?" inquired Cæsar.

"We, lord, accuse

them of this alone,—that they are enemies of the law, of the human race, of

Rome, and of thee; that long since they have threatened the city and the world

with fire! The rest will be told thee by this man, whose lips are unstained by

a lie, for in his mother's veins flowed the blood of the chosen people."

Nero turned to Chilo:

"Who art thou?"

"One who honors

thee, O Cyrus; and, besides, a poor Stoic-"

"I hate the

Stoics," said Nero. "I hate Thrasea; I hate Musonius and Cornutus.

Their speech is repulsive to me; their contempt for art, their voluntary

squalor and filth."

"O lord, thy master

Seneca has one thousand tables of citrus wood. At thy wish I will have twice as

many. I am a Stoic from necessity. Dress my stoicism, O Radiant One, in a

garland of roses, put a pitcher of wine before it; it will sing Anacreon in

such strains as to deafen every Epicurean."

Nero, who was pleased by

the title "Radiant," smiled and said,-"Thou dost please

me."

"This man is worth

his weight in gold!" cried Tigellinus.

"Put thy liberality

with my weight," answered Chilo, "or the wind will blow my reward

away."

"He would not

outweigh Vitelius," put in Cæsar.

"Eheu! Silver-bowed,

my wit is not of lead."

"I see that thy

faith does not hinder thee from calling me a god."

"O Immortal! My

faith is in thee; the Christians blaspheme against that faith, and I hate

them."

"What dost thou know

of the Christians?"

"Wilt thou permit me

to weep, O divinity?"

"No," answered

Nero; "weeping annoys me."

"Thou art triply

right, for eyes that have seen thee should be free of tears forever. O lord,

defend me against my enemies."

"Speak of the

Christians," said Poppæa, with a shade of impatience.

"It will be at thy

command, O Isis," answered Chilo. "From youth I devoted myself to

philosophy, and sought truth. I sought it among the ancient divine sages, in

the Academy at Athens, and in the Serapeum at Alexandria. When I heard of the

Christians, I judged that they formed some new school in which I could find

certain kernels of truth; and to my misfortune I made their acquaintance. The

first Christian whom evil fate brought near me was one Glaucus, a physician of

Naples. From him I learned in time that they worship a certain Chrestos, who

promised to exterminate all people and destroy every city on earth, but to

spare them if they helped him to exterminate the children of Deucalion. For

this reason, O lady, they hate men, and poison fountains; for this reason in

their assemblies they shower curses on Rome, and on all temples in which our

gods are honored. Chrestos was crucified; but he promised that when Rome was

destroyed by fire, he would come again and give Christians dominion over the

world."

"People will

understand now why Rome was destroyed," interrupted Tigellinus.

"Many understand

that already, O lord, for I go about in the gardens, I go to the Campus

Martius, and teach. But if ye listen to the end, ye will know my reasons for

vengeance. Glaucus the physician did not reveal to me at first that their

religion taught hatred. On the contrary, he told me that Chrestos was a good

divinity, that the basis of their religion was love. My sensitive heart could

not resist such a truth; hence I took to loving Glaucus, I trusted him, I shared

every morsel of bread with him, every copper coin, and dost thou know, lady,

how he repaid me? On the road from Naples to Rome he thrust a knife into my

body, and my wife, the beautiful and youthful Berenice, he sold to a

slave-merchant. If Sophocles knew my history—but what do I say? One better than

Sophocles is listening."

"Poor man!"

said Poppæa.

"Whoso has seen the

face of Aphrodite is not poor, lady; and I see it at this moment. But then I

sought consolation in philosophy. When I came to Rome, I tried to meet

Christian elders to obtain justice against Glaucus. I thought that they would

force him to yield up my wife. I became acquainted with their chief priest; I

became acquainted with another, named Paul, who was in prison in this city, but

was liberated afterward; I became acquainted with the son of Zebedee, with

Linus and Clitus and many others. I know where they lived before the fire, I

know where they meet. I can point out one excavation in the Vatican Hill and a

cemetery beyond the Nomentan Gate, where they celebrate their shameless

ceremonies. I saw the Apostle Peter. I saw how Glaucus killed children, so that

the Apostle might have something to sprinkle on the heads of those present; and

I saw Lygia, the foster-child of Pomponia Græcina, who boasted that though

unable to bring the blood of an infant, she brought the death of an infant, for

she bewitched the little Augusta, thy daughter, O Cyrus, and thine, O

Isis!"

"Dost hear,

Cæsar?" asked Poppæa.

"Can that be!"

exclaimed Nero.

"I could forgive

wrongs done myself," continued Chilo, "but when I heard of yours, I

wanted to stab her. Unfortunately I was stopped by the noble Vinicius, who

loves her."

No comments:

Post a Comment