Happy

Mother’s Day! I know, that was two weeks

ago. So happy belated mother’s day. I meant to post something special for

Mother’s Day, as I usually do, but I didn’t realize it and posted on the word,

“scorbutic.” Scurvy

and Mother’s Day do not exactly go together, LOL.

But

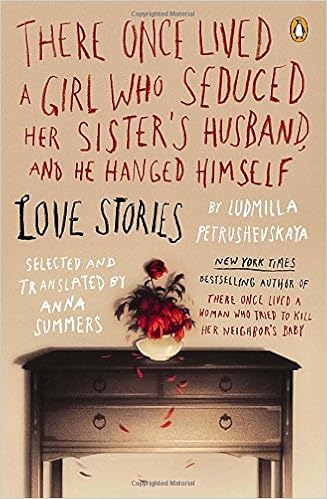

then I thought that a short story I recently read, : “Hallelujah, Family” by

Ludmilla Petrushevskaya would make a good post honoring motherhood. I have forgotten how I came across the

Russian author, Ludmilla Petrushevskaya.

Her name caught my eye somewhere, and so I

bought her collection of short stories with the intriguing tittle, There Once Lived A Girl Who Seduced

Her Sister’s Husband, And He Hanged Himself: Love Stories,

translated into English by Anna Summers.

Elissa Schappel in a NY Times book review of this collection points out

that the “Love Stories subtitle characterizes her a modern day Anton Checkov.

But

then I thought that a short story I recently read, : “Hallelujah, Family” by

Ludmilla Petrushevskaya would make a good post honoring motherhood. I have forgotten how I came across the

Russian author, Ludmilla Petrushevskaya.

Her name caught my eye somewhere, and so I

bought her collection of short stories with the intriguing tittle, There Once Lived A Girl Who Seduced

Her Sister’s Husband, And He Hanged Himself: Love Stories,

translated into English by Anna Summers.

Elissa Schappel in a NY Times book review of this collection points out

that the “Love Stories subtitle characterizes her a modern day Anton Checkov.

A few stories capture a

character in a Checkovian moment of clarity; some read like family lore,

recounted without fanfare or urgency; others echo the gossip women exchange

like currency. What is consistent is the

dark, fatalistic humor and bne-deep irony Petrushevskaya’s characters employ as

protection against the biting cold of loneliness and misfortune that seems

their birthright.

Ellen

Wernecke in this book review points out the “Love Stories” subtitle is

ironic.

The love affairs

Petrushevskaya depicts arrived soaked in the futility of the world where they

take place, with family and geography cuffing them even when the desire is

mutual. In “Young Berries,” the Grimm-est of the tales and a reminder of

Petrushevskaya’s breakout collection, a girl fielding a phone call from her

first crush is surrounded first by threatening classmates in a forest, and then

by her nosy relatives; unable to enjoy the moment, she makes her excuses and

hangs up. A grandmother’s cane watching over a woman who brings a man home in

“Two Deities” stands in for a lifetime of intrusion disguised as affection, and

during the tryst, Petrushevskaya writes, “the grandmother never left the room.”

The characters’ emotional lives mirror the Soviet-era privations under which

they live. Feeling is often their main extravagance, but it sometimes proves

too costly.

I’ve

only read this one story, but reading having read this story and having read

about the themes in the other stories through the reviews, it strikes me that

what is missing in these reviews is pointing out that at the heart of the

Petrushevskaya world is a breakdown in the family unit and a collapse in the

moral values that held the family together in the first place. I could not find the original published dates

of her stories, but she has been writing since the 1970s, which means she has

been writing in late Soviet Union, through the collapse of communism, and

through post-communist Russia. It would

not surprise many to see works documenting the dysfunctionality of family life

over those years in Russia.

There

is no story in the collection given the title that is the title of the collection. I looked specifically for it but I did find

that “Hallelujah, Family” was that story about a girl who seduces her

brother-in-law. This was story under a

different title.

Aesthetically

what caught my eye about this story was the style. This is the first story I have ever seen told

in bulleted, almost outline, form.

Here’s the beginning:

This, in short, is what

happened.

1. A young girl worked as

a secretary during the day and took classes at night. She came from a

respectable family, although her mother had a certain history:

2. She was the

illegitimate child of two mothers and one father—you see,

3. there were two

sisters: one was married, the other was just fifteen, and she got pregnant by

her brother-in-law, who hanged himself while she gave birth to a daughter she

hated.

4. That daughter grew up,

got married, and had a baby, a daughter.

5. That daughter was our

little secretary/student, Alla. Our Alla began to go out with men as soon as

she turned fifteen. Her mother cried and scolded her, but nothing helped, and

the mother began to lose her mind. In addition to which, she was diagnosed with

an illness

6. that promised

immobility. She and Alla got along horribly, because

7. Alla was raised by her

grandmother (3), who hated her daughter, Alla’s mother, and who, at

thirty-five, took her little granddaughter to live with her in a provincial

town where she shared a house with her uncle, a much older man.

8. Who knew what lay

behind the cohabitation of a fifty-year-old uncle and his niece, the only ones

left from a large family after all the wars, arrests, divorces, forced and

unforced deaths.

And

so the story goes on like this in numbered bullets, all the way to bullet

number 45, without any dramatization.

Between the bullets there is implied drama, very intense drama actually,

but no traditional narrative. Works of

art that deviate from an aesthetic norm need to justify the deviation,

otherwise it’s just a novelty. Is this

just a novelty or is there an aesthetic reason for the form?

What

the form made me do as a reader was to reconstruct the convoluted family tree

in a way that straight narrative would just tell. The bulleted items have a progression that is

not necessarily chronological, and so one has to piece together

relationships. Here is my

reconstruction: There is the 15 year old niece who gets pregnant by her

brother-in-law; the child’s name is Elena who had a child named Alla, the

central character of this story. Alla

goes on to have an illegitimate daughter of her own named Nadya. And so you have four generations of women

each linked through motherhood to the subsequent generation. The bulleted form focuses the reader’s

attention to tangled web of dysfunctionality.

What

the form made me do as a reader was to reconstruct the convoluted family tree

in a way that straight narrative would just tell. The bulleted items have a progression that is

not necessarily chronological, and so one has to piece together

relationships. Here is my

reconstruction: There is the 15 year old niece who gets pregnant by her

brother-in-law; the child’s name is Elena who had a child named Alla, the

central character of this story. Alla

goes on to have an illegitimate daughter of her own named Nadya. And so you have four generations of women

each linked through motherhood to the subsequent generation. The bulleted form focuses the reader’s

attention to tangled web of dysfunctionality.

But

I think even more important than forcing to the reader to focus on the

generational relationships, the bulleted form deconstructs in a clinical style

the lives of the characters to their bare dysfunctional selves. It’s clinical in the sense that it’s like a

psychological case study, and it brings the dysfunctionality to the foreground.

What

this story is ultimately about is family and the centrality of motherhood in

the family. It’s the relationship of the

mother to the child that shaped each dysfunctional family. We see this with Alla and her decision to

keep her baby after getting pregnant.

11. Then Alla, unmarried, gave birth. Her mother, stooped over, shuffled around,

washing diapers, cooking, cleaning. All

this she did grudgingly, as there was no money in the house. Elena lived on her invalid’s pension; her

husband had died, and Alla wasn’t working, having just given birth to a

daughter, Nadya. Elena’s memory of her

terrible past—of her illegitimate father’s death in the noose, of her quiet

teenage mother—weighed Elena down, and she nagged and nagged poor Alla, who’d

huddle by the baby’s crib and try not to cry.

12. Little Nadya had a

father, but he lived with Alla only sporadically, considering her used-up

material. He had made her pregnant

twice, and when it happened the third time, Victor—who saw himself not as a

future father but simply as facilitator of another abortion—put Alla in a cab

and directed the driver to the same hospital.

He told the driver to wait, walked Alla to the ward, and pecked her on

the cheek. This time, though, he left

before she changed into the sterile hospital robe, so he didn’t take her street

clothes from her.

13. Alla spent the night in the ward,

thinking—that she was twenty-five, that Victor had left her, that all her

future held were random liaisons with married men. As morning approached, Alla hugged her belly

and felt she had a family, that she was no longer alone.

The

child gives Alla incredible power, allowing her to reign in the wayward Victor,

with the help of Victor’s mother it should be noted. The woman gains power through motherhood,

while the child becomes a tool to acquire that power. It’s not the noblest of means, but the result

is family.

Some

questions come to mind as one contemplates the story. Was the series of the dysfunctional families

all rooted and caused from the initial girl who seduced her

brother-in-law? Or were the

dysfunctional families independently dysfunctional from values widespread in

the broken society at large? Perhaps

both is the answer. Will Victor settle

into his fatherly responsibilities or will he replicate a similar sort of

outcome as that brother-in-law who fornicated with his wife’s sister? The questions don’t get answered.

Now THIS looks a fun read! Thanks for the heads-up!

ReplyDelete