I

was searching for a short story to break up a few of the reads I have going on,

and since this blizzard (which I posted on here) hit

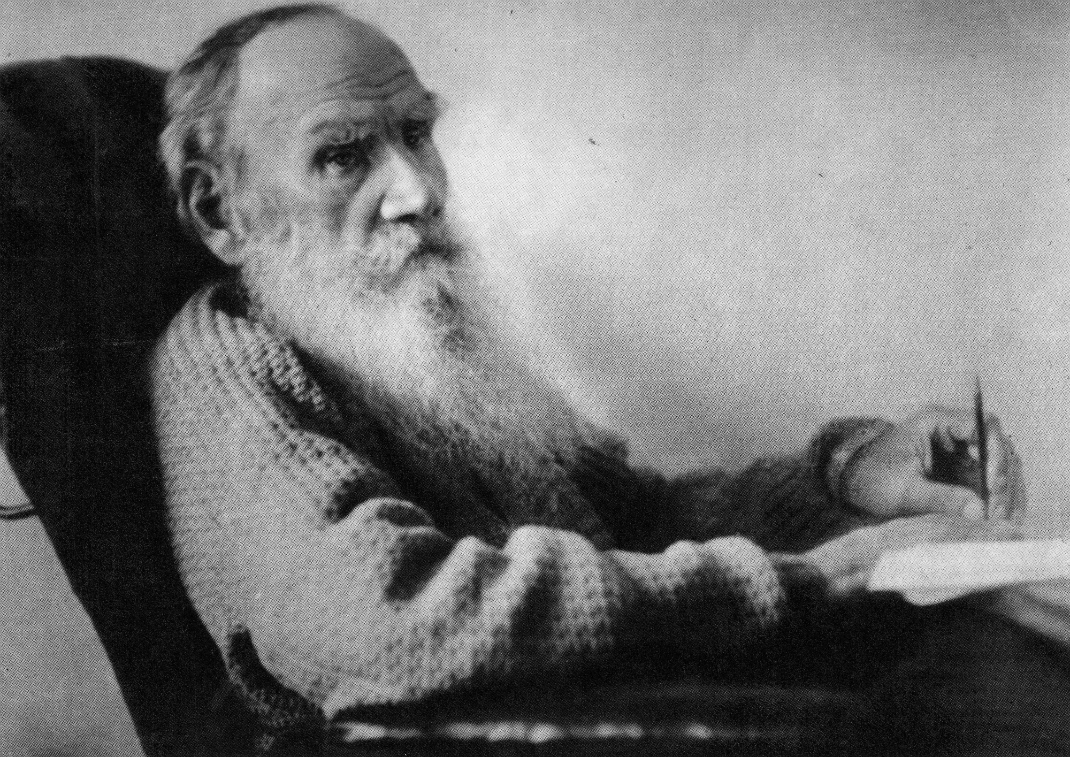

I longed for a story about winter and I recalled a famous Leo Tolstoy story

about two men being trapped in a blizzard.

Now I had read “Master and Man” many years ago—over twenty years, if not

thirty—and it has always stuck with me. It

really is a great short story. Actually

it’s on the longer side of a short story.

My edition ran for forty pages, which makes it close to a novella, and I

had remembered it as a short novel. But

Wikipedia, that ever pervasive corpus of knowledge, categorizes it as a short

story. I also noticed while reading the Wikipedia

entry that it was published in 1895, which makes it a relatively late story in

Tolstoy’s body of work, and squarely in his most religiously inspired works.

First

off, you can read it on line, and I believe this is the same translation I

read.

The

story is about a merchant who has this immediate opportunity to purchase a

grove at a bargain price, and goes off to complete the deal before someone else

takes it. Faced with impending bad weather, he brings along his servant. It’s winter and he misjudges the weather, and

they are caught in a blizzard, and it becomes a question of survival.

The

story is told in ten chapters, and I’m going to summarize it for you by

providing the kernel action of each chapter.

Here:

I. We are introduced to Vasili Andreevich, a

merchant and church elder, and his laborer, Nikita. Vasili has to go to purchase a grove at what

he sees as a huge bargain. It is very

cold and Vasili against his wishes takes Nikita with him.

II.

The depart and after a while with the wind blowing harder than they anticipated

and it starting to snow they realized for the first time they were lost.

III. They come upon a village and come across

three peasants, where they ask for directions and are pointed out. Suddenly they realize they are off the road

are now lost for the second time, and now a full blizzard is coming down.

IV. They come to another village and they stop at

a rich household where they warm up and are offered to spend the night. But Vasili afraid he will lose his bargain

insists that they can make it to their destination. One of the sons of the household sets out with

them as a guide.

V.

After the son leaves them at a turning point, the two continue but the blizzard

has so intensified that they can’t see a few feet in front. Shortly they are lost now for the third time,

and they just miss driving over a ravine.

The circle around but the horse has reached a point of exhaustion and

refuses to go on.

VI.

Nikita unharnesses the horse and decides to hunker down for the night. They try to sleep but Vasili unable and now

in a panic decides it’s best to search for a house rather than freeze to death. He mounts the horse and goes off into the

blizzard.

VII. Nikita, too tired to go with Vasili allows

sleep to overcome him, all with the thought that it will be his death.

VIII.

Vasili stumbles about in the blizzard, the horse escapes from under him, so

that now he is horseless and lost.

IX. In a panic he circles about and finds where

he started, the sled with Nikita. He

finds Nikita near death and he realizes it has all been his fault. This sting of conscience rises to an epiphany

of his inconsideration and selfishness and opens Nikita’s coat and his and

presses his body against Nikita’s to warm him.

In this position Vasili has a dream of someone calling him.

X.

In the morning we find that it is Nikita who is alive and Vasili who has

died. The peasants rescue Nikita.

The

story hinges on the term “master.” It is

set “in the seventies,” which means 1870s, and this is important given it was

published in 1895, a full twenty years after the setting. Tolstoy sets the story at a time when serfdom was abolished in Russia. From Wikipedia:

In 1861 Alexander II

freed all serfs in a major agrarian reform, stimulated in part by his view that

"it is better to liberate the peasants from above" than to wait until

they won their freedom by risings "from below".

Serfdom was abolished in

1861, but its abolition was achieved on terms not always favorable to the

peasants and served to increase revolutionary pressures. Between 1864 to 1871

serfdom was abolished in Georgia. In Kalmykia serfdom was only abolished in

1892.

Though

Nikita, the peasant, is no longer a serf, he has lived as a dependent serf for

most of his life. Not only is he

indebted to Vasili, but Nikita has a psychological and relational mentality of

a subordinate. But the relationship is

even more than that; it’s a class structure of lower rank. And with that comes a responsibility for

Vasili to protect and care for Nikita.

Now that the serfs are free, will Vasili still feel this obligation? To some degree he does. We learn in the first chapter that Vasili had

recently given Martha, Nikita’s wife, “wheat flour, tea, sugar, and a quart of

vodka, the lot costing three rubles, and also five rubles in cash, for which

she thanked him as for a special favour.”

There is an implied serf/master arrangement that has continued, of which

Vasili points out:

‘What agreement did we

ever draw up with you?' said Vasili Andreevich to Nikita. 'If you need

anything, take it; you will work it off. I'm not like others to keep you

waiting, and making up accounts and reckoning fines. We deal

straight-forwardly. You serve me and I don't neglect you.'

And when saying this

Vasili Andreevich was honestly convinced that he was Nikita's benefactor, and

he knew how to put it so plausibly that all those who depended on him for their

money, beginning with Nikita, confirmed him in the conviction that he was their

benefactor and did not overreach them.

'Yes, I understand,

Vasili Andreevich. You know that I serve you and take as much pains as I would

for my own father. I understand very well!' Nikita would reply. He was quite

aware that Vasili Andreevich was cheating him, but at the same time he felt

that it was useless to try to clear up his accounts with him or explain his

side of the matter, and that as long as he had nowhere to go he must accept

what he could get.

This

master and servant relationship cannot be minimized. “You serve me and I don’t neglect you,” Vasili

says. You know that I serve you.” It is critical to their relationship owing to

a feudal construct, and it points to a social hierarchy. Does Vasili really take care of Nikita? Yes, but he also cheats him.

This

hierarchy is further established in that Nikita is also a master, not of a

people but of the domestic animals. Also

from the first chapter we see Nikita hitching up the horse.

Now, having heard his

master's order to harness, he went as usual cheerfully and willingly to the

shed, stepping briskly and easily on his rather turned-in feet; took down from

a nail the heavy tasselled leather bridle, and jingling the rings of the bit

went to the closed stable where the horse he was to harness was standing by

himself.

'What, feeling lonely,

feeling lonely, little silly?' said Nikita in answer to the low whinny with

which he was greeted by the good-tempered, medium-sized bay stallion, with a

rather slanting crupper, who stood alone in the shed. 'Now then, now then,

there's time enough. Let me water you first,' he went on, speaking to the horse

just as to someone who understood the words he was using, and having whisked

the dusty, grooved back of the well-fed young stallion with the skirt of his

coat, he put a bridle on his handsome head, straightened his ears and forelock,

and having taken off his halter led him out to water.

Picking his way out of

the dung-strewn stable, Mukhorty frisked, and making play with his hind leg

pretended that he meant to kick Nikita, who was running at a trot beside him to

the pump.

'Now then, now then, you

rascal!' Nikita called out, well knowing how carefully Mukhorty threw out his

hind leg just to touch his greasy sheepskin coat but not to strike him--a trick

Nikita much appreciated.

After a drink of the cold

water the horse sighed, moving his strong wet lips, from the hairs of which

transparent drops fell into the trough; then standing still as if in thought,

he suddenly gave a loud snort.

'If you don't want any

more, you needn't. But don't go asking for any later,' said Nikita quite

seriously and fully explaining his conduct to Mukhorty. Then he ran back to the

shed pulling the playful young horse, who wanted to gambol all over the yard,

by the rein.

The

horse Mukhorty is there throughout the story as they lose their way through the

blizzard. Nikita is his master, also

with an obligation for his wellbeing. Notice

the contrast in personality. For Vasili

it is a social obligation, and only that.

There is no love or benevolence in it.

Nikita is tender and kind even to the domesticated beasts. He speaks to the horse as if they are

equals. Vasili on the other hand speaks

to Nikita in the language of exchange, of commerce. Vasili undergoes a dramatic realization that

Nikita is a man of equal standing before God at the story’s climax.

Stay

tune for the story’s dramatic conclusion in a Part 2 post.

One of the things I like about visiting your Blog, Manny, is that I learn about a lot of things without the need to read about them.

ReplyDeleteI can now add Leo Tolstoy's "Master and Man" to my collection of knowledge, and amaze people at parties about my education, thanx to Manny.

I once tried to read "War and Peace" but soon got tired, it was so big. Instead, I saw the film with subtitles on - so I can now claim that I read it.

God bless.

If you find Master and Man somewhere (or even off the internet) read it. I think you would like it. It's a whole lot shorter than War and Peace.

DeleteRussian writers are fun to read, and they all speak with the same voice. Even in children's stories. Waiting for part 2, even though I know what happens....

ReplyDeleteYes, they are fun to read. Especially the shorter works. I think Tolstoy is at his best in these short novels.

Delete