This is the sixth and final post on the second read of Sigrid Undset’s Catherine of Siena.

You can find Post #1 here.

Post #2 here.

Post #4 here.

Post #5 here.

Chapter

24

Catherine continuous her furious letter writing, this time to everyone and for all occasions, some to her personal friends and some for the cause of Pope Urban VI. In one letter to Raimondo she chastises him for being afraid of being killed on the road of a mission he backed out, and then in another letter she forgives him for his weakness. Her mother Lapa also joins Catherine in Rome.

Chapter

25

Undset narrates how the schism caused deep factions in Europe, where leaders and religious took sides. Eventually the schism turned violent as the King of France sent a military expedition to Italy, attacking some of the Italian cities and finally Rome. But the Pope’s army with its paid mercenaries overturned the French force, many thanking Catherine for the victory. Her letter writing continued strongly, even writing to Queen Joanna again, and this time it may have appeared Joanna changed her side to Urban, though she probably did it for Machiavellian reasons rather than what was right.

Chapter

26

As the year turned 1380, Catherine began to weaken as the Romans began to rebel against Pope Urban. By now she had become emaciated. Devils began to attack her both physically and spiritually. At times she could not walk; other times she struggled to walk to Mass and the Vatican. Sensing her life was waning, she wrote a letter to the Holy Father advising him how to comport himself in this struggle of the schism. She wrote a last letter to Raimondo telling him of her final spiritual struggles, and to take charge of her writings, and finally offering her life for the Church and glory of God.

Chapter

27

By the middle of Lent in 1380, Catherine was unable to leave her bed. By the Holy week her old confessor, Fra Bartolommeo Dominici, came to Rome and spent time with her. She made her confession and he celebrated Mass in her room. By April, Catherine had made her spiritual last will and testament, gathered all her sons and daughters, including her mother, and individually blessed them and gave them each final advice. She made a final open confession to them all, received absolution again, and on April 29th passed away while in prayer.

Chapter

28

At the hour of Catherine’s death, Raimondo recalls how he, leagues away in Genoa and not knowing she had passed, hearing her voice assuring his protection from heaven. Undset also delineates how a Roman woman, Semia on the day of Catherine’s death had a dream of Catherine being led into heaven by angels, and how Semia found out about Catherine’s body lying in protection at the basilica of Santa Maria sopra Minerva and paid her respects. Catherine was initially buried at the Basilica.

Chapter

29

Undset narrates how Catherine’s body was initially buried at the churchyard at Santa Maria sopra Minerva, then brought into the church itself where her head was cutoff and sent to Siena in a reliquary with her body entombed in the church and ultimately moved under the high altar. Undset briefly describes the fates of her closest sons and daughters. We learn of Catherine’s beatification and then canonization in 1461 by Pope Pius II.

###

My

Reply to Gerri:

Gerri wrote: "The

fasting and staying up all night? Checkmark for a manic state. The sense of

being tormented by demons/the devil - which Catherine regularly said she

suffered? Checkmark for the 13th century, when bipolar disorder was unknown and

a suffering person was believed to be possessed by the devil. And Catherine's

recurring illnesses that sent her to her bed - checkmark for the depressive

side of the illness.."

Very interesting Gerri. I could see some sort of compulsive disorder. Actually

it's likely, but she was never really depressed to be bi-polar. If you remember

she was always a happy upbeat person. But I do see some sort of high compulsive

inner drive that just won't stop. The exhaustion was because she just pushed

her self beyond her breaking point. Plus, she didn't eat. I would imagine there

was no fuel in the tank.

My

Reply to Gerri:

Gerri wrote: "Three

more things. You can tell I've become a Caterinati!"

Welcome to the club! Now you see how this book really alterted me. Because of

having read this book and falling in love with Catherine I ultimately became a

Lay Dominican, And if you're interested, my chosen religious name is Br. John

Catherine of Siena.

###

There

is an interesting passage in chapter 26 of St. Catherine and the ship that is

the church.

In the entrance to the

old basilica of St. Petyer’s, there was a mosaic of Giotto’s called

“Navicella”—St. Peter’s ship. Catherine

must have seen it hundreds of times, sometimes with deep thoughts, sometimes

without noticing it. But when she

received the vision which assured her that her heavenly Bridegroom had accepted

her prayer to sacrifice her life, the impression of this mosaic may have helped

to decide the pictorial form of her vision.

Sexagesima Sunday fell on

January 29. Catherine was on her knees

in St. Peter’s, where she had remained motionless for hours. But suddenly at vespers her friends saw that

she collapsed, as though an overwhelming burden had been laid on her shoulders

and crushed her body with its weight.

When they tried to help her to her feet she was so weak that she could

not stand. Supported by two of her sons

she was more carried than led home. When

they lifted her onto her bed it looked as though she were dying.

Tommaso Caffarini’s

description is repeated by William Flete:

As Catherine knelt at the tomb of St. Peter that Sunday at vespers,

while the winter evening began to creep in over the city, she felt how Jesus

Christ laid the whole weight of His Church, la

Navicella, on the thin shoulders of His faithful bride.

And the crushing pain was

sweet too—indescribably sweet. It meant

that He had accepted the sacrifice she had offered Him in love and desire. It meant too that He would soon come and lead

her from “this dark world” to the land of her desire and eternal union with

Him. (304-5)

I’m struck with how many contemporaneous writings about her took place and have survived. Raimondo, Fra Dominici, Cafferini come to mind. It helps that she was associated with Dominicans since they were the most educated order. I also want to point out that image of Giotto’s “Navicella.” It is an exquisite work of art. You can read about it here and if you click the picture you will get it in full screen and fully appreciate it.

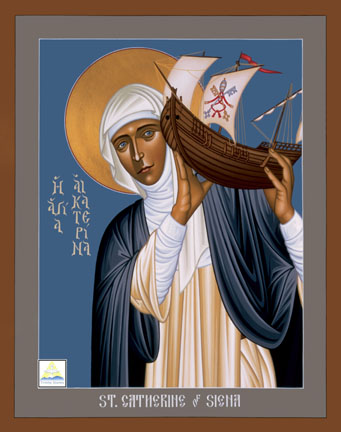

More importantly, Catherine takes the image and interprets it as her burden. The crushing weight of the ship—which stands for the church herself—becomes the means of her martyrdom. Undset goes on to describe Catherine’ last letter to Pope Urban, written just after this incident, even quoting extensively from it. I went and looked up that actual letter and found that Undset did not quote this particular sentence: “Comfort you, and do not fear on account of any bad reply which this rebel against your Holiness may have made or may make, for God will care for this and for everything else, as Ruler and Helper of the ship of Holy Church, and of your Holiness.” [Saint of Siena Catherine. Letters of Catherine Benincasa (Kindle Locations 3921-3923).] Notice she calls him “Ruler and Helper of the ship of Holy Church.” The ship is clearly on her mind. I also want to point out that sometimes you may see an image or icon of St. Catherine holding a ship. This is what the image is referring to, Catherine holding up the bark of Peter. Here is an example.

###

Some

of Catherine’s last words are interesting.

For instance, toward the end when her children are gathered round her

bed in sorrow, she says:

“And I promise you that I shall be with you always, and be of much more use to you on the other side than I ever could be here on earth, for then I shall have left the darkness behind me and move in the eternal light.” (p. 317)

The first part of that—“I shall be with you always”—is a quote right out of the Gospel of Matthew, the very last lines in fact. Jesus’ parting words are “And behold, I am with you always, until the end of the age” (Mat 28:20). So there she is quoting Jesus.

The next part is also a famous quote, that is, famous to the Order of Preachers. Catherine says “[I will] be of much more use to you on the other side than I ever could be here on earth.” Those words are very similar to that of St. Dominic himself, the founder of the order. On his death bed, he too had his close friars beside him in morning. The situation is exactly parallel to that of Catherine in this scene. St. Dominic’s words are, “Do not weep, my children; I shall be more useful to you where I am now going, than I have ever been in this life” (p. 225 from The Life of Saint Dominic, Augusta Theodosia Drane, 1988 by TAN Books, Charlotte, North Carolina, first published in 1857, London). Every Dominican knows those words of St. Dominic. It must have been on Catherine’s mind.

And the last part, “for then I shall have left the darkness behind me and move in the eternal light,” that movement from darkness to light is all over the Bible, but Catherine’s words seem to echo Jesus as He quotes Isaiah, “Land of Zebulun and land of Naphtali, the way to the sea, beyond the Jordan, Galilee of the Gentiles, the people who sit in darkness have seen a great light, on those dwelling in a land overshadowed by death light has arisen” (Mat 4:15-6). When you live in the words of God, you repeat the words of God, consciously or unconsciously.

Let’s

closely look at her moment of death as Undset depicts it.

Catherine continued to

pray till the last moment, for the Church, forPope Urban, for her children. She prayed with such intense love that her

disciples thought that not only their hearts, but the very stones must

break. “Beloved, You call me, I come. Not through any service of mine, but through

Your mercy and the power of Your blood…”

She made the sign of the cross and cried, “Blood, blood…” Then she bowed her head. “Father, into Your hands I commit my

spirit.” And as she said it, she gave up

the spirit. Her face had become as

beautiful as an angel’s, radiant with tenderness and happiness.

It was about the hour of terce on April 29, 1380. (320)

Terce, the Third Hour, is about 9 AM. Her last words of “Father, into Your hands I commit my spirit” is a little too neat. I personally don’t believe it. I’ve been reading I Am Going: Reflections on the Last Words of Saints by Mary Katherine Glavich, SND, and she lists “Blood, blood…” as Catherine’s last words. Her lifelong obsession with Christ’s blood makes that perfectly reasonable and fitting to be her last words. Those are the last words I consider she said.

###

I

was moved by Undset’s final words on Catherine.

It is certain that Catherine voluntarily—and few women have ever had such an inflexible will—chose to suffer ceaselessly for all she believed in, loved and desired: unity with God, the glory and honor of His name, His kingdom on earth, the eternal happiness of all mankind, and the re-birth of Christ’s Church to the beauty which it possesses when the radiance of its soul shines freely through its outward form—that form which was then stained and spoilt by its own degenerative servants and rebellious children. As Catherine expressed it: the strength and beauty of its mystical body can never diminish, for it is God; but the jewels with which its mystical body are adorned are the good accomplished by its sincere and faithful children.

Wow, what beautifully constructed sentences. And the imagery is wonderful too: the good works we do in our love of God are jewels that adorn His mystical body. Is the imagery Undset’s or is she paraphrasing it from Catherine? It sounds like one of those visual images St. Catherine would come up with.###

My Goodreads Review:

This is probably the best biography of a saint I have ever read, and no wonder. It’s written by Sigrid Undset, Nobel Prize winning author. Undset was a convert to Catholicism, and even became a Lay Dominican. Many of Undset’s novels are set in the Middle Ages, so it’s no surprise then she would write a biography of the most important Lay Dominican to have ever lived and one of the most influential women of the fourteenth century, St. Catherine of Siena. What is amazing about this biography is that though it has elements of a hagiography, it is detailed and reads like a work of realism. I’m even more impressed on my second read than after the first.

Why is the life of St. Catherine so engaging? St. Catherine of Siena incorporates into her

being every element of sainthood possible.

She lived a life of uncompromising holiness. You may be surprised to learn she was not a

consecrated religious, but a Third Order Dominican. Prayer was the foundation of her life, which

then led to an active ministry of taking care of the sick and the poor. She was a mystic who had who supernatural

experiences on an almost daily basis but was involved in the issues and

politics of her day. Though uneducated,

she learned Catholic theology so well she was correcting theologians, and she

went on to write—at some point she learned to read and write either mystically

or through perseverance—one of the great Catholic theological classics, her Dialogue. I marvel at her writings—mostly her

letters—for her intense prose and wonderful imagery. She was a natural poet. She was a little woman from a

non-aristocratic family who became so influential she was offering advice to

kings and queens, and her greatest accomplishment was in persuading Pope

Gregory XI to return the papacy to Rome after almost a century in Avignon. Her greatest disappointment was in not being

able to resolve the Papal Schism of 1378, and here too she offered her life up

in ascetic martyrdom in the hopes of a resolution. Because of her brilliance in articulating the

faith, in 1970, along with St. Teresa of Avila, she was recognized as a Doctor

of the Church, the first women. And

though her asceticism was severe, she was never dour. On the contrary she one of the most affable

and gregarious women of her time. She

attracted a large following known as the Caterinati.

Read this bio and perhaps you will be a Caterinati too!

No comments:

Post a Comment